Concentrated Animal Feeding Operation: Difference between revisions

Florez4747 (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Florez4747 (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

<Blockquote>The numbers of animals in CAFOs differs widely, depending on the animal and regional permitting. CAFOs are categorized as small, medium, or large depending on the number and type of animal and the drainage system for their waste. Small CAFOs (those with small animal populations just under the definition of medium-sized) are often undercounted or un-permitted and are expanding in many regions where regulations apply only to larger facilities. By keeping animal operations to numbers that do not fall into the category for regulation, operators maintain more options—and more polluting options—for handling waste. Current permitting and legal differences between states makes it difficult to obtain an accurate count of the number of CAFOs in the US. Transparency of CAFO data, with respect to permit state, location, manure storage or type, and number of animals is low for almost every state; the US Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) does not have such data for about half of the CAFOs in its inventory of 2012. New algorithms are being applied to obtain better estimates and these approaches suggest that the number of CAFOs is actually more than 15% higher that which is routinely reported from manual enumerations.<Ref>Glibert, P.M. From hogs to HABs: impacts of industrial farming in the US on nitrogen and phosphorus and greenhouse gas pollution. Biogeochemistry 150, 139–180 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-020-00691-6</Ref></Blockquote> | <Blockquote>The numbers of animals in CAFOs differs widely, depending on the animal and regional permitting. CAFOs are categorized as small, medium, or large depending on the number and type of animal and the drainage system for their waste. Small CAFOs (those with small animal populations just under the definition of medium-sized) are often undercounted or un-permitted and are expanding in many regions where regulations apply only to larger facilities. By keeping animal operations to numbers that do not fall into the category for regulation, operators maintain more options—and more polluting options—for handling waste. Current permitting and legal differences between states makes it difficult to obtain an accurate count of the number of CAFOs in the US. Transparency of CAFO data, with respect to permit state, location, manure storage or type, and number of animals is low for almost every state; the US Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) does not have such data for about half of the CAFOs in its inventory of 2012. New algorithms are being applied to obtain better estimates and these approaches suggest that the number of CAFOs is actually more than 15% higher that which is routinely reported from manual enumerations.<Ref>Glibert, P.M. From hogs to HABs: impacts of industrial farming in the US on nitrogen and phosphorus and greenhouse gas pollution. Biogeochemistry 150, 139–180 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-020-00691-6</Ref></Blockquote> | ||

= Regulatory Loopholes = | = Regulatory Loopholes = | ||

Revision as of 22:26, 10 July 2023

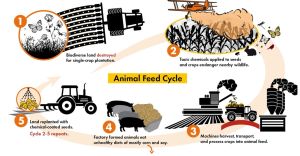

As a result of domestic and export market forces, technological changes, and industry adaptations, food animal production that was integrated with crop production has given way to fewer, larger farms that raise animals in confined situations. These large-scale animal production facilities are generally referred to as animal feeding operations. CAFOs are a subset of animal feeding operations and generally operate on a larger scale. While CAFOs may have improved the efficiency of the animal production industry, their increased size and the large amounts of manure they generate have resulted in concerns about the management of animal waste and the potential impacts this waste can have on environmental quality and public health.

Manure

Animal manure has long been a way to fertilize crops and restore nutrients to soil.

However, manure and wastewater from CAFOs affects water quality through surface runoff and erosion, direct discharges to surface water, spills and other dry-weather discharges, and leaching into the soil and groundwater. Excess nutrients in water can result in or contribute to low levels of oxygen in the water and toxic algae blooms, which can be harmful to aquatic life.

Improperly managed manure can also result in emissions to the air of particles and gases, such as methane, ammonia, hydrogen sulfide, and volatile organic compounds, which may also result in a number of potentially harmful environmental and human health effects.[1]

Water Pollution

Livestock and poultry create about 2.4 billion tons of manure a year.[2] Manure leads to nitrogen and phosphorus in water, which makes it harmful for people, potentially causing irritated skin and gastrointestinal and respiratory problems.[3]

Runoff

Excess manure is often times not able to be contained within the farms, which leads to runoff polluting water sources. Three quarters of factory farms discharge pollution.[4] Contamination of water from farms is not regulated under the 1972 Clean Water Act despite the large amount of contamination present in and around large factory farms. In 2022 the EPA was sued by dozens of advocacy groups over the lack of water protections.[5]

A report published by the 'Environmental Integrity Project'[6] in 2022 listed Indiana as the state with the most polluted water sources with 24,395 miles of rivers and streams listed as impaired for swimming in recreation. The second most polluted state was Oregon, with 17,619 miles of rivers and streams also classified unsafe for swimming/recreation. The third most polluted state was South Carolina, with 16,766 miles of polluted water. The pollution of these water sources is in part due to agricultural runoff.[7]

Extreme Weather

North Carolina

In 2016 Hurricane Matthew flooded at least 14 commercial-scale hog and poultry farms, and likely more smaller sized animal farms. This led to runoff and the waters were said to be tested for ammonia, nitrogen, phosphorus, and the fecal coliform present in hog waste. 1.7 million chickens. 112,000 Turkeys and 2,800 Swine were killed during Hurricane Matthew's rains.[8]

In 2018 Hurricane Florence flooded more than 100 manure lagoons on industrial hog farms in North Carolina.[9]

General Information

CAFOS are 'Confined Animal Feeding Operations' and have increased, in the US, by 10% between 2012 and 2020. Hog production increased by 13 percent during the same time frame. There are ~8.7 billion animals in CAFO operations - across the so-called United States - animals include: Cattle, Dairy Cows, Hogs, Broiler Chickens, and Turkeys. The areas where animals are farmed is concentrated regionally across the country.[11]

The waste from hog and dairy operations is mainly held in open lagoons that contribute to NH3 and greenhouse gas (as CH4 and N2O) emissions. Emissions of NH3 from animal waste in 2019 were estimated at > 4,500,000 MT. Emissions of CH4 from manure management increased 66% from 1990 to 2017 (that from dairy increased 134%, cattle 9.6%, hogs 29% and poultry 3%), while those of N2O increased 34% over the same time period (dairy 15%, cattle 46%, hogs 58%, and poultry 14%).[12]

The numbers of animals in CAFOs differs widely, depending on the animal and regional permitting. CAFOs are categorized as small, medium, or large depending on the number and type of animal and the drainage system for their waste. Small CAFOs (those with small animal populations just under the definition of medium-sized) are often undercounted or un-permitted and are expanding in many regions where regulations apply only to larger facilities. By keeping animal operations to numbers that do not fall into the category for regulation, operators maintain more options—and more polluting options—for handling waste. Current permitting and legal differences between states makes it difficult to obtain an accurate count of the number of CAFOs in the US. Transparency of CAFO data, with respect to permit state, location, manure storage or type, and number of animals is low for almost every state; the US Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) does not have such data for about half of the CAFOs in its inventory of 2012. New algorithms are being applied to obtain better estimates and these approaches suggest that the number of CAFOs is actually more than 15% higher that which is routinely reported from manual enumerations.[13]

Regulatory Loopholes

For decades, the EPA’s lax approach to factory farms has allowed the industry to freely pollute our waterways. The Clean Water Act clearly defines CAFOs as “point sources” of pollution. This should require them to follow discharge permits restricting their discharges into rivers and streams.

But due to the EPA’s weak regulations, only a small fraction of factory farms have the required permits. In fact, the agency itself estimates there are nearly 10,000 Large CAFOs nationwide illegally discharging without a Clean Water Act permit.

Even the permits that do exist are weak and don’t adequately protect water quality. For instance, these permits only limit nutrient and pathogen pollution, commonly associated with animal manure. But factory farm waste is not just manure; it contains many other pollutants of concern, such as antibiotics, artificial growth hormones, pesticides, and heavy metals.

Moreover, EPA allows CAFOs to dump huge quantities of untreated waste onto cropland — even when no crops are growing. This risks dangerous waste seeping into the soil and running off into streams.[14]

Sources

- ↑ "Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations: EPA Needs More Information and a Clearly Defined Strategy to Protect Air and Water Quality from Pollutants of Concern" (GAO-08-944) U.S. Government Accountability Office, September 2008 <https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-08-944>

- ↑ https://www.ars.usda.gov/research/publications/publication/?seqNo115=364421

- ↑ https://www.cdc.gov/healthywater/emergency/sanitation-wastewater/animal-feeding-operations.html

- ↑ https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2008/11/20/E8-26620/revised-national-pollutant-discharge-elimination-system-permit-regulation-and-effluent-limitations

- ↑ https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/oct/19/epa-lawsuit-water-pollution-factory-farms

- ↑ https://environmentalintegrity.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/CWA@50-report-EMBARGOED-3.17.22.pdf

- ↑ https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/oct/19/epa-lawsuit-water-pollution-factory-farms

- ↑ https://www.northcarolinahealthnews.org/2016/10/25/post-matthew-water-how-bad-is-it/

- ↑ https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/oct/19/epa-lawsuit-water-pollution-factory-farms

- ↑ https://reports.worldanimalprotection.org/US/Pesticides#5

- ↑ Glibert, P.M. From hogs to HABs: impacts of industrial farming in the US on nitrogen and phosphorus and greenhouse gas pollution. Biogeochemistry 150, 139–180 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-020-00691-6

- ↑ Glibert, P.M. From hogs to HABs: impacts of industrial farming in the US on nitrogen and phosphorus and greenhouse gas pollution. Biogeochemistry 150, 139–180 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-020-00691-6

- ↑ Glibert, P.M. From hogs to HABs: impacts of industrial farming in the US on nitrogen and phosphorus and greenhouse gas pollution. Biogeochemistry 150, 139–180 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-020-00691-6

- ↑ https://www.foodandwaterwatch.org/2022/11/03/epa-lawsuit-factory-farm-water-pollution/