Mycelium

Natural Intelligence

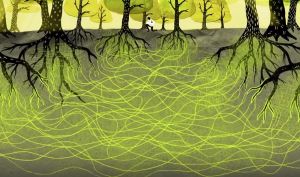

Understanding how mycelium works as an organism and the role it plays in our ecosystems has notably shaped how intelligence itself is defined.[1] As the neurological network of nature:

interlacing mosaics of mycelium infuse habitats with information-sharing membranes. These membranes are aware, react to change, and collectively have the long-term health of the host environment in mind. The mycelium stays in constant molecular communication with its environment, devising diverse enzymatic and chemical responses to complex challenges. [2]

The Mycelial archetype

Structures similar to Mycelium can be seen throughout Mother Earth and the universe. Some structures resembling Mycelial networks include patterns of hurricanes, dark matter and the internet, further Mycelial networks resemble patterns predicted by string theory. [3] **add photos of these examples**

Mycelium and the Environment

Habitats across the Earth depend upon Mycelium, a keystone species, to sustain themselves and their soils.[4] Mycelium hold soils together and help aerate them; Mycelium breaks down debris to build new blocks of soil after ecological catastrophes created by humans or otherwise. Mycelial networks partner with bacteria and other microorganisms to break down organic material creating stronger structures of soil. [5]

Mycelial Highways

Mycelium, specifically mycorrhizal fungi, partner with plants, microbes, and other animals below ground through its vast Mycelial network. Through this so called Mycelial Highway, chemicals released by one organism are able to quickly reach other organisms, increasing overall communication and resistance between all. Furthermore nutrients and water are transferred between Mycelial networks to deficient organisms.[6]

The mycelia of fungal species that form exterior sheaths around the roots of partner plants are termed ectomycorrhizal. The mycorrhizal fungi that invade the interior root cells of host plants are labeled endomycorrhizal... Both plant and mycorrhizae benefit from the association. Because ectomycorrhizal mycelium grows beyond the plant's roots, it brings distant nutrients and moisture to the host plant, extending the absorption zone well beyond the root structure. The mycelium dramatically increases the plant's ingestion of nutrients, nitrogenous compounds, and essential elements (phosphorus, copper, and zinc) as it decomposes surrounding debris... Plants with mycorhizal fungal partners can also resist diseases far better than those without. Fungi benefit from the relationship because it gives them access to plant-secreted sugars, mostly hexoses that the fungi convert to mannitols, arabitols, and erythritols. [7]

Mycelial networks are able to transport nutrients between different species of trees:

In one experiment, researchers compared the flow of nutrients via the mycelium between 3 trees: a Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), a paper birch (Betula papyrifera), and a western red cedar (Thuja plicata). The Douglas fir and paper birch shared the same ectomycorrhiza, while the cedar had an endomycorrhiza (VAM). The researchers covered the Douglas fir to simulate deep shade, thus lowering the tree's ability to photosynthesize sugars. In response, the mycorrhizae channeled sugars, tracked by radioactive carbon, from the root zone of the birch to the root zone of the fir. More than 9 percent of the net carbon compounds transferred to the fir orginiated from the birch's roots, while the cedar recieved only a smlla fraction. The amount of sugar transferred was directly proportional to the amount of shading. [8]

Mycorestoration

The science behind Mycelium as a mechanism for environmental restoration has not been researched in an extensive manner, likely because of Mycophobia, but this provides new possibilities of reversing the destructive effects of climate collapse.

Mycorestoration is the use of fungi to repair or restore the weakened immune systems of environments. Whether habitats have been damaged by human activity or natural disaster, saprophytic, endophytic, mycorrhizal, and in some cases parasitic fungi can aid recovery. As generations of mycelia cycle through a habitat, soil depth and moisture increase, enhancing the carrying capacity of the environment and the diversity of its members. [9]

Mycofiltration

Mycofiltration is the process of using Mycelium as a membrane to filter out microorganisms, pollutants, and silt.

Habitats infused with mycelium reduce downstream particulate flow, mitigate erosion, filter out bacteria and protozoa, and modulate water flow through the soil. More than a mile of threadlike mycelial cells can infuse a gram of soil. These fine filaments function as a cellular net that catches particles and, in some cases, digests them. as the substrate debris is digested, microcavities form and fill with air or water, providing buoyant, aerobic infrastructures with vast surface areas. Water runnoff, rich in organic debris, percolates through the cellular mesh and is cleansed. When water is not flowing, the mycelium channels moisture from afar through its advancing fingerlike cells. [10]

Paul Stamets created a method of utilizing Mycelium to filter downstream water flows/ other sources of water; Using the Mycelium to filter out disease, fecal matter, and other contaminates. The method involves inoculating wood chips or straw bales with Mycelium and placing them around water sources or downstream from contaminated water sources; Choosing best suited strains of mycelium, is necessary, to target specific pathogen carrying insects, like mosquitos, or other contaminates: Staph, coliform, and protozoa.

Factory Farms

Factory Farms produce mass animal waste in high concentrations and contain toxic organisms/ disease including Pfiesteria, Listeria, Streptococcus, Escherichia coli, amoebic parasites, and other viruses. [11] [12] A clear example of the threat factory farm waste production poses was when

hurricane Floyd hit North Carolina in 1999, the monsoon like rains caused dikes to burst and manure ponds to overflow, flooding thousands of acres with animal feces and causing incalculable health problems both on and off the farms. Residents in Charlotte were rudely awakened to the enormity of the problems by the fouling on their doorsteps. Filth filled the streets and flooded basements. The collateral damage included contaminated wells, fisheries, and crops. Many diseases spread, including ones pathologists are still at a loss to identify...[13]

Factory Farm waste production also pose risks to Indigenous communities. On the Santee Sioux Reservation cattle ranches produce waste, containing fecal coliform bacteria, which accumulate in septic ponds and leaches into the communities water source. The contaminates from the ranches have made the water undrinkable on the reservation. [14]

Mycelium offers unique solutions to water contamination:

A variety of forms of mycelial mats can prevent downstream pollution. I am keen on using bunker spawn-mycelium in burlap sacks- to build mycelial buffers to capture microbes and nutrients...[15]

Installing a Mycofilter

Paul Stamets explains how easily a mycofiltration system can be installed to help filter contaminates on farmland:

A gently sloped area below a feeding lot or manure pond, where effluent from the lot or pond continually seeps through, is an ideal site to install a mycofilter, essentially a myceliated organic drain field. For the bottom layer, scatter sawdust or wood chips to a depth of 3 to 4 inches. For the first of 2 layers of spawn, on top of the sawdust or wood chips, spread inoculated sawdust by hand or by silage spreader; use 1/4 pound inoculated sawdust per square foot of the site. Next, add a layer of corncobs 4 inches deep, and follow with a second layer of spawn. because high winds and harsh sun can dry out mycofiltration beds, cover the site with waste cardboard before adding the last layer of straw. The finish layer of straw should be 4 to 6 inches deep to provide shade, aeration, and moisture to layers below. (If natural rains do not provide sufficient moisture, sprinklers can be set up for the first few weeks until the site becomes charged with mycelia.) The surface area of the mycofilter should be at least several times larger than the surface area of the manure pond of feeding lot, depending upon depths, slope, and flows.

Mycofilters are best built in the early spring. Once established, the mycofilter will mature in a few months and remain viable for years, provided that fresh organic debris is periodically added to the top layer and covered with more straw. For some, the best time for this may be after the fall harvests, when agricultural debris is plentiful. After some time, red worms will arrive and transform the mycelium, cardboard, and debris into rich soil. every 2 to 3 years, the newly emerging material can be scooped up using a front loader tractor and used elsewhere as soil; the timing of this cycle will vary. (Incidentally, gourmet mushrooms may form after rains depending upon temperatures. These mushrooms "reseed" the beds, provided there is enough food.)...

... I encourage farmers to try this method. The amount of time to install a mycofilter is minimal, only a couple hours. Spawn will probably be your biggest expense, but once established and cared for, the mycelium can regenerate itself until the debris base has been reduced to soil. As these areas mature, they usually become covered with native grasses, which also play remediative roles. A universe of compatible organisms shares this habitat, with mushroom mycelia reigning as the pioneering organisms.[16]

Burlap Bunker Spawn

Mycoforestry

Mycoforestry is the use of fungi/mycelium to sustain forest communities; The potential benefits include: preservation of native forests, recovery and recycling of woodland debris, enhancement of replanted trees, strengthening sustainability of ecosystems, and economic diversity.[17] The timber industry poses a serious risk to old growth forests and other forests in general:

With each generation of trees we cut, soils increasingly shallow and we further jeopardize the health of forests. The richness and depth of soil is our legacy from centuries of mycelial activity. And with each harvesting and replanting, the soil loses nutrients and gradually becomes overtaxed, no longer able to support the growth of healthy trees. Trees prematurely climax, falling over as the root wads can't hold the trees upright. Current "sustainable" logging practices strive to balance the impact of over harvesting with ecological restoration, potentially irreconcilable objectives. The bottom line is that we need to focus on carbon cycles and raise the nutritional plateau in timberlands by accelerating decomposition of wood debris and restarting plant cycles.[18]

When forests are clear cut the mycorrhizal fungal communities die back and decomposition of the left over debris slows down, which in turn hinders habitat recovery. Making clear cut debris fields more mycelial friendly helps speed up and balance the decomposition cycle; Making the fields more mycelial friendly involves bringing saprophytic and other fungi into close contact with the debris. The size of forest debris affects the inoculation rate of mycelium, Paul Stamets suggests:

... creating a matrix by chipping wood into variably sized fragments in order to let mycelium quickly grab and invade the wood. Wood fragments with greater surface areas are more likely to have contact with spores or mycelium; this is especially true in the cultivation of mushrooms, where spawn growth is integral to success. The fungal recycling of wood chips lessens reliance on fertilizers, herbicides, and pesticides. So leaving the chips in the woods helps recovering forest soils just like leaving stubble on farmed land helps agricultural soil.[19]

Mycoremediation

Mycoremediation is the use of fungi to degrade or remove toxins from the environment.

Mycoremediation practices involve mixing mycelium into contaminated soil, placing mycelial mats over toxic sites, or a combination of these techniques, in onetime or successive treatments[20]

Mycelium acts as a catalyst for other animals, bacteria and plants to populate sites of contamination to break down toxic chemicals and contaminates.

The powerful enzymes secreted by certain fungi digest lignin and cellulose, the primary structural components of wood. These digestive enzymes can also break down a surprisingly wide range of toxins that have chemical bonds like those in wood... These complex mixtures allow the mycelium to dismantle some of the most resistant materials made by humans or nature. Since many of the bonds that hold plant material together are similar to the bonds found in petroleum products, including diesel, oil, and many herbicides and pesticides, mycelial enzymes are well suited for decomposing a wide spectrum of durable toxic chemicals. Because the mycelium breaks the hydrogen-carbon bonds, the primary nonsolid byproducts are liberated in the form of water and carbon dioxide. More than 50 percent of the organic mass cleaves off as carbon dioxide and 10 to 20 percent as water; this is why compost piles dramatically shrink and ooze leachate and they mature.[21]

Oil Spills

Mycopesticdes

No Till Farming

Industrial till-based farming requires a massive input of fertilizers, pesticides, and insecticides. Dr. Vandana Shiva comments on the inefficency of these inputs and outputs:

Industrial agriculture is an inefficient and wasteful system which is chemical intensive, fossil fuel intensive and capital intensive. It destroys nature’s capital on the one hand and society’s capital on the other, by displacing small farms and destroying health. It uses 10 units of energy as input to produce one unit of energy as food. This waste is amplified by anther factor of ten when animals are put in factory farms and fed grain, instead of grass in free range ecological systems, Rob Johnston celebrates these animal prisons as efficient, ignoring the fact that it takes 7 kg of grain to produce one kg of beef, 4kg of grain to produce 1 kg of pork and 2.4 kg of grain to produce 1 kg of chicken... [22]

Mycelium in conjunction with organic no till farming reduces the input of artificial fertilizers and pesticides/insecticides, while increasing the overall productivity of farmland. Additionally, no till farming involving mycelium increases drought resistance, builds healthy diversely populated soils, aerates soils, and makes soils/crops more resistant to extreme temperatures and disease. Furthermore, no till farming practices decrease organic carbon release by 41 percent versus tilling soils. [23] [24]

Indigenous Uses

Mycophobia

The fear of mycelium (typically implicit) as usually manifested through a fear of their fruiting bodies (mushrooms) is known as mycophobia.

Pyrolize

"This Underground Economy Exists in a Secret Fungi Kingdom" (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WWD_1Nq6iwQ)

"Fungal Banking with Biochar and Hugelkultur" (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EoKS07Y1ASk)

"The Organic Internet of a Mycelium Network: Suzanne Simard, Paul Stamets, and Terence Mackenna" (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rGyECGJqWDU)

Cited

- ↑ https://microdose-journey.com/mycelium-networks/

- ↑ Mycelium Running, by Paul Stamets

- ↑ Paul Stamets, Mycelium Running, Page 9

- ↑ https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-019-43980-3

- ↑ Paul Stamets, Mycelium Running, Page 11

- ↑ https://www.cell.com/trends/plant-science/fulltext/S1360-1385(12)00133-1?_returnURL=https%3A%2F%2Flinkinghub.elsevier.com%2Fretrieve%2Fpii%2FS1360138512001331%3Fshowall%3Dtrue

- ↑ Paul Stamets, Mycelium Running, Page 24

- ↑ Paul Stamets, Mycelium Running, Page 24-26

- ↑ Paul Stamets, Mycelium Running, Page 55

- ↑ Paul Stamets, Mycelium Running, Page 58

- ↑ Paul Stamets, Mycelium Running, Page 63

- ↑ https://branchoutnow.org/coronavirus-and-the-climate-a-singular-crisis/

- ↑ Paul Stamets, Mycelium Running, Page 63-64

- ↑ https://branchoutnow.org/growing-sovereignty-part-2-regenerating-sacred-water/

- ↑ Paul Stamets, Mycelium Running, Page 64

- ↑ Paul Stamets, Mycelium Running, Page 68

- ↑ Paul Stamets, Mycelium Running, Page 69

- ↑ Paul Stamets, Mycelium Running, Page 72

- ↑ Paul Stamets, Mycelium Running, Page 73

- ↑ Paul Stamets, Mycelium Running, Page 86

- ↑ Paul Stamets, Mycelium Running, Page 87-88

- ↑ https://wilderutopia.com/health/vandana-shiva-industrial-agriculture-destroys-life/

- ↑ Paul Stamets, Mycelium Running, Page 65-66

- ↑ https://www.usda.gov/media/blog/2017/11/30/saving-money-time-and-soil-economics-no-till-farming