Biochar: Difference between revisions

| Line 97: | Line 97: | ||

To transform feedstocks into biochar, in any form, means applying a great deal of heat while limiting exposure to oxygen. | To transform feedstocks into biochar, in any form, means applying a great deal of heat while limiting exposure to oxygen. | ||

Fire will reduce biomass to ash in the presence of oxygen. This is the common phenomenon | Fire will reduce biomass to ash in the presence of oxygen. This is the common phenomenon known as combustion. Deprived of air, however, the thermal decomposition process - less a burn than a smolder - separates biomass into gases, liquids, oxygenated compounds (e.g., wood vinegar), and solid (biochar). The ratio between these components, given a particular feedstock, will depend on the conditions of its heating. Generally speaking, lower temperatures will yield more char, while higher ones yield liquids and oils potentially useful as [[biofuel]]. | ||

[https://s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/wp2.cahnrs.wsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/32/2021/11/Biomass2Biochar-Chapter11.pdf] | [https://s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/wp2.cahnrs.wsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/32/2021/11/Biomass2Biochar-Chapter11.pdf] | ||

Revision as of 22:03, 25 April 2022

OVERVIEW COPY TEXT

Definition

Historical

Origins

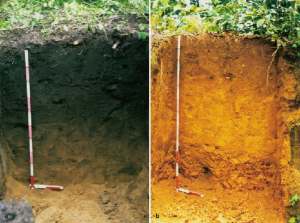

For most of the last 9000+ years, many Indigenous Peoples in the Amazon Rainforest enriched the forest soil surrounding their villages using biochar.[3] In a compost mix with other amendments, the use of biochar by Indigenous farmers created highly fertile and nutrient-rich soils known as yana allpa (Quechuan: "black earth"), more widely known by the Spanish term "terra preta" today.[4]

Yana allpa is visibly distinctive via the noticeable presence of black carbon in the form of biochar, which exists in concentrations around 70 times greater than surrounding soils.[5] Its high nutrient profile, cation exchange capacity, and more balanced pH also stands in sharp contrast to oxisol, the less fertile and highly acidic yellow soils which grow throughout most of the Amazon.

The disruption of Indigenous biochar cultivation and yana allpa generation by the onset of European colonization severely fragmented and destroyed Indigenous knowledges regarding these practices. As a result, much of what is known about yana allpa today is the result of archaeology:

1. Fieldwork has shown that yana allpa sites are widely distributed across the region and most likely to be near the Amazon River. They have persisted in their fertility and distinctiveness for thousands of years.[6] The longevity of yana allpa is a core body of evidence empirically demonstrating biochar's long-term carbon sequestration abilities.

2. Yana allpa sites, now largely overgrown, once had fewer towering trees, but were heavily populated by numerous shorter fruit trees. Yana allpa is so closely associated with evidence of concentrated human residence - such as handmade ceramics and the remains of fortified villages - that archaeologists were forced to revise upwards their estimates of pre-colonial Native populations by millions of more people.[7] The existence of large villages and cities in the Amazon which had been attested to by early reports, but subsequently dismissed following their destruction amid the genocidal violence of European colonization, has consequently been supported by this evidence.[8]

Revival

Technical

Biochar is an output of pyrolysis. Biomass - the feedstock which fuels pyrolysis - usually yields carbon in this highly compressed solid form. However, the value of the char comes not only from what it contains, but also from what it does not (yet) contain. That is, the porous structure of its carbon content makes biochar act like a microscopic sponge. [9] Accordingly, the following two sections map the positive and negative spaces of biochar in more detail.

Crystals

Biochar is the most stable form of organic carbon known to exist in the terrestrial environment.[10] This is due to the fact that it is a crystalline solid with a high degree of orderliness in its molecules. The biochar process (burning within a low-oxygen environment) results in the formation of carbon-carbon bonds that do not easily break. These bonds give biochar its stability and - being structured like graphite rather than diamond - its black color[11][12]. Biochar's high stability means that it will not decompose in soils and therefore can serve as a long-term (1000+ year) storehouse for carbon.[13]

Cavities

While the stability of biochar is an important attribute, it is the porosity of biochar that gives it many of its unique properties. The pores in biochar can be classified as either micropores (<2 nm in diameter), mesopores (2-50 nm), or macropores (>50 nm).[14] Being highly porous, Biochar has a high surface area to volume ratio (upwards of 340 m2/g). [15] This gives biochar a large internal surface on which various chemical and biological processes can take place. For instance, biochar's porosity allows it to act as a sponge for water and nutrients, while serving as a substrate for the growth of microorganisms.

ADSORB vs ABSORB:

Production

Feedstocks

Any biomass can - theoretically - become biochar. The most famous example, charcoal, simply refers to biochar for which wood is the feedstock. There are at least as many different feedstocks as there are flora.

Biomass waste materials appropriate for biochar production include wild detritus, crop residues (both field residues and processing residues such as nut shells, fruit pits, bagasse, etc) and animal manures, as well as yard and food wastes. [16]

The following sections organize this plentiful array of resources according to their location in wild, rural and urban ecologies, respectively.

<<Forest / Plains>>

- Hardwoods

- Alder - Balsa - Beech - Hickory - Mahogany - Maple - Oak - Teak - Walnut

Hardwood biochar has X

- Softwoods

- Cedar - Fir - Douglas fir - Juniper - Pine - Redwood - Spruce - Yew

Softwood biochar is Y

- Grasses

- Switchgrass - Bamboo - Ditch Weed

Grassy biochar tends to Z . best prepared in such n such

<<Farm / Pasture>>

- Crop residues

- Straw - Corn - Rice

- Animal manures

- Chicken - Swine

<<Municipal / Industry>>

- Yard waste

- Grass Clippings - Sticks or Twigs - Woodchips - Sawdust

- Food waste

- Fruits

- Biosolids

- Paper - Pulps - Sewage sludge - Digested sludge

Projects

Processes

To transform feedstocks into biochar, in any form, means applying a great deal of heat while limiting exposure to oxygen.

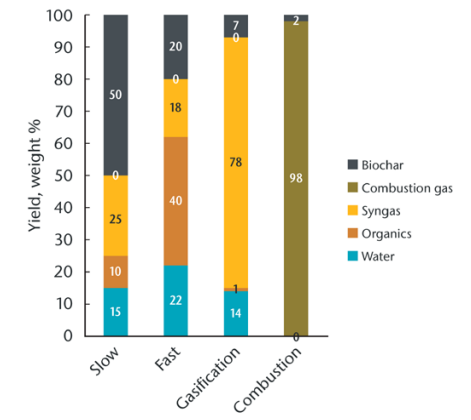

Fire will reduce biomass to ash in the presence of oxygen. This is the common phenomenon known as combustion. Deprived of air, however, the thermal decomposition process - less a burn than a smolder - separates biomass into gases, liquids, oxygenated compounds (e.g., wood vinegar), and solid (biochar). The ratio between these components, given a particular feedstock, will depend on the conditions of its heating. Generally speaking, lower temperatures will yield more char, while higher ones yield liquids and oils potentially useful as biofuel.

(Bullets from Table 6 - yield refers to biochar: [18])

Torrefaction

- 200-300 °C

- 10-60 minutes

- 75-90 % yield

Slow Pyrolysis

- 350-900 °C

- minutes to days

- 25-35 % yield

Fast Pyrolysis

- 500-700 °C

- 0.5-10 seconds

- 12-15 % yield

Gasification

- 700-900 °C

- seconds to hours

- 5-10 % yield

Projects

Application

Carbon Sequestration

Biochar has been identified as a key means of sequestering (removing and storing) carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, either into the Earth's soil or products made from Biochar. A group of scientists published in Nature in 2019 identified Biochar as the negative emissions technology "at the highest technology readiness level." [20] According to their research, the global carbon sequestration potential of biochar (when also using potassium as a low-concentration additive) is over 2.6 billion tons of CO2/year.

Projects

Soil Amendment

Biochar increases long-term soil organic carbon content in a form which can endure for thousands of years, as seen in the Amazonian Black Earth.

Additional benefits of Biochar for soil include improved soil texture, nutrient retention, cation exchange capacity,[2] water retention,[3] and microorganism habitat.[4]

Projects

Feed Additive

Livestock farmers increasingly use biochar as a regular feed supplement to improve animal health and increase nutrient intake efficiency. As biochar gets enriched with nitrogen-rich organic compounds during the digestion process, the excreted biochar-manure becomes a more valuable organic fertilizer causing lower nutrient losses and greenhouse gas emissions during storage and soil application.

An analysis of 112 scientific papers on biochar feed supplements has shown that in most studies and for all farm animal species, positive effects could be found on different parameters, such as:

- growth

- digestion

- feed efficiency

- toxin adsorption

- blood levels

- meat quality

- gas emissions

However, a relevant part of the studies obtained results that were not statistically significant. Most importantly, no significant negative effects on animal health were found in any of the reviewed publications. [21]

Projects

Water Filter

Charcoal has been a part of water treatment for at least 4000 years.[22] Biochar’s incredible porosity and surface area give it a high capacity to adsorb a wide variety of contaminants from water.[23]

Laboratory testing shows that biochar can effectively reduce contaminants including:

- Heavy metals like lead, copper, zinc, cadmium, cobalt, and nickel;

- Organics such as gasoline compounds and other volatile organics, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB), polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAH), and some herbicides, pesticides and pharmaceuticals;

- Chemical oxygen demand (COD) and biological oxygen demand (BOD);

- Nutrients such as phosphorus and ammonia;

- Totals suspended solids (TSS).[24]

A 2019 study found that using biochar in modified sand filters for wastewater treatment would be just as effective as other methods in removing microbes while significantly reducing the amount of land needed, a major obstacle to wastewater treatment on small farms.[25]

How To

Video: https://youtu.be/kazEAzGWuIc

Manual: http://www.aqsolutions.org/images/2010/06/water-system-handbook.pdf

Projects

Insulation

Asphalt

Ink

Paper

Plastic

Supercapacitor

The fabrication of biochar-based materials with excellent electrochemical behavior as a "supercapacitor" can be sustainable and low cost.[26]

These capacitors are endowed with excellent reliability, high power density, and fast charging/discharging characteristics. Supercapacitors are thus utilized in a wide range of applications, particularly in electrical vehicles.

Biochar has been established a potent material of interest for electrochemical energy storage and conversion in this way. However, research needs to be carried out in resolving a few outstanding issues. For large scale and cost-effective deployment, the conversion efficiency and quality of biomass into biochar are required to be maintained without additional steps for treatments, while biochar functionalization (i.e. surface oxidation, amination, sulfonation etc.) should avoid intricate operations and toxic chemicals to retain a green solution. [27]

Sources

[1] <https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-019-41953-0>

[2] <https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/11/11/3211/pdf>

[3] <https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2015.00733/full>