Free Breakfast For Children: Difference between revisions

| (71 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

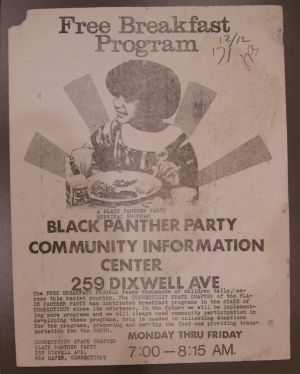

[[File:BreakfastProgramFlyer.jpg||thumb|right|Free Breakfast Program flyer, 1968]] | [[File:BreakfastProgramFlyer.jpg||thumb|right|Free Breakfast Program flyer, 1968]] | ||

[[Huey P. Newton]] and Bobby Seale founded the [[Black Panther Party]] for self-defense in 1966 in Oakland, California. The organization would grow and open branches across the so called United States. They would begin their free breakfast for children program in January, 1969, at Father Earl A. Neil’s St. Augustine Episcopal Church in Oakland, California, feeding 11 children the first day and growing to 135 children by the end of the week.<Ref>https://www.aaihs.org/the-black-panther-party/</Ref> Less than two months later a second location for feeding children would open in San Francisco at Sacred Heart Church. As the Black Panther Party proliferated across the country they made the free breakfast program a mandatory staple of each branch. At its | [[Huey P. Newton]] and Bobby Seale founded the [[Black Panther Party]] for self-defense in 1966 in Oakland, California. The organization would grow and open branches across the so called United States. They would begin their free breakfast for children program in January, 1969, at Father Earl A. Neil’s St. Augustine Episcopal Church in Oakland, California, feeding 11 children the first day and growing to 135 children by the end of the week.<Ref>https://www.aaihs.org/the-black-panther-party/</Ref> Less than two months later a second location for feeding children would open in San Francisco at Sacred Heart Church. As the Black Panther Party proliferated across the country they made the free breakfast program a mandatory staple of each branch. At its | ||

peak, approximately forty-five chapters across the country participated in the Breakfast Program, feeding thousands of children every day.<ref>https://www.history.com/news/free-school-breakfast-black-panther-party</ref> | peak, approximately forty-five chapters across the country participated in the Breakfast Program, feeding thousands of children every day.<ref>https://www.history.com/news/free-school-breakfast-black-panther-party</ref> While many of the men in the party receive credit for the Breakfast Program, Women and Mothers were crucial to the implementation and execution of the program.<Ref>Nik Heynen (2009) Bending the Bars of Empire from Every Ghetto for Survival: The Black Panther Party's Radical Antihunger Politics of Social Reproduction and Scale, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 99:2, 406-422, DOI: 10.1080/00045600802683767</Ref> | ||

The free breakfast program was a response to the United States federal government's [[War on Poverty]], which was supposed to be providing food, housing, and safety to impoverished people across the country. The Black Panther party felt as though the so called [[War on Poverty]] was not taking care of the Black Community, so they chose to take matters into their own hands. <ref>https://www.eater.com/2016/2/16/11002842/free-breakfast-schools-black-panthers</ref> The free breakfast program was one of the many Black Panther Party [[Survival Programs]], which included education programs, health clinics, shoe giveaways, clothing giveaways, and prison busing program, which helped bring family members to prisons to visit their loved ones, sickle cell anemia testing (they tested over half a million people,) and a free ambulance service in Winston Salem, North Carolina; All of the Black Panther Party survival programs were free, and were all pieces of the party's goals of Black self-determination, and liberation from the constraints of [[capitalism]] and the legacies of slavery. <Ref>https://www.pbs.org/hueypnewton/actions/actions_survival.html</Ref> | The free breakfast program was a response to the United States federal government's [[War on Poverty]], which was supposed to be providing food, housing, and safety to impoverished people across the country. The Black Panther party felt as though the so called [[War on Poverty]] was not taking care of the Black Community, so they chose to take matters into their own hands. <ref>https://www.eater.com/2016/2/16/11002842/free-breakfast-schools-black-panthers</ref> The free breakfast program was one of the many Black Panther Party [[Survival Programs]], which included education programs, health clinics, shoe giveaways, clothing giveaways, and prison busing program, which helped bring family members to prisons to visit their loved ones, sickle cell anemia testing (they tested over half a million people,) and a free ambulance service in Winston Salem, North Carolina; All of the Black Panther Party survival programs were free, and were all pieces of the party's goals of Black self-determination, and liberation from the constraints of [[capitalism]] and the legacies of slavery. <Ref>https://www.pbs.org/hueypnewton/actions/actions_survival.html</Ref> | ||

= Food Sovereignty = | = Food Sovereignty & Environmental Justice = | ||

The Black Panther Party's ten point platform in conjunction with their [[Survival Programs]] directly combated capitalism, settler colonialism, and police brutality.<Ref>https://www.historyisaweapon.com/defcon1/fhamptonspeech.html</Ref> This fact is made clear by point number one of the Party's ten point platform: "We Want Freedom. We Want Power to Determine the Destiny of Our Black Community. We believe that Black people will not be free until we are able to determine our destiny," and point number ten: "We Want Land, Bread, Housing, Education, Clothing, Justice And Peace."<Ref>https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/primary-documents-african-american-history/black-panther-party-ten-point-program-1966/</Ref> <br><br> | |||

The Black Panther Party combated these institutions of oppression, in-part by creating alternative mutual-aid structures<Ref>https://libcom.org/article/huey-newton-introduces-revolutionary-intercommunalism-boston-college-november-18-1970</Ref> to acquire sustenance, education, healthcare etc, which help begin/ continue movements aimed towards Black, Latnix, & Indigenous self-determination/sovereignty.<Ref>https://emorywheel.com/the-black-panthers-and-young-lords-how-todays-mutual-aid-strategies-took-shape/</Ref> Furthermore, these programs help create a framework of environmental justice vis a vis sovereignty, localized self-determination, and mutual aid: | |||

<blockquote> ... the BPP’s campaigns against police brutality are, in my view, clearly within the broader ambit of environmental justice. I would argue | |||

that the BPP’s work to provide free health care and health information to marginalized communities was also EJ-related activism for the same reason—it was about countering the effects of racist state and institutional violence and the long-term effects of racism and environmental racism that results in higher rates of hypertension, asthma, lead poisoning, and other illnesses. Moreover, the Free Breakfast for Children Program can be firmly placed within a long history of food justice movements, a social formation that a number of scholars have argued is firmly within the realm of environmental justice (Alkon and Agyeman 2011)..<Ref>https://www.gejp.es.ucsb.edu/sites/secure.lsit.ucsb.edu.envs.d7_gejp-2/files/sitefiles/publication/PEJP%20Annual%20Report%202018.pdf#page=11</Ref> </Blockquote> | |||

By exposing the glaring contradictions within society, where the state and corporations control who is able to acquire basic healthy food,<Ref>https://truthout.org/articles/capitalist-economies-overproduce-food-but-people-cant-afford-to-buy-it/</Ref> clean water,<Ref>https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/apr/28/indigenous-americans-drinking-water-navajo-nation and shelter,</Ref> the Black Panther Party drew connections between capitalism, police brutality, and [[Food Sovereignty]]. These connections were apparent when the Black Panther Party established solidarity with the [[United Farm Workers]] led by [[Cesar Chavez]].<Ref>Araiza, Lauren. “‘In Common Struggle against a Common Oppression’: The United Farm Workers and the Black Panther Party, 1968-1973.” The Journal of African American History, vol. 94, no. 2, 2009, pp. 200–23. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25610076. Accessed 10 Jan. 2023.</Ref> The United Farm Workers was a union made to organize primarily Mexican American farm workers to combat Low wages, unfair hiring practices, and dangerous working conditions. In 1969 the UFW began a boycott against Safeway, the largest purchaser of California grapes behind the Department of Defense at the time, because Safeway had refused to stop purchasing grapes from farms the UFW was also striking against for unfair pay and harsh conditions. During both of these strikes the Black Panther Party published support for the strikes in their weekly party newspaper, distributed nationally and internationally. In addition to supporting the strike the paper also emphasized that Safeway had never donated to the Free Breakfast Program. <blockquote>The Black Panther Party's boycott of Safeway stores was a tremendous contribution to the UFW's boycott efforts. When the Panthers set up pickets at Safeway stores, they were an intimidating sight with their black leather jackets, berets, and dark glasses. UFW organizer Gilbert Padilla recalled that when he organized the grape boycott in the Los Angeles area, Panthers on the picket line acted as a restraint on police harassment because the Panthers "scared the hell out of them." More importantly, the party's boycott of Safeway was well organized and innovative. Bobby Seale, like many other Panthers, had served in the military, and drawing on his experience in the U.S. Air Force, Seale created a "motor pool" for party use that was employed in the Safeway boycott. In the evenings when people went shopping for groceries, party members would not only explain to them why they should be boycotting Safeway, but they also provided transportation to the Lucky's grocery stores, which had donated to the Free Breakfast for Children Program and had agreed not to sell California grapes.<Ref>Araiza, Lauren. “‘In Common Struggle against a Common Oppression’: The United Farm Workers and the Black Panther Party, 1968-1973.” The Journal of African American History, vol. 94, no. 2, 2009, pp. 200–23. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25610076. Accessed 10 Jan. 2023.</Ref></Blockquote> | |||

The Black Panther Party's support of the UFW strike and their motor pool forced the Safeway store located at 27th and West streets in Oakland to close. Declaring solidarity with the UFW and materially supporting the strike clearly established connections between varying races in relation to [[Food Sovereignty]], fair treatment of workers, fair pay, police brutality, and capitalism. Beyond these connections this solidarity illustrated the power communities have in supporting one another independent of capitalism. <br><br> | |||

Through the pursuit of [[Food Sovereignty]] and the party's ten point platform a clear connection can be made to environmental justice through the right to healthy food and clean drinking water. Minority communities are far more likely<Ref>https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/news/press-releases/racial-ethnic-minorities-low-income-groups-u-s-air-pollution/</Ref> to be exposed to environmental harms across the so called united states and across the world; Environmental harms caused by capitalism and its inherent environment destroying extraction and pollution. [[Food Sovereignty]] and environmental justice both require the right to self-determination free from capitalist exploitation and environmental destruction.<Ref>https://therednation.org/revolutionary-socialism-is-the-primary-political-ideology-of-the-red-nation-2/</Ref> | |||

= Party Branches = | = Party Branches = | ||

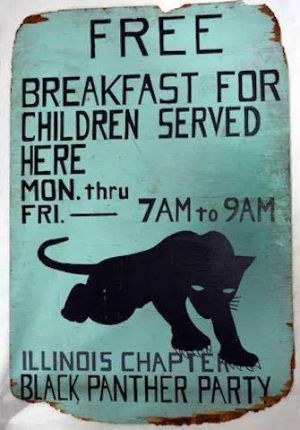

[[File:BreakfastFlyer.jpg||thumb|right|Illinois Free Breakfast Program flyer]] | |||

== Oakland and San Francisco == | == Oakland and San Francisco == | ||

The free breakfast programs in Oakland and later San Francisco garnered support from people from various walks of life and resulted in many donations to the program and general support from moderate white people. | The free breakfast programs in Oakland and later San Francisco garnered support from people from various walks of life and resulted in many donations to the program and general support from moderate white people. FBI Director Hoover, in a memo to a San Francisco surveillance officer in 1969, stated <blockquote>One of our primary aims in counterintelligence as it concerns the [Black Panther Party] is to keep this group isolated from the moderate black and white community which may support it ... ... This is most emphatically pointed out in their Breakfast for Children Program, where they are actively soliciting and receiving support from uninformed whites and moderate blacks.<ref>https://www.eater.com/2016/2/16/11002842/free-breakfast-schools-black-panthers</ref></blockquote> | ||

== Chicago == | == Chicago == | ||

[[File:FredHampton.jpeg||thumb|right|Fred Hampton talking to children during a free breakfast program feeding. Credit: Chicago Sun-Times collection, Chicago History Museum]] | [[File:FredHampton.jpeg||thumb|right|Fred Hampton talking to children during a free breakfast program feeding. Credit: Chicago Sun-Times collection, Chicago History Museum]] | ||

[[Fred Hampton]], chairman of the Chicago Branch of the [[Black Panther Party]] gave a speech on April, 29th, 1969 explaining the connections between capitalism and young Black children not having food to eat. He explained the steps the Free Breakfast Program were taking to eradicate the hunger prevalent throughout their communities and across the country.<Ref> Nik Heynen (2009) Bending the Bars of Empire from Every Ghetto for Survival: The Black Panther Party's Radical Antihunger Politics of Social Reproduction and Scale, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 99:2, 406-422, DOI: 10.1080/00045600802683767 </Ref> Hampton stated:<blockquote> Our Breakfast for Children program is feeding a lot of children and the people understand our Breakfast for Children program. We sayin’ something like this—we saying that theory’s cool, but theory with no practice ain’t shit. You got to have both of them—the two go together. We have a theory about feeding kids free. What’d we do? We put it into practice. That’s how people learn. A lot of people don’t know how serious the thing is. They think the children we feed ain’t really hungry. I don’t know five year old kids that can act well, but I know that if they not hungry we sure got some actors. We got five year old actors that could take the academy award. Last week they had a whole week dedicated to the hungry in Chicago. Talking ’bout the starvation rate here that went up 15%. Over here where everybody should be eating. Why? Because of capitalism. <Ref>https://www.marxists.org/archive/hampton/1969/04/27.htm</Ref></blockquote> About a month after this speech a memo Signed by FBI director [[J. Edgar Hoover]], conveyed how the FBI viewed the free breakfast program as a threat to national security: <blockquote>You state that the bureau should not attack programs of community interest such as the BPP “Breakfast for Children Program.” . . . You have obviously missed the point. The BPP is not engaged in the program for humanitarian reasons. This program was formed by the BPP . . . to create an image of civility, assume community control of Negroes, and fill adolescent children with their insidious poison.<Ref> Nik Heynen (2009) Bending the Bars of Empire from Every Ghetto for Survival: The Black Panther Party's Radical Antihunger Politics of Social Reproduction and Scale, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 99:2, 406-422, DOI: 10.1080/00045600802683767 </Ref></Blockquote> A former Black Panther Party member spoke on the Chicago police department attempting to disrupt the food program, <blockquote>It was a lot of organizing because of course we had to go out and find people to give us food for the program and all that. . . . Anyways, the night before it [the first breakfast program in Chicago] was supposed to open, the Chicago police broke into the church where we had the food and mashed up all the food and urinated on it. So we had to | |||

delay the opening. But what that caused was just all kinds of attention, and people were just lining up to give us donations.<Ref> Nik Heynen (2009) Bending the Bars of Empire from Every Ghetto for Survival: The Black Panther Party's Radical Antihunger Politics of Social Reproduction and Scale, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 99:2, 406-422, DOI: 10.1080/00045600802683767 </Ref></Blockquote> | |||

On December 4th 1969 the Chicago police department in coordination with the FBI kicked down the doors of the apartment where Fred Hampton and his pregnant girlfriend were sleeping. They shot and killed Mark Clark, who was on guard at the time. As Mark Clark was dying he fired one shot at the police, and this was the only shot fired from the Black Panther Party, while police fired fully automatic weapons at the apartment. One of the bullets hit Fred Hampton in the shoulder, and he was then killed, while asleep, after officers entered his bedroom and shot him point blank in the head, assassinating him; Hampton's girlfriend survived. Hampton was asleep during the assassination, because an FBI informant drugged him with secobarbital.<Ref>↑ Nik Heynen (2009) Bending the Bars of Empire from Every Ghetto for Survival: The Black Panther Party's Radical Antihunger Politics of Social Reproduction and Scale, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 99:2, 406-422, DOI: 10.1080/00045600802683767 </Ref> <br> <br> <blockquote> The attention the murder of Hampton and Clark brought, especially because of Hampton’s visibility around the Breakfast Program, helped to marshal increased grassroots support among African American radicals but also liberal whites. The program became a vehicle, therefore, not only for providing sustenance to children but also as a cause around which to organize the space of the black community in particularly scaled ways.<Ref> Nik Heynen (2009) Bending the Bars of Empire from Every Ghetto for Survival: The Black Panther Party's Radical Antihunger Politics of Social Reproduction and Scale, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 99:2, 406-422, DOI: 10.1080/00045600802683767</Ref></blockquote> | |||

== Los Angeles == | == Los Angeles == | ||

In Los Angeles Flores Forbes spoke to community members about how the breakfast program would help children “grow and intellectually develop because children can’t learn on empty stomachs.” The breakfast program fed around 1,200 children a week in Los Angeles. <Ref>https://www.aaihs.org/the-black-panther-party/</Ref> | |||

On December, 8th, 1969 the first SWAT raid to be conducted in the so called United States was undertaken at the Los Angeles Branch Head Quarters of the Black Panther Party. More than 350 police officers were involved in the raid to allegedly execute arrest warrants; There were 13 Black Panther members in the building including three women and five teenagers. The LAPD would detonate explosives on the roof of the headquarters and call in a tank for reinforcements during the raid. Bernard Arafat, a Black Panther Party member, <blockquote> awoke to explosions rocking the library of the Black Panthers’ 41st and Central Avenue headquarters in Los Angeles. Above him, footsteps stomped across the roof. Then gunfire erupted. | |||

Arafat wasn’t a seasoned Panther. He was a 17-year-old runaway from juvenile hall whose parents had both died when he was 13. After years of committing small-time crimes, Arafat was taken in by the Panthers and gained a sense of purpose. He helped with the organization’s breakfast program, feeding hungry kids on their way to school.<Ref>https://www.latimes.com/opinion/story/2019-12-08/50-years-swat-black-panthers-militarized-policinglos-angeles</Ref></blockquote> | |||

According to the [[Los Angeles Police Department]] the Special Weapons Assault Team (SWAT,) was originally created so the police force could respond to sniper and hostage situations, like situations that allegedly occurred during the [[Watts Rebellion]], but the occurrence of these events were rare (less than 5% of SWAT raids are for the original mission of the unit across the country today,<Ref>https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.1805161115</Ref>) so the SWAT unit had never been deployed prior to the raid on the Black Panther Party's headquarters. <blockquote>In its Panther deployment, SWAT was transformed from a tool of surgical precision into a blunt-force battering ram, and that’s ultimately how it would find its calling in police departments across the country — especially in African American communities.<Ref>https://www.latimes.com/opinion/story/2019-12-08/50-years-swat-black-panthers-militarized-policinglos-angeles</Ref></blockquote> | |||

The raid resulted in <blockquote>13 arrests and a total of 72 criminal counts being filed. But at trial, the Panthers’ attorneys, including a young Johnnie Cochran, argued that the group had acted in self-defense. SWAT had entered the building unannounced with guns blazing. | |||

A mixed-race jury agreed, finding the Panther defendants not guilty on almost all charges, including the most serious ones of assault with a deadly weapon and conspiracy to murder policemen. Arafat, who had skipped bail and fled underground to Puerto Rico, returned to Los Angeles.<Ref>https://www.latimes.com/opinion/story/2019-12-08/50-years-swat-black-panthers-militarized-policinglos-angeles</Ref></Blockquote> | |||

== Houston == | |||

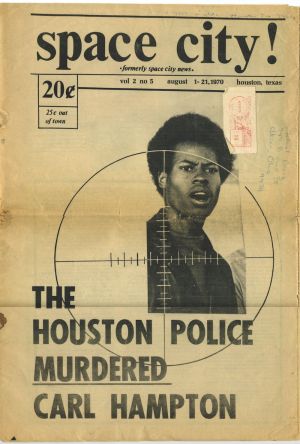

[[File:CarlHampton.jpg||thumb|right|]] | |||

<Blockquote>... On July 26 of [1970], [[Carl Hampton]] spoke to a crowd of about one hundred people. Although only twenty-one years old, Hampton had emerged as an important political force in the city's Black community. After a sojourn in Oakland, California, where he witnessed the Black Panther Party's efforts to "serve the people" through free breakfast programs for children and through patrols that monitored and challenged police misconduct, Hampton started the [[People's Party 2]] in Houston. He directed the group's efforts to feed and clothe poor people in the Third Ward from the party's headquarters in the 2800 block of Dowling... The material deprivation of Black people loomed large in shaping Hampton's politics. "If black people did not live in substandard housing, poor conditions, or suffer all the other unequal indignities," he declared, "there would be no [[People's Party 2]].<Ref>Ruth Thompson-Miller, How Racism Takes Place By George Lipsitz Temple University Press. 2008. 310 pages. $27.95, Social Forces, Volume 93, Issue 4, June 2015, Page 149, https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sot021</Ref></Blockquote> | |||

== New York == | == New York == | ||

| Line 25: | Line 56: | ||

= Legacy of Free Breakfast Program = | = Legacy of Free Breakfast Program = | ||

== Oakland Community | == Peoples Kitchen Collective == | ||

== | The legacy of the Black Panther Party and their survival programs, including the free breakfast program, lives on in Oakland and beyond. One organization that was inspired by the Black Panther Party's Free Breakfast program is the Peoples Kitchen Collective in West Oakland and according to their website they cook: <blockquote> a Free Breakfast each year at the Life is Living festival in West Oakland. Since 2011, we have served over 7,000 breakfasts made from donations by local food businesses and urban farms. The menu has included creamy grits, collard greens, tofu or egg scramble, and sweet potato biscuits. It is a meal made with love, by community for community, so that all of us can survive together in the face of rampant white supremacy and gentrification. This a meal to feed hope and fuel the resistance. We have looked to these resources -- foundations, archives, libraries, and bookstores, to learn about the powerful history on whose shoulders we stand. These projects and organizations are continuing the legacy of the Panthers in the Bay Area and beyond.<Ref>http://peopleskitchencollective.com/panthers-legacy</Ref></Blockquote> A former Black Panther, Billy X Jennings, who serves as an archivist was a part of the original Free Breakfast Program. <Ref>https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/oct/17/black-panther-party-oakland-free-breakfast-50th-anniversary</Ref> | ||

== Planting Justice == | |||

According to their website: "Since 2009 Planting Justice has built over 550 edible permaculture gardens in the San Francisco Bay Area, worked with five high-schools to develop food justice curricula and created over 40 green jobs in the food justice movement for people transitioning from prison." Their tenets include: [[Food Sovereignty]], Economic Justice, and Community Healing.<Ref>https://plantingjustice.org/about/</Ref> <br><br> | |||

The impact the Black Panther Party had on the Planting Justice program is evident: "The Black Panther Party’s 10 point program is a valuable tool for teaching liberation education. It not only gives students a deeper understanding of the civil rights movement, it further provides a container for participants to connect this history to their individual experience and discuss the most pressing issues in their community. Participants learn about the alliances built between the Black Panther Party and the United Farm Workers during their grape boycott and everyone gets to enjoy a fruit salad made with produce grown on local unionized organic farms."<Ref>https://plantingjustice.org/black-panther-party-10-point-program/</Ref> <br><br> | |||

Furthermore, on a blog post on their website Haleh Zandi explains the importance of alliance building in the context of white supremacy and [[Food Sovereignty]]: <blockquote>Alliance building is, in fact, a necessary means for achieving social change towards justice and human rights, and within the food justice movement in the United States, addressing white, middle-class privilege is one of the keys to building alliances between grassroots organizations working for sovereignty over affordable, nutritious food sources. Failure to confront social and cultural differences within liberal social movements and the ways in which the community food movement reproduces white privilege undermines the efforts of social change (Slocum 2006). As evidenced above, racism is an organizing process in the industrialized and globalized food system: people of color disproportionately experience food insecurity, lose their farms, and face the dangerous work of food processing and agricultural labor. Between 1990 and 1998, the total number of young Indigenous Americans who deal with diabetes increased by 71% (Acton et al 2002), and Indigenous Americans are 2.6 times more likely than European Americans to have diabetes, which has a direct correlation with one’s diet. Likewise, African American and Latino American households experienced food insecurity at double the national average in 2003 (Weil 2004; or see Shields 1995). Indeed, the United States’ food system was built upon a foundation of genocide, slavery, and racist institutions which have dispossessed racialized groups of cultural pride, land use, and the right to a dignified livelihood through the overlapping dynamics of race, class, and gender disparities.<Ref>https://plantingjustice.org/planting-justice/resources-food-justice-research-racial-equality/</Ref></Blockquote> | |||

== Food Justice Movement == | |||

A major legacy of the Free Breakfast Program is the [[food justice]] movement it helped catalyze. The Party played a leading role in approaching food through a revolutionary lens, inspiring numerous food-related initiatives “used as a tool to develop a set of community-based solutions that might help transform the very political and economic systems that had historically oppressed low-income and ethnic minority communities.”<ref>https://timeline.com/the-black-panthers-helped-free-breakfast-programs-9e4756d93510</ref> | |||

This reflected the view of David Hillard, former Chief of Staff of the Black Panther Party, that "we’ve always been involved in food, because food is a very basic necessity, and it’s the stuff that revolutions are made of."<ref>Garrett Broad, "More than Just Food: Food Justice and Community Change"</ref> | |||

== USDA School Breakfast Program == | |||

By 1969, the success of the program had become a matter of federal policy debate, with the National School Lunch Program administrator admitting in a 1969 U.S. senate hearing that the Panthers were feeding more poor school children than the State of California.<ref>https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/black-panther-partys-free-breakfast-program-1969-1980/</ref> | |||

According to History.com: | |||

<blockquote> The public visibility of the Panthers’ breakfast programs put pressure on political leaders to feed children before school. The result of thousands of American children becoming accustomed to free breakfast, former party member Norma Amour Mtume told Eater, was the government expanded its own school food programs. | |||

Though the [[USDA]] had piloted free breakfast efforts since the mid 1960s, the program only took off in the early 1970s—right around the time the Black Panthers’ programs were dismantled. In 1975, the School Breakfast Program was permanently authorized.<ref>https://www.history.com/news/free-school-breakfast-black-panther-party</ref></blockquote> | |||

In response: | |||

<blockquote>The BPP saw such actions as an unfair co-option on the part of establishment actors who looked to minimize the BPP’s importance and to move the control of community program development and management away from low-income Black communities themselves. Such co-option represented another factor that led to the slow demise of the BPP’s influence in communities across the nation.<ref>Garrett Broad, "More than Just Food: Food Justice and Community Change"</ref></blockquote> | |||

< | It was not until a new set of waivers were established in 2020 in response to the [[COVID-19 pandemic]] that a complicated and often stigmatizing bureaucratic application process was eliminated, and free lunches were provided for all students. Before this new expansion, as many as 75% of U.S. school districts had unpaid "student meal debt."<ref>https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/jun/04/us-school-hunger-crisis-federal-waivers-end</ref> After the federal breakfast programs were established, noticeable improvements in students' levels of focus, energy, and reduced stress were observed by teachers, while schools no longer had to deal with unnecessary paperwork.<ref>https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/free-school-lunches-are-ending-house-passes-deal-summer-meals-child-nu-rcna34745</ref> | ||

This expansion proved short-lived. In 2022, federal school meal programs faced a "perfect storm" according to Diane Pratt-Heavner, spokesperson for the School Nutrition Association.<ref>https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/free-school-lunches-set-end-creating-perfect-storm-high-inflation-rcna33688</ref>. Even though a poll in 2021 found that "74% of Americans support making universal free school meals permanent nationwide," the Democratic Party's surrender to Republican opposition led to the expiration of this highly popular policy, once again excluding tens of millions of students from receiving free meals.<ref>https://melmagazine.com/en-us/story/black-panthers-free-breakfast-program</ref><ref>https://www.npr.org/2022/10/26/1129939058/end-of-nationwide-federal-free-lunch-program-has-some-states-scrambling</ref> | |||

= Sources = | = Sources = | ||

Latest revision as of 18:41, 24 June 2023

Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale founded the Black Panther Party for self-defense in 1966 in Oakland, California. The organization would grow and open branches across the so called United States. They would begin their free breakfast for children program in January, 1969, at Father Earl A. Neil’s St. Augustine Episcopal Church in Oakland, California, feeding 11 children the first day and growing to 135 children by the end of the week.[1] Less than two months later a second location for feeding children would open in San Francisco at Sacred Heart Church. As the Black Panther Party proliferated across the country they made the free breakfast program a mandatory staple of each branch. At its peak, approximately forty-five chapters across the country participated in the Breakfast Program, feeding thousands of children every day.[2] While many of the men in the party receive credit for the Breakfast Program, Women and Mothers were crucial to the implementation and execution of the program.[3]

The free breakfast program was a response to the United States federal government's War on Poverty, which was supposed to be providing food, housing, and safety to impoverished people across the country. The Black Panther party felt as though the so called War on Poverty was not taking care of the Black Community, so they chose to take matters into their own hands. [4] The free breakfast program was one of the many Black Panther Party Survival Programs, which included education programs, health clinics, shoe giveaways, clothing giveaways, and prison busing program, which helped bring family members to prisons to visit their loved ones, sickle cell anemia testing (they tested over half a million people,) and a free ambulance service in Winston Salem, North Carolina; All of the Black Panther Party survival programs were free, and were all pieces of the party's goals of Black self-determination, and liberation from the constraints of capitalism and the legacies of slavery. [5]

Food Sovereignty & Environmental Justice

The Black Panther Party's ten point platform in conjunction with their Survival Programs directly combated capitalism, settler colonialism, and police brutality.[6] This fact is made clear by point number one of the Party's ten point platform: "We Want Freedom. We Want Power to Determine the Destiny of Our Black Community. We believe that Black people will not be free until we are able to determine our destiny," and point number ten: "We Want Land, Bread, Housing, Education, Clothing, Justice And Peace."[7]

The Black Panther Party combated these institutions of oppression, in-part by creating alternative mutual-aid structures[8] to acquire sustenance, education, healthcare etc, which help begin/ continue movements aimed towards Black, Latnix, & Indigenous self-determination/sovereignty.[9] Furthermore, these programs help create a framework of environmental justice vis a vis sovereignty, localized self-determination, and mutual aid:

... the BPP’s campaigns against police brutality are, in my view, clearly within the broader ambit of environmental justice. I would argue that the BPP’s work to provide free health care and health information to marginalized communities was also EJ-related activism for the same reason—it was about countering the effects of racist state and institutional violence and the long-term effects of racism and environmental racism that results in higher rates of hypertension, asthma, lead poisoning, and other illnesses. Moreover, the Free Breakfast for Children Program can be firmly placed within a long history of food justice movements, a social formation that a number of scholars have argued is firmly within the realm of environmental justice (Alkon and Agyeman 2011)..[10]

By exposing the glaring contradictions within society, where the state and corporations control who is able to acquire basic healthy food,[11] clean water,[12] the Black Panther Party drew connections between capitalism, police brutality, and Food Sovereignty. These connections were apparent when the Black Panther Party established solidarity with the United Farm Workers led by Cesar Chavez.[13] The United Farm Workers was a union made to organize primarily Mexican American farm workers to combat Low wages, unfair hiring practices, and dangerous working conditions. In 1969 the UFW began a boycott against Safeway, the largest purchaser of California grapes behind the Department of Defense at the time, because Safeway had refused to stop purchasing grapes from farms the UFW was also striking against for unfair pay and harsh conditions. During both of these strikes the Black Panther Party published support for the strikes in their weekly party newspaper, distributed nationally and internationally. In addition to supporting the strike the paper also emphasized that Safeway had never donated to the Free Breakfast Program.

The Black Panther Party's boycott of Safeway stores was a tremendous contribution to the UFW's boycott efforts. When the Panthers set up pickets at Safeway stores, they were an intimidating sight with their black leather jackets, berets, and dark glasses. UFW organizer Gilbert Padilla recalled that when he organized the grape boycott in the Los Angeles area, Panthers on the picket line acted as a restraint on police harassment because the Panthers "scared the hell out of them." More importantly, the party's boycott of Safeway was well organized and innovative. Bobby Seale, like many other Panthers, had served in the military, and drawing on his experience in the U.S. Air Force, Seale created a "motor pool" for party use that was employed in the Safeway boycott. In the evenings when people went shopping for groceries, party members would not only explain to them why they should be boycotting Safeway, but they also provided transportation to the Lucky's grocery stores, which had donated to the Free Breakfast for Children Program and had agreed not to sell California grapes.[14]

The Black Panther Party's support of the UFW strike and their motor pool forced the Safeway store located at 27th and West streets in Oakland to close. Declaring solidarity with the UFW and materially supporting the strike clearly established connections between varying races in relation to Food Sovereignty, fair treatment of workers, fair pay, police brutality, and capitalism. Beyond these connections this solidarity illustrated the power communities have in supporting one another independent of capitalism.

Through the pursuit of Food Sovereignty and the party's ten point platform a clear connection can be made to environmental justice through the right to healthy food and clean drinking water. Minority communities are far more likely[15] to be exposed to environmental harms across the so called united states and across the world; Environmental harms caused by capitalism and its inherent environment destroying extraction and pollution. Food Sovereignty and environmental justice both require the right to self-determination free from capitalist exploitation and environmental destruction.[16]

Party Branches

Oakland and San Francisco

The free breakfast programs in Oakland and later San Francisco garnered support from people from various walks of life and resulted in many donations to the program and general support from moderate white people. FBI Director Hoover, in a memo to a San Francisco surveillance officer in 1969, stated

One of our primary aims in counterintelligence as it concerns the [Black Panther Party] is to keep this group isolated from the moderate black and white community which may support it ... ... This is most emphatically pointed out in their Breakfast for Children Program, where they are actively soliciting and receiving support from uninformed whites and moderate blacks.[17]

Chicago

Fred Hampton, chairman of the Chicago Branch of the Black Panther Party gave a speech on April, 29th, 1969 explaining the connections between capitalism and young Black children not having food to eat. He explained the steps the Free Breakfast Program were taking to eradicate the hunger prevalent throughout their communities and across the country.[18] Hampton stated:

Our Breakfast for Children program is feeding a lot of children and the people understand our Breakfast for Children program. We sayin’ something like this—we saying that theory’s cool, but theory with no practice ain’t shit. You got to have both of them—the two go together. We have a theory about feeding kids free. What’d we do? We put it into practice. That’s how people learn. A lot of people don’t know how serious the thing is. They think the children we feed ain’t really hungry. I don’t know five year old kids that can act well, but I know that if they not hungry we sure got some actors. We got five year old actors that could take the academy award. Last week they had a whole week dedicated to the hungry in Chicago. Talking ’bout the starvation rate here that went up 15%. Over here where everybody should be eating. Why? Because of capitalism. [19]

About a month after this speech a memo Signed by FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, conveyed how the FBI viewed the free breakfast program as a threat to national security:

You state that the bureau should not attack programs of community interest such as the BPP “Breakfast for Children Program.” . . . You have obviously missed the point. The BPP is not engaged in the program for humanitarian reasons. This program was formed by the BPP . . . to create an image of civility, assume community control of Negroes, and fill adolescent children with their insidious poison.[20]

A former Black Panther Party member spoke on the Chicago police department attempting to disrupt the food program,

It was a lot of organizing because of course we had to go out and find people to give us food for the program and all that. . . . Anyways, the night before it [the first breakfast program in Chicago] was supposed to open, the Chicago police broke into the church where we had the food and mashed up all the food and urinated on it. So we had to delay the opening. But what that caused was just all kinds of attention, and people were just lining up to give us donations.[21]

On December 4th 1969 the Chicago police department in coordination with the FBI kicked down the doors of the apartment where Fred Hampton and his pregnant girlfriend were sleeping. They shot and killed Mark Clark, who was on guard at the time. As Mark Clark was dying he fired one shot at the police, and this was the only shot fired from the Black Panther Party, while police fired fully automatic weapons at the apartment. One of the bullets hit Fred Hampton in the shoulder, and he was then killed, while asleep, after officers entered his bedroom and shot him point blank in the head, assassinating him; Hampton's girlfriend survived. Hampton was asleep during the assassination, because an FBI informant drugged him with secobarbital.[22]

The attention the murder of Hampton and Clark brought, especially because of Hampton’s visibility around the Breakfast Program, helped to marshal increased grassroots support among African American radicals but also liberal whites. The program became a vehicle, therefore, not only for providing sustenance to children but also as a cause around which to organize the space of the black community in particularly scaled ways.[23]

Los Angeles

In Los Angeles Flores Forbes spoke to community members about how the breakfast program would help children “grow and intellectually develop because children can’t learn on empty stomachs.” The breakfast program fed around 1,200 children a week in Los Angeles. [24]

On December, 8th, 1969 the first SWAT raid to be conducted in the so called United States was undertaken at the Los Angeles Branch Head Quarters of the Black Panther Party. More than 350 police officers were involved in the raid to allegedly execute arrest warrants; There were 13 Black Panther members in the building including three women and five teenagers. The LAPD would detonate explosives on the roof of the headquarters and call in a tank for reinforcements during the raid. Bernard Arafat, a Black Panther Party member,

awoke to explosions rocking the library of the Black Panthers’ 41st and Central Avenue headquarters in Los Angeles. Above him, footsteps stomped across the roof. Then gunfire erupted. Arafat wasn’t a seasoned Panther. He was a 17-year-old runaway from juvenile hall whose parents had both died when he was 13. After years of committing small-time crimes, Arafat was taken in by the Panthers and gained a sense of purpose. He helped with the organization’s breakfast program, feeding hungry kids on their way to school.[25]

According to the Los Angeles Police Department the Special Weapons Assault Team (SWAT,) was originally created so the police force could respond to sniper and hostage situations, like situations that allegedly occurred during the Watts Rebellion, but the occurrence of these events were rare (less than 5% of SWAT raids are for the original mission of the unit across the country today,[26]) so the SWAT unit had never been deployed prior to the raid on the Black Panther Party's headquarters.

In its Panther deployment, SWAT was transformed from a tool of surgical precision into a blunt-force battering ram, and that’s ultimately how it would find its calling in police departments across the country — especially in African American communities.[27]

The raid resulted in

13 arrests and a total of 72 criminal counts being filed. But at trial, the Panthers’ attorneys, including a young Johnnie Cochran, argued that the group had acted in self-defense. SWAT had entered the building unannounced with guns blazing. A mixed-race jury agreed, finding the Panther defendants not guilty on almost all charges, including the most serious ones of assault with a deadly weapon and conspiracy to murder policemen. Arafat, who had skipped bail and fled underground to Puerto Rico, returned to Los Angeles.[28]

Houston

... On July 26 of [1970], Carl Hampton spoke to a crowd of about one hundred people. Although only twenty-one years old, Hampton had emerged as an important political force in the city's Black community. After a sojourn in Oakland, California, where he witnessed the Black Panther Party's efforts to "serve the people" through free breakfast programs for children and through patrols that monitored and challenged police misconduct, Hampton started the People's Party 2 in Houston. He directed the group's efforts to feed and clothe poor people in the Third Ward from the party's headquarters in the 2800 block of Dowling... The material deprivation of Black people loomed large in shaping Hampton's politics. "If black people did not live in substandard housing, poor conditions, or suffer all the other unequal indignities," he declared, "there would be no People's Party 2.[29]

New York

COINTELPRO

The Black Panther Party was victim to the FBI's violent, covert and illegal operation known as COINTELPRO, or Counter Intelligence Program. According to a memo from FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover the goal of COINTELPRO was

... to expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit, or otherwise neutralize the activities of black nationalist, hate-type organizations and groupings, their leadership, spokesmen, membership, and supporters, and to counter their propensity for violence and civil disorder.[30]

Hoover called the free breakfast program “potentially the greatest threat to efforts by authorities to neutralize the BPP and destroy what it stands for,” and authorized extremely grotesque police counter-measures to destroy it. These operations ranged from disinformation campaigns telling parents in San Francisco that the food was infected with venereal disease, to the Chicago police breaking into a Church the night before its first food services to mash up and urinate on the children's breakfasts.[31]

Legacy of Free Breakfast Program

Peoples Kitchen Collective

The legacy of the Black Panther Party and their survival programs, including the free breakfast program, lives on in Oakland and beyond. One organization that was inspired by the Black Panther Party's Free Breakfast program is the Peoples Kitchen Collective in West Oakland and according to their website they cook:

a Free Breakfast each year at the Life is Living festival in West Oakland. Since 2011, we have served over 7,000 breakfasts made from donations by local food businesses and urban farms. The menu has included creamy grits, collard greens, tofu or egg scramble, and sweet potato biscuits. It is a meal made with love, by community for community, so that all of us can survive together in the face of rampant white supremacy and gentrification. This a meal to feed hope and fuel the resistance. We have looked to these resources -- foundations, archives, libraries, and bookstores, to learn about the powerful history on whose shoulders we stand. These projects and organizations are continuing the legacy of the Panthers in the Bay Area and beyond.[32]

A former Black Panther, Billy X Jennings, who serves as an archivist was a part of the original Free Breakfast Program. [33]

Planting Justice

According to their website: "Since 2009 Planting Justice has built over 550 edible permaculture gardens in the San Francisco Bay Area, worked with five high-schools to develop food justice curricula and created over 40 green jobs in the food justice movement for people transitioning from prison." Their tenets include: Food Sovereignty, Economic Justice, and Community Healing.[34]

The impact the Black Panther Party had on the Planting Justice program is evident: "The Black Panther Party’s 10 point program is a valuable tool for teaching liberation education. It not only gives students a deeper understanding of the civil rights movement, it further provides a container for participants to connect this history to their individual experience and discuss the most pressing issues in their community. Participants learn about the alliances built between the Black Panther Party and the United Farm Workers during their grape boycott and everyone gets to enjoy a fruit salad made with produce grown on local unionized organic farms."[35]

Furthermore, on a blog post on their website Haleh Zandi explains the importance of alliance building in the context of white supremacy and Food Sovereignty:

Alliance building is, in fact, a necessary means for achieving social change towards justice and human rights, and within the food justice movement in the United States, addressing white, middle-class privilege is one of the keys to building alliances between grassroots organizations working for sovereignty over affordable, nutritious food sources. Failure to confront social and cultural differences within liberal social movements and the ways in which the community food movement reproduces white privilege undermines the efforts of social change (Slocum 2006). As evidenced above, racism is an organizing process in the industrialized and globalized food system: people of color disproportionately experience food insecurity, lose their farms, and face the dangerous work of food processing and agricultural labor. Between 1990 and 1998, the total number of young Indigenous Americans who deal with diabetes increased by 71% (Acton et al 2002), and Indigenous Americans are 2.6 times more likely than European Americans to have diabetes, which has a direct correlation with one’s diet. Likewise, African American and Latino American households experienced food insecurity at double the national average in 2003 (Weil 2004; or see Shields 1995). Indeed, the United States’ food system was built upon a foundation of genocide, slavery, and racist institutions which have dispossessed racialized groups of cultural pride, land use, and the right to a dignified livelihood through the overlapping dynamics of race, class, and gender disparities.[36]

Food Justice Movement

A major legacy of the Free Breakfast Program is the food justice movement it helped catalyze. The Party played a leading role in approaching food through a revolutionary lens, inspiring numerous food-related initiatives “used as a tool to develop a set of community-based solutions that might help transform the very political and economic systems that had historically oppressed low-income and ethnic minority communities.”[37]

This reflected the view of David Hillard, former Chief of Staff of the Black Panther Party, that "we’ve always been involved in food, because food is a very basic necessity, and it’s the stuff that revolutions are made of."[38]

USDA School Breakfast Program

By 1969, the success of the program had become a matter of federal policy debate, with the National School Lunch Program administrator admitting in a 1969 U.S. senate hearing that the Panthers were feeding more poor school children than the State of California.[39]

According to History.com:

The public visibility of the Panthers’ breakfast programs put pressure on political leaders to feed children before school. The result of thousands of American children becoming accustomed to free breakfast, former party member Norma Amour Mtume told Eater, was the government expanded its own school food programs. Though the USDA had piloted free breakfast efforts since the mid 1960s, the program only took off in the early 1970s—right around the time the Black Panthers’ programs were dismantled. In 1975, the School Breakfast Program was permanently authorized.[40]

In response:

The BPP saw such actions as an unfair co-option on the part of establishment actors who looked to minimize the BPP’s importance and to move the control of community program development and management away from low-income Black communities themselves. Such co-option represented another factor that led to the slow demise of the BPP’s influence in communities across the nation.[41]

It was not until a new set of waivers were established in 2020 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic that a complicated and often stigmatizing bureaucratic application process was eliminated, and free lunches were provided for all students. Before this new expansion, as many as 75% of U.S. school districts had unpaid "student meal debt."[42] After the federal breakfast programs were established, noticeable improvements in students' levels of focus, energy, and reduced stress were observed by teachers, while schools no longer had to deal with unnecessary paperwork.[43]

This expansion proved short-lived. In 2022, federal school meal programs faced a "perfect storm" according to Diane Pratt-Heavner, spokesperson for the School Nutrition Association.[44]. Even though a poll in 2021 found that "74% of Americans support making universal free school meals permanent nationwide," the Democratic Party's surrender to Republican opposition led to the expiration of this highly popular policy, once again excluding tens of millions of students from receiving free meals.[45][46]

Sources

- ↑ https://www.aaihs.org/the-black-panther-party/

- ↑ https://www.history.com/news/free-school-breakfast-black-panther-party

- ↑ Nik Heynen (2009) Bending the Bars of Empire from Every Ghetto for Survival: The Black Panther Party's Radical Antihunger Politics of Social Reproduction and Scale, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 99:2, 406-422, DOI: 10.1080/00045600802683767

- ↑ https://www.eater.com/2016/2/16/11002842/free-breakfast-schools-black-panthers

- ↑ https://www.pbs.org/hueypnewton/actions/actions_survival.html

- ↑ https://www.historyisaweapon.com/defcon1/fhamptonspeech.html

- ↑ https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/primary-documents-african-american-history/black-panther-party-ten-point-program-1966/

- ↑ https://libcom.org/article/huey-newton-introduces-revolutionary-intercommunalism-boston-college-november-18-1970

- ↑ https://emorywheel.com/the-black-panthers-and-young-lords-how-todays-mutual-aid-strategies-took-shape/

- ↑ https://www.gejp.es.ucsb.edu/sites/secure.lsit.ucsb.edu.envs.d7_gejp-2/files/sitefiles/publication/PEJP%20Annual%20Report%202018.pdf#page=11

- ↑ https://truthout.org/articles/capitalist-economies-overproduce-food-but-people-cant-afford-to-buy-it/

- ↑ https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/apr/28/indigenous-americans-drinking-water-navajo-nation and shelter,

- ↑ Araiza, Lauren. “‘In Common Struggle against a Common Oppression’: The United Farm Workers and the Black Panther Party, 1968-1973.” The Journal of African American History, vol. 94, no. 2, 2009, pp. 200–23. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25610076. Accessed 10 Jan. 2023.

- ↑ Araiza, Lauren. “‘In Common Struggle against a Common Oppression’: The United Farm Workers and the Black Panther Party, 1968-1973.” The Journal of African American History, vol. 94, no. 2, 2009, pp. 200–23. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25610076. Accessed 10 Jan. 2023.

- ↑ https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/news/press-releases/racial-ethnic-minorities-low-income-groups-u-s-air-pollution/

- ↑ https://therednation.org/revolutionary-socialism-is-the-primary-political-ideology-of-the-red-nation-2/

- ↑ https://www.eater.com/2016/2/16/11002842/free-breakfast-schools-black-panthers

- ↑ Nik Heynen (2009) Bending the Bars of Empire from Every Ghetto for Survival: The Black Panther Party's Radical Antihunger Politics of Social Reproduction and Scale, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 99:2, 406-422, DOI: 10.1080/00045600802683767

- ↑ https://www.marxists.org/archive/hampton/1969/04/27.htm

- ↑ Nik Heynen (2009) Bending the Bars of Empire from Every Ghetto for Survival: The Black Panther Party's Radical Antihunger Politics of Social Reproduction and Scale, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 99:2, 406-422, DOI: 10.1080/00045600802683767

- ↑ Nik Heynen (2009) Bending the Bars of Empire from Every Ghetto for Survival: The Black Panther Party's Radical Antihunger Politics of Social Reproduction and Scale, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 99:2, 406-422, DOI: 10.1080/00045600802683767

- ↑ ↑ Nik Heynen (2009) Bending the Bars of Empire from Every Ghetto for Survival: The Black Panther Party's Radical Antihunger Politics of Social Reproduction and Scale, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 99:2, 406-422, DOI: 10.1080/00045600802683767

- ↑ Nik Heynen (2009) Bending the Bars of Empire from Every Ghetto for Survival: The Black Panther Party's Radical Antihunger Politics of Social Reproduction and Scale, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 99:2, 406-422, DOI: 10.1080/00045600802683767

- ↑ https://www.aaihs.org/the-black-panther-party/

- ↑ https://www.latimes.com/opinion/story/2019-12-08/50-years-swat-black-panthers-militarized-policinglos-angeles

- ↑ https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.1805161115

- ↑ https://www.latimes.com/opinion/story/2019-12-08/50-years-swat-black-panthers-militarized-policinglos-angeles

- ↑ https://www.latimes.com/opinion/story/2019-12-08/50-years-swat-black-panthers-militarized-policinglos-angeles

- ↑ Ruth Thompson-Miller, How Racism Takes Place By George Lipsitz Temple University Press. 2008. 310 pages. $27.95, Social Forces, Volume 93, Issue 4, June 2015, Page 149, https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sot021

- ↑ https://rethinkingschools.org/articles/cointelpro-teaching-the-fbi-s-war-on-the-black-freedom-movement/

- ↑ https://www.history.com/news/free-school-breakfast-black-panther-party

- ↑ http://peopleskitchencollective.com/panthers-legacy

- ↑ https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/oct/17/black-panther-party-oakland-free-breakfast-50th-anniversary

- ↑ https://plantingjustice.org/about/

- ↑ https://plantingjustice.org/black-panther-party-10-point-program/

- ↑ https://plantingjustice.org/planting-justice/resources-food-justice-research-racial-equality/

- ↑ https://timeline.com/the-black-panthers-helped-free-breakfast-programs-9e4756d93510

- ↑ Garrett Broad, "More than Just Food: Food Justice and Community Change"

- ↑ https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/black-panther-partys-free-breakfast-program-1969-1980/

- ↑ https://www.history.com/news/free-school-breakfast-black-panther-party

- ↑ Garrett Broad, "More than Just Food: Food Justice and Community Change"

- ↑ https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/jun/04/us-school-hunger-crisis-federal-waivers-end

- ↑ https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/free-school-lunches-are-ending-house-passes-deal-summer-meals-child-nu-rcna34745

- ↑ https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/free-school-lunches-set-end-creating-perfect-storm-high-inflation-rcna33688

- ↑ https://melmagazine.com/en-us/story/black-panthers-free-breakfast-program

- ↑ https://www.npr.org/2022/10/26/1129939058/end-of-nationwide-federal-free-lunch-program-has-some-states-scrambling