Capitalism

Malcolm X on Capitalism: "It is impossible for capitalism to survive, primarily because the system of capitalism needs some blood to suck. Capitalism used to be like an eagle, but now it’s more like a vulture. It used to be strong enough to go and suck anybody’s blood whether they were strong or not. But now it has become more cowardly, like the vulture, and it can only suck the blood of the helpless. As the nations of the world free themselves, then capitalism has less victims, less to suck, and it becomes weaker and weaker. It’s only a matter of time in my opinion before it will collapse completely."[1]

Capital does not just rob the soil and worker, as Marx observes, it necrotizes the entire planet. Here is a “metabolic rift”— between earth and labor—driven by the contradictions of endless accumulation. That accumulation is not only productive; it is necrotic, unfolding a slow violence, occupying and producing overlapping historical, biological, and geological temporalities. Capital is the Sixth Extinction personified: it feasts on the dead, and in doing so, devours all life. The deep time of past cataclysm becomes the deep time of future catastrophe; the residue of life in hydrocarbons becomes the residue of capital in petrochemical plastics. Capitalism leaves in its wake the disappearance of species, languages, cultures, and peoples. It seeks the planned obsolescence of all life. Extinction lies at the heart of capitalist accumulation.[2]

Summary

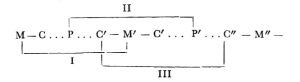

"There are three circuits in the total circulation process of capital: I) the circuit of money capital, M . . . M', II) the circuit of productive capital, P . . . P', and III) the circuit of commodity capital, C' . . . C". The capitalist begins with a certain amount of money capital M; he buys commodities in the form of means of production and labour power, which he engages in a production process P, from which emerges another set of commodities C' which in turn becomes commodity capital when the capitalist takes it to the market to be exchanged for a larger sum of money M'. This is how individual capital accomplishes its self-expansion. It can be presented schematically as follows:"[3]

"The three circuits of capital are overlapping, such that any particular unit of capital simultaneously belongs to all the circuits at any given moment. The conditions of movement of the three types of capital, however, are not uniform. The history of evolution of imperialism illustrates the point. In the classical era of imperialism, of which Adam Smith, Ricardo and Marx wrote, it was commodity capital that crossed the national boundary of advanced capitalist country in the form of exported goods. The next phase of imperialism, which was identified by Lenin, saw the internationalization of money capital, that is, the "export of capital." In the latest phase of imperialism, the productive capital is internationalized as transnational corporations spread their wings."[4]

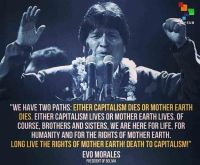

Climate Collapse

See Also: Anthropocene | Sixth Mass Extinction | Industrial Agriculture

Many authors, publications, scientists etc. have made the connection between capitalism/ unfettered economic growth and Climate Collapse. [5][6] Capitalism is predicated around endless growth and consumption[7] and these processes are causing a disruption in the Earth's natural Equilibrium[8] through the extraction of resources[9], land-use change[10] and burning of fossil fuels.[11]

"Why Capitalism is Killing Us (And The Planet)": https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-qxP2TzYcNw

"Arundhati Roy: Capitalism Is “A Form of Religion” Stopping Solutions to Climate Change & Inequality": https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UyCkFoSIwWg

"Capitalism Is Destroying Us - The New Climate Report": https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pvRtNGW9Ajk

"How Capitalism Exploits Natural Disasters": https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qSl6OSx3Y-8

Terracide

https://climateandcapitalism.com/2013/05/23/terracide-destroying-the-planet-for-profit/

Industrial Agriculture

However, the celebrated efficiency of industrial capitalist agriculture must also be seen to depend on an array of un- and undervalued costs. Some of these costs can be easily ignored and externalized, without posing a threat to the operative logic of the system. These include: the contribution to chronic epidemiological problems (e.g. obesity, cardiovascular disease) and the extensive burden on health-care systems; the costs of managing and responding to disease threats such as swine and avian flu, listeriosis, E. coli and mad cow; the diffuse impacts of fertilizer, chemical and other waste runoff from industrial monocultures and factory farms on terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems and human health; the associated costs of water treatment; an assortment of workplace health concerns (e.g. high rates of repetitive stress and accidental injuries); the psychological violence associated with factory farms and industrial slaughterhouses; chemical-laden environments; and the immeasurable suffering of rising populations of animals reared in intensive confinement, along with the unquantifiable ethical issues that this entails.

Other externalized costs, however, are deeply contradictory in that they mask the deterioration of the very biophysical foundations of agriculture. These include the undervaluation of the damage associated with: soil erosion and salinization; the overdraft of water and threats to its long-term supply; the loss of biodiversity and crucial ‘ecosystem services’ (e.g. pollination, soil formation); and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. In addition, there is a failure to account for the intractable dependence of industrial methods upon a finite resource base, particularly fossilized biomass. All of these biophysical contradictions – or sources of long-term instability – are magnified by the increasing intensity and volume of livestock production. Because so much usable nutrition is lost in cycling feed through animals, agriculture’s ‘footprint’ in the landscape necessarily expands as per capita meat production rises beyond the densities of small integrated farms and non-cultivatable pasture, as does the use of energy and agro-inputs. An expanding ‘ecological hoofprint’ is thus implicated in the loss of forests, grasslands and wet-lands, which has a major impact on the carbon cycle, both in the release of carbon as diverse ecosystems are converted to agriculture, and in the diminished capacity for carbon sequestration.The world’s livestock population is also a leading source of two other GHGs, methane and nitrous oxide, which are much smaller by volume than carbon dioxide but more potent per unit. 3 When this atmospheric burden is aggregated, the growth in global livestock population emerges as one of the largest contributors to climate change, which again fails to register in the conventional conception of productivity.[12]

Mono-cultures

Biodiversity Loss

Continual growth drives industrial expansion and accelerates communications and trade dynamics, resulting in overconsumption of materials and energy, conversion of large portions of land for human use, and an unsustainable increase in waste and emissions. Consumption and production patterns that fuel growth are responsible for the environmental degradation in the Anthropocene and have led to large increases in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and climate change, a profound transformation of the planet, and huge negative impacts on biodiversity. Biodiversity loss and climate change are closely interconnected; they share common drivers (human activities) and have predominantly negative impacts on human well-being and quality of life.[13]

Although science and governmental policies have long strived for biological diversity protection, biodiversity has continuously declined. Ecosystems are deteriorating at unprecedented rates and approximately 1 million species are in danger of extinction. The last UN report, Global Biodiversity Outlook 5, concludes that, as in the case of the 2010 biodiversity targets, the 2020 Aichi Targets have not been met. The spiraling biodiversity loss will have multiple and multidimensional cascading effects that will lead to drastic changes in ecosystems dynamics and functioning. The growth-driven biodiversity collapse over the past century is causing the loss of ecological interactions, functions, redundancy, codependencies, structural complexity, and mechanisms of resilience that characterize natural systems. The COVID-19 crisis not only demonstrates the fragility of a socioeconomic system unaligned with nature, but also has resulted in the shutdown of conservation programs reliant on ecotourism for funding, which will affect biodiversity protection. This is strong evidence of the dependence of conservation funding on economic growth.[14]

Characteristics

Surplus Value

"Value created by the unpaid labor of wage workers, over and above the value of their labor power, and appropriated without compensation by the capitalist. Surplus value is a specific expression of the capitalist form of exploitation, in which the surplus product takes the form of surplus value. The production and appropriation of surplus value constitute the essence of the fundamental economic law of capitalism. K. Marx pointed out that “production of surplus value is the absolute law” of the capitalist mode of production. This law reflects not only the economic relations between capitalists and wage workers but also the economic relations between various groups of the bourgeoisie— industrialists, merchants, and bankers— and between them and the landowners. The pursuit of surplus value plays the chief role in the development of the productive forces under capitalism and determines and channels the development of production relations in capitalist society. The doctrine of surplus value, which Lenin called “the cornerstone of Marx’ economic theory”, was first elaborated by Marx in 1857-58 in the manuscript of “A Critique of Political Economy” (the first draft of Das Kapital). However, a few of the propositions in the theory of surplus value are encountered in works written by Marx during the 1840’s— Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, The Poverty of Philosophy, and Wage Labor and Capital."[15]

Continual Growth

Karl Marx wrote: "Except as personified capital, the capitalist has no historical value, and no right to that historical existence, which, to use an expression of the witty Lichnowsky, “hasn’t got no date.” And so far only is the necessity for his own transitory existence implied in the transitory necessity for the capitalist mode of production. But, so far as he is personified capital, it is not values in use and the enjoyment of them, but exchange-value and its augmentation, that spur him into action. Fanatically bent on making value expand itself, he ruthlessly forces the human race to produce for production’s sake; he thus forces the development of the productive powers of society, and creates those material conditions, which alone can form the real basis of a higher form of society, a society in which the full and free development of every individual forms the ruling principle. Only as personified capital is the capitalist respectable. As such, he shares with the miser the passion for wealth as wealth. But that which in the miser is a mere idiosyncrasy, is, in the capitalist, the effect of the social mechanism, of which he is but one of the wheels. Moreover, the development of capitalist production makes it constantly necessary to keep increasing the amount of the capital laid out in a given industrial undertaking, and competition makes the immanent laws of capitalist production to be felt by each individual capitalist, as external coercive laws. It compels him to keep constantly extending his capital, in order to preserve it, but extend it he cannot, except by means of progressive accumulation."[16]

Alienation

"How Capitalism Causes Loneliness" (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BwQCnltp9lo)

"We have seen that the growing accumulation of capital implies its growing concentration. Thus grows the power of capital, the alienation of the conditions of social production personified in the capitalist from the real producers. Capital comes more and more to the fore as a social power, whose agent is the capitalist. This social power no longer stands in any possible relation to that which the labour of a single individual can create. It becomes an alienated, independent, social power, which stands opposed to society as an object, and as an object that is the capitalist's source of power."[17]

Exploitation

In reality, Marx thought, workers’ labor under capitalism is neither truly voluntary nor entirely for the benefit of the workers themselves. It is not truly voluntary because workers are forced by their lack of ownership of the means of production to sell their labor power to capitalists or else starve. And workers are not laboring entirely for their own benefit because capitalists use their privileged position to exploit workers, appropriating for themselves some of the value created by workers’ labor.

To understand Marx’s charge of exploitation, it is first necessary to understand Marx’s analysis of market prices, which he largely inherited from earlier classical economists such as Adam Smith and David Ricardo. Under capitalism, Marx argued, workers’ labor power is treated as a commodity. And because Marx subscribed to a labor theory of value, this means that just like any other commodity such as butter or corn, the price (or wage) of labor power is determined by its cost of production—specifically, by the quantity of socially necessary labor required to produce it. The cost of producing labor power is the value or labor-cost required for the conservation and reproduction of a worker’s labor power. In other words, Marx thought that workers under capitalism will therefore be paid just enough to cover the bare necessities of living. They will be paid subsistence wages.

But while labor power is just like any other commodity in terms of how its price is determined, it is unique in one very importance respect. Labor, and labor alone, according to Marx, has the capacity to produce value beyond that which is necessary for its own reproduction. In other words, the value that goes into the commodities that sustain a worker for a twelve-hour work day is less than the value of the commodities that worker can produce during those twelve hours. This difference between the value a worker produces in a given period of time and the value of the consumption goods necessary to sustain the worker for that period is what Marx called surplus value.

According to Marx, then, it is as though the worker’s day is split into two parts. During the first part, the laborer works for himself, producing commodities the value of which is equal to the value of the wages he receives. During the second part, the laborer works for the capitalist, producing surplus value for the capitalist for which he receives no equivalent wages. During this second part of the day, the laborer’s work is, in effect, unpaid, in precisely the same way (though not as visibly) as a feudal serf’s corvée is unpaid (Marx 1867).

Capitalist exploitation thus consists in the forced appropriation by capitalists of the surplus value produced by workers. Workers under capitalism are compelled by their lack of ownership of the means of production to sell their labor power to capitalists for less than the full value of the goods they produce. Capitalists, in turn, need not produce anything themselves but are able to live instead off the productive energies of workers. And the surplus value that capitalists are thereby able to appropriate from workers becomes the source of capitalist profit, thereby “strengthening that very power whose slave it is” (Marx 1847: 40)[18]

Centralization of Wealth

Competition

"Competition is the completest expression of the battle of all against all which rules in modern civil society. This battle, a battle for life, for existence, for everything, in case of need a battle of life and death, is fought not between the different classes of society only, but also between the individual members of these classes. Each is in the way of the other, and each seeks to crowd out all who are in his way, and to put himself in their place. The workers are in constant competition among themselves as are the members of the bourgeoisie among themselves. The power-loom weaver is in competition with the hand-loom weaver, the unemployed or ill-paid hand-loom weaver with him who has work or is better paid, each trying to supplant the other. But this competition of the workers among themselves is the worst side of the present state of things in its effect upon the worker, the sharpest weapon against the proletariat in the hands of the bourgeoisie. Hence the effort of the workers to nullify this competition by associations, hence the hatred of the bourgeoisie towards these associations, and its triumph in every defeat which befalls them."[19]

Usury

"Usury abridges the general formula for capital (M-C-M' or buying a commodity-C with money-M in order to sell it for more money-M). The usurer reduces this formula into its purest form: M-M': 'money which is worth more money, value which is greater than itself' (Marx, Capital 257)."[20]

Karl Marx referred to Usury as "the original starting-point of capital," "the perversion and objectification of production relations in their highest degree," and "mystification of capital in its most flagrant form."[21]

Social Capital

Surveillance

Flows of information are therefore tightly connected to nature. Here we might reflect upon the connections between the planetary surveillance and imperial surveillance. We are witnessing the globalized data theft by the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA) and other intelligence “services,” in order to appropriate information necessary for control of the other earth systems. The twenty-first century is also the era of the robot world war. Killer drones, from Afghanistan to Somalia, Iraq, Syria, Yemen, and Palestine, are deployed to kill “terrorists”—defined as those who threaten the normal working of world systems which (we are told) are indispensable for “free peoples” in a “free world.” The struggles over energy and the climate have repercussions for all other earth systems and for human rights in general. The dominant narrative on capitalism’s globalization, a quarter century after the end of “actually existing socialism,” seems almost kitschy against the background of these planetary developments. Its repercussions are felt across all spheres of life: in politics and cultures, in the economy and in daily life.[22]

The State

Climate change brings extreme weather, drought, wild fires, flooding, in short, emergencies. Under conditions of modern capitalism, these emergencies, in turn, call forth the state. When the routine functioning of production and consumptive reproduction is paralyzed by some weather event, we see the real relationship between capital and the state. In these moments, capital’s profound, even existential, dependence upon the core features of government comes into focus: legal authority, backed by legitimized organized violence; production for use, as in the public sector; and the need for mass, unified collective action and planning. Capital’s world of self-interest and private accumulation depends upon non-capitalist values, non-capitalist institutions, and non-capitalist forms of production and reproduction to survive. All this becomes glaringly apparent in a moment of crisis.

In responding to the climate crisis, it appears that the state will have to take on a broadly defined environmental mission. At first glance this might seem like a new task. In fact, the capitalist state has always been an inherently environmental entity. Elements of this argument can be found elsewhere. Just as capital does not have a relationship to nature but rather is a relationship to nature, so too is that relationship always also a relationship with the state, and mediated through the state. To put it even more directly: the state does not have a relationship with nature, it is a relationship with nature because the web of life and its metabolism—including the economy—exist upon the surface of the earth, and because the state is fundamentally a territorial institution.

Thus, I am bringing the state into Moore’s conception of capitalism as a world-ecology of capital, power, and nature (2015a). My core argument is this: the state is an inherently environmental entity, and as such, it is at the heart of the value form. The state is at the heart of the value form because the use values of nonhuman nature are, in turn, central sources of value. The modern state delivers these use values to capital. The state is therefore central to our understanding of the valorization process and to our discussion of the Capitalocene.

This argument becomes clear by explicitly connecting a few common ideas that are already implicitly linked. First, accept that the capitalist state by definition must work to reproduce the conditions of accumulation. Second, acknowledge the importance of nonhuman nature’s “use values” in the production of exchange values. Third, consider the location of these preexisting natural use values. Where do we find “nature” and its utilities? In the biosphere, which is to say: upon the surface of the earth. Fourth, now consider again the state’s obvious but undertheorized “territoriality.” The modern state is fundamentally geographic; it is territory. Now tie all these together: the preexisting use values of nonhuman nature are essential to capitalist accumulation, and these are found upon the surface of the earth. What institutions ultimately control the surface of the earth? States.[23]

Origins of Capitalism

https://sci-hub.ru/https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03066150008438748

https://www.cooperative-individualism.org/wood-ellen_agrarian-origins-of-capitalism-1998-jul-aug.pdf

Slavery and Capitalism

Exploiting the demographic catastrophe, capitalism created a novel “tropical” ecology in the slave plantation. Tropical zones—as much created as discovered—became a homogenized equatorial region whose native diversity was destroyed and replaced by a few staple crops such as sugar, tobacco, and coffee. This climatic-geographic differentiation allowed for the ecological othering of colonial subjects, justifying capitalist expansion by creating zones of law and exclusion. This geographical othering was a self-fulfilling prophecy: the more the plantation system grew, the more the ecological transformations it wrought allowed for malaria and yellow fever to thrive to new epidemic proportions, the more Europeans viewed these places as unsuitable for “civilization,” and inhospitable to settlement by “civilized” peoples. The myth that the demand for West African slaves was due to their immunity to the Caribbean disease environment is backward. First, indigenous populations collapsed, propelled by the imperial reorganization of natures. Then, African slaves were imported well before the flourishing of malaria and yellow fever, which had not existed in the New World prior to the European invasion.[24]

https://sci-hub.ru/https://muse.jhu.edu/article/580865/summary

https://www.jstor.org/stable/650442?casa_token=cpO5UM1ZcTkAAAAA%3AUxnyT-gW4_IbZoMbeDjBFh0k6qSjvYBeRd2kbvjaoHRqZAQNOR2NN8tSH3lX2kFbFtiX7NzIxg1lVP_JRFMdZc1ZS4f371TVlzkTs06rqGSUmyFu5EvN

Sugar

Sugar cane was first carried to the New World by Columbus on his second voyage, in 1493; he brought it there from the Spanish Canary Islands. Cane was first grown in the New World in Spanish Santo Domingo; it was from that point that sugar was first shipped back to Europe, beginning around 1516. Santo Domingo's pristine sugar industry was worked by enslaved Africans, the first slaves having been imported there soon after the sugar cane. Hence it was Spain that pioneered sugar cane, sugar making, African slave labor, and the plantation form in the Americas. Some scholars agree with Fernando Ortiz that these plantations were "the favored child of capitalism," and other historians quarrel with this assessment. But even if Spain's achievements in sugar production did not rival those of the Portuguese until centuries later, their pioneering nature has never been in doubt...[25]

...Few people sitting for breakfast in England in the 1700s knew that their tea was sweetened by sugar harvested under brutal conditions by African slaves toiling in the West Indies. The slaves remained far removed from the British breakfast table until a band of abolitionists placed the true picture of slavery directly in front of the English people. Stakeholders fought to maintain the system. They told the British public not to trust what they were told. They espoused the great humanity of the slave trade—Africans were not suffering, they were being “saved” from the savagery of the dark continent. They argued that Africans worked in pleasing conditions on the islands. When those arguments failed, the slavers claimed they made changes that remedied the offenses taking place on the plantations. After all, who was going to go all the way to the West Indies and prove otherwise, and even if they did, who would believe them?

The truth, however, was this—but for the demand for sugar and the immense profits accrued through the sale of it, the entire slavery-for-sugar economy would not have existed. Furthermore, the inevitable outcome of stripping humans of their dignity, security, wages, and freedom can only be a system that results in the complete dehumanization of the people exploited at the bottom of the chain.[26]

Coffee

https://is.muni.cz/el/fss/jaro2017/SAN106/_Sidney_W._Mintz__Sweetness_and_Power.pdf

Neoliberalism

Greenwashing

Regenerative Capitalism

In 2015, Former JP Morgan Chase Managing Director & President of the Capital Institute John Fullerton published the book "Regenerative Capitalism." At the ReGenFriends™ Summit in 2019, Fullerton was one of three speakers most prominently featured.[27] There, he proclaimed that "the Capital Institute has been at the forefront of regenerative economics," which he defines as "an economic system that works to 'regenerate' capital assets." To "place a true value on the environment," he argues that we need to recognize the Earth as "the original capital asset."[28]

In a 2020 joint report, "The Regenerative Revolution: A new paradigm for event management," Marriott International and IMEX Group cites the Capital Institute's "8 Principles for a Regenerative Economy" from "Regenerative Capitalism" as among the foundations of their work.[29]

Green Capitalism

On the spectrum of the defenders of green capitalism, there is a reformist variant that has gained a lot of attention recently: the Green New Deal, which calls for a program with hints of neo-Keynesianism in order to face the crisis. In the United States, this policy is supported by some candidates in the primaries of the Democratic Party, including Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, and also by the self-styled democratic socialist Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. The GND is also appearing in speeches and programs by European social-liberal parties like the PSOE or neoreformist tendencies like Podemos.

According to Ocasio-Cortez, the GND would allow the U.S. to transition to 100% renewable energy within 10 years, while creating millions of jobs linked to the construction of an efficient electrical grid throughout the country based on renewable technology, among other measures. How? By subsidizing billion-dollar corporations, the ones responsible for the current ecological crisis, so they can develop infrastructure to get us out of it. For this, they are to receive massive subsidies from the state.

The idea behind this perspective is that if the governments of the central industrialized countries in the world and the big multinational corporations become aware of the situation, they will be able to adopt measures to preserve the environment. Both the Green New Deal and similar proposals (like the UN Agenda 2020), which are reference points for many “progressive” forces around the planet, are based on the idea that “sustainable capitalism” is possible and that the corporations that created the crisis can become the saviors of the planet. But the illusion that the contradictions between capitalist interests and environmental preservation—affecting the lives of hundreds of millions of people—can be resolved is utopian and reactionary.

The capitalist mode of production is in total contradiction with nature and its processes of development. For capital, the determining factor in this process is merely quantitative. Fierce competition forces each capitalist to constantly seek ways to replace workers with machines that increase the productivity of labor and the mass of goods thrown onto the market. This increases the amount of natural resources needed to produce them. The constant repetition of production and reproduction of capital ruthlessly eats up all resources, without taking into account the time required for their natural production and regeneration.

The cause of this type of environmentally destructive development, rather than capitalist irrationality, is its inherent logic. It is the logical result of an economic system whose engine is the capitalists’ thirst for profit.[30]

Colonization

"I wasn’t against communism, but i can’t say i was for it either. At first, i viewed it suspiciously, as some kind of white man’s concoction, until i read works by African revolutionaries and studied the African liberation movements. Revolutionaries in Africa understood that the question of African liberation was not just a question of race, that even if they managed to get rid of the white colonialists, if they didn’t rid themselves of the capitalistic economic structure, the white colonialists would simply be replaced by Black neocolonialists. There was not a single liberation movement in Africa that was not fighting for socialism …

The whole thing boiled down to a simple equation: anything that has any kind of value is made, mined, grown, produced, and processed by working people. So why shouldn’t working people collectively own that wealth? Why shouldn’t working people own and control their own resources? Capitalism meant that rich businessmen owned the wealth, while socialism meant that the people who made the wealth owned it." - Assata Shakur[31]

Diffusionism

"Diffusionism is still, today, the foundation-theory for conservative beliefs about the rise of Europe and the "modernization" (read "civilization") of the Third World. Today it is accepted because colonialism, in various modern forms, remains a central and basic interest of the European elite, and it is still necessary to explain and rationalize a system by which European capital exploits non-European labor, mainly (but not only) for the purpose of persuading European populations that this exploitation is right, rational, and historically natural, and so persuade them to support the policies, pay the bills, and willingly endure the blood sacrifices. And today, still, an important component of this interest-bound theory is its tunnel-historical conception of the European past. It is still critically important to demonstrate that European social evolution has always been self-generated, owing nothing important to the non-European world, that Europe (or rather Western Europe, "the West") has always been, and remains today, ahead of the rest of the world in level and rate of development, that its economic character, and that progress for the non-European world can only come via the diffusion of European-based multinational capitalism."[32]

The Witch Trials

https://www.ppesydney.net/witch-hunts-and-the-birth-of-capitalism-reflections-on-caliban-and-the-witch/ -- Use Excerpts from Caliban and the Witch for this sub section

https://inthesetimes.com/article/capitalism-witches-women-witch-hunting-sylvia-federici-caliban

Alternatives

Human-Nature Arguments

Just Transition

Resistance to Capitalism

Urban Guerrillas

Security Culture

A rough translation of a chapter from Minimanual of the Urban Guerrilla written by Carlos Marighella -- a "Brazillian revolutionary who led the National Liberation Action (ALN). His tactics inspired the Italian Red Brigades, the German Red Army Faction, and the Provisional Irish Republican Army. Expelled from the Brazilian Communist Party for "pro-Cuban sympathy. Executed by police."[33] -- reads:

The urban guerrilla lives in constant danger of the possibility of being discovered or denounced. The primary security problem is to make certain that we are well-hidden and well-guarded, and that there are secure methods to keep the police from locating us. The worst enemy of the urban guerrilla, and the major danger that we run into, is infiltration into our organization by a spy or informer. The spy trapped within the organization will be punished with death. The same goes for those who desert and inform to the police. A well-laid security means there are no spies or agents infiltrated into our midst, and the enemy can receive no information about us even through indirect means. The fundamental way to insure this is to be strict and cautious in recruiting. Nor is it permissible for everyone to know everything and everyone. This rule is a fundamental ABC of urban guerrilla security. The enemy wants to annihilate us and fights relentlessly to find us and destroy us, so our greatest weapon lies in hiding from him and attacking by surprise.

The danger to the urban guerrilla is that he may reveal himself through carelessness or allow himself to be discovered through a lack of vigilance. It is impermissible for the urban guerrilla to give out his own or any other clandestine address to the police, or to talk too much. Notations in the margins of newspapers, lost documents, calling cards, letters or notes, all these are evidence that the police never underestimate. Address and telephone books must be destroyed, and one must not write or hold any documents. It is necessary to avoid keeping archives of legal or illegal names, biographical information, maps or plans. Contact numbers should not be written down, but simply committed to memory. The urban guerrilla who violates these rules must be warned by the first one who notes this infraction and, if he repeats it, we must avoid working with him in the future. The urban guerrilla's need to move about constantly with the police nearby—given the fact that the police net surrounds the city—forces him to adopt various security precautions depending upon the enemy's movements. For this reason, it is necessary to maintain a daily information service about what the enemy appears to be doing, where the police net is operating and what points are being watched. The daily reading of the police news in the newspapers is a fountain of information in these cases. The most important lesson for guerrilla security is never, under any circumstances, to permit the slightest laxity in the maintenance of security measures and precautions within the organization.

Guerrilla security must also be maintained in the case of an arrest. The arrested guerrilla must reveal nothing to the police that will jeopardize the organization. he must say nothing that will lead, as a consequence, to the arrest of other comrades, the discovery of addresses or hiding places, or the loss of weapons and ammunition.[34]

Indigenous Resistance

Land

Since their first appearances in what they called the "New World," waves of European settlers, and then Americans, have been devoted to wresting land and its resources from Native peoples to sustain settler life. Patrick Wolfe argues that "Land is life-- or, at least, land is necessary for life. Thus, contests for land can be --indeed, often are-- contests for life." Targeted for elimination because of their status as the original peoples who lived on and with the land, Native people were eliminated as "Indians," while enslaved Africans were targeted for elimination for their labor. As Deborah Bird Rose points out, all Native people had to do to be in the way of settler colonization was to stay home.

The shift in the way land is conceived of, even by Native peoples, is through capitalism, which regards land as property. Capitalism organized around the private ownership of the means of production (land, resources, capital) and the private control of the wealth produced by wage laborers became the means through which Native peoples were dispossessed of approximately 97 percent of land in the current United States. By the late nineteenth century and into the early twentieth century, Native people had been removed onto small tracts of land deemed wastelands by settlers. The 97 percent of remaining lands outside of these "reservations" were developed into bordertowns, which carried with them all the legal, social, and spatial fictions that made these lands alien and hostile to Indians who happened to wander "off the reservation."[35]

Sources

- ↑ https://blackagendareport.com/interview-malcolm-x-and-young-socialist-1965

- ↑ Moore, Jason W., "Anthropocene or Capitalocene? Nature, History, and the Crisis of Capitalism" (2016).Sociology Faculty Scholarship; Page: 116

- ↑ Sau, R. (1979). On the Laws of Concentration and Centralization of Capital. Social Scientist, 8(3), 3. doi:10.2307/3520387

- ↑ Sau, R. (1979). On the Laws of Concentration and Centralization of Capital. Social Scientist, 8(3), 3. doi:10.2307/3520387

- ↑ http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/8478770.stm

- ↑ https://neweconomics.org/uploads/files/f19c45312a905d73c3_rbm6iecku.pdf

- ↑ Strauss, William S., "The fallacy of endless growth: Exposing capitalism's insustainability" (2008). Doctoral Dissertations. 463. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/463

- ↑ https://www.zoology.ubc.ca/~bittick/conservation/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Clark-York2005_Article_CarbonMetabolismGlobalCapitali.pdf

- ↑ https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/mar/12/resource-extraction-carbon-emissions-biodiversity-loss

- ↑ https://nca2018.globalchange.gov/chapter/5/

- ↑ https://www.clientearth.org/latest/latest-updates/stories/fossil-fuels-and-climate-change-the-facts/

- ↑ WEIS, T. (2010). The Accelerating Biophysical Contradictions of Industrial Capitalist Agriculture. Journal of Agrarian Change, 10(3), 315–341. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0366.2010.00273.x

- ↑ https://conbio.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/cobi.13821

- ↑ https://conbio.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/cobi.13821

- ↑ https://www.marxists.org/archive/vygodsky/unknown/surplus_value.htm

- ↑ https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/ch24.htm

- ↑ https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1894-c3/ch15.htm

- ↑ https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/exploitation/#MarxTheoExpl

- ↑ https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1845/condition-working-class/ch05.htm

- ↑ https://cla.purdue.edu/academic/english/theory/marxism/terms/usury.html

- ↑ https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1894-c3/ch24.htm

- ↑ Moore, Jason W., "Anthropocene or Capitalocene? Nature, History, and the Crisis of Capitalism" (2016).Sociology Faculty Scholarship. Page, 139

- ↑ Moore, Jason W., "Anthropocene or Capitalocene? Nature, History, and the Crisis of Capitalism" (2016).Sociology Faculty Scholarship. Page, 166-167

- ↑ Moore, Jason W., "Anthropocene or Capitalocene? Nature, History, and the Crisis of Capitalism" (2016).Sociology Faculty Scholarship; Page: 121

- ↑ Mintz, S. W. (1986). Sweetness and power. Penguin Books. Page, 32-33

- ↑ Kara, S. (2023). Cobalt red: how the blood of the Congo powers our lives (First edition.). St. Martin's Press.

- ↑ https://www.regenfriends.com/events-1

- ↑ https://gritdaily.com/regenerative-economy/

- ↑ p. 46, 67, & 71; https://www.imexexhibitions.com/sites/default/files/2020-10/The_Regenerative_Revolution_.pdf

- ↑ https://www.leftvoice.org/capitalism-is-destroying-the-planet-lets-destroy-capitalism/

- ↑ https://www.liberationnews.org/assata-shakur-capitalism-socialism-anti-communism/

- ↑ Blaut, J. M. (1989). Colonialism and the Rise of Capitalism. Science & Society, 53(3), 260–296. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40404472

- ↑ https://www.marxists.org/subject/latinamerica/index.htm

- ↑ https://www.marxists.org/archive/marighella-carlos/1969/06/minimanual-urban-guerrilla/ch36.htm

- ↑ Estes, N., Benallie, B., Denetdale, J., Cody, R., Correia, D., & Yazzie, M. K. (2021). Red nation rising: From bordertown violence to native liberation; Page 120-121