Industrial Agriculture: Difference between revisions

Florez4747 (talk | contribs) |

Florez4747 (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

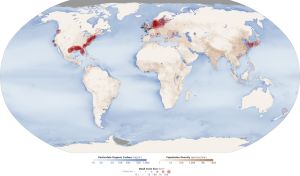

[[File:DeadZones.jpg||thumb|right|"The size and number of marine dead zones—areas where the deep water is so low in dissolved oxygen that sea creatures can’t survive—have grown explosively in the past half-century. Red circles on this map show the location and size of many of our planet’s dead zones. Black dots show where dead zones have been observed, but their size is unknown." Source: NASA<Ref>https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/44677/aquatic-dead-zones</Ref>]] | [[File:DeadZones.jpg||thumb|right|"The size and number of marine dead zones—areas where the deep water is so low in dissolved oxygen that sea creatures can’t survive—have grown explosively in the past half-century. Red circles on this map show the location and size of many of our planet’s dead zones. Black dots show where dead zones have been observed, but their size is unknown." Source: NASA<Ref>https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/44677/aquatic-dead-zones</Ref>]] | ||

Dead zones across the world will likely increase as the world is continually dependent on fertilizers for industrial agriculture crops<Ref>Rabalais, N. N., Díaz, R. J., Levin, L. A., Turner, R. E., Gilbert, D., and Zhang, J.: Dynamics and distribution of natural and human-caused hypoxia, Biogeosciences, 7, 585–619, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-7-585-2010, 2010.</Ref> | Dead zones across the world will likely increase as the world is continually dependent on fertilizers for industrial agriculture crops Global [[climate collapse]] has a high likely hood of worsening existing hypoxia zones and facilitating its formation in additional waters.<Ref>Rabalais, N. N., Díaz, R. J., Levin, L. A., Turner, R. E., Gilbert, D., and Zhang, J.: Dynamics and distribution of natural and human-caused hypoxia, Biogeosciences, 7, 585–619, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-7-585-2010, 2010.</Ref> | ||

Sources to begin with: <br> | Sources to begin with: <br> | ||

Revision as of 17:32, 23 June 2023

Industrial agriculture is a system of uniformity with no diversity: massive acres of land covered in identical nearly artificial plants; fed artificial nitrogen, potassium, and phosphorus; sprayed with toxic pesticides, insecticides and herbicides. In Who Really Feeds The World, Dr. Vandana Shiva explains how “an ecologically destructive and nutritionally inefficient food system has become the dominant paradigm in our minds and the most touted practice on our lands, even though, in reality, small, biodiverse farms working with nature’s processes produce most of the food we eat.”

Indigenous Persons across Turtle Island have long utilized place-based regenerative agriculture techniques. Placed-based regenerative agriculture is predicated around the reality of humans being but one part in the web of life, and understanding our role as stewards to the environment.

Fully comprehending our stewardship role on Earth is vital to reversing the destructive effects of industrialized society and agriculture. Anything short of fully embracing this role (which we all must fulfill) will have long lasting devastating effects for us, future generations, and all other life on Earth.[1]

CAFOS

CAFOS are 'Confined Animal Feeding Operations' and have increased, in the US, by 10% between 2012 and 2020. Hog production increased by 13 percent during the same time frame. There are ~8.7 billion animals in CAFO operations- animals include: Cattle, Dairy Cows, Hogs, Broiler Chickens, and Turkeys. The areas where animals are farmed is concentrated regionally across the country.[2]

The waste from hog and dairy operations is mainly held in open lagoons that contribute to NH3 and greenhouse gas (as CH4 and N2O) emissions. Emissions of NH3 from animal waste in 2019 were estimated at > 4,500,000 MT. Emissions of CH4 from manure management increased 66% from 1990 to 2017 (that from dairy increased 134%, cattle 9.6%, hogs 29% and poultry 3%), while those of N2O increased 34% over the same time period (dairy 15%, cattle 46%, hogs 58%, and poultry 14%).[3]

Artificial Fertilizers

Commercial artificial fertilizers are ubiquitously used across the so-called United States- with nitrogen (N) exceeding 12 million metric tonnes (MT) and is increasing annually at a rate of 60 thousand MT per year. Phosphorus (P) has remained constant for the last decade being used at a rate of 1.8 million MT per year.[4] Nitrogen applied by fertilizer is about 3 times greater than manure Nitrogen inputs and manure Phosphorus inputs are about equivalent to artificial Phosphorus inputs.[5]

Dead Zones

Dead zones across the world will likely increase as the world is continually dependent on fertilizers for industrial agriculture crops Global climate collapse has a high likely hood of worsening existing hypoxia zones and facilitating its formation in additional waters.[7]

Sources to begin with:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2212613914000373?via%3Dihub

https://academic.oup.com/icesjms/article/66/7/1528/656749

Climate Collapse

Land-Use Change

Corporations

See: Bayer-Monsanto | Syngenta

Sources

- ↑ https://branchoutnow.org/growing-sovereignty-turtle-island-and-the-future-of-food/

- ↑ Glibert, P.M. From hogs to HABs: impacts of industrial farming in the US on nitrogen and phosphorus and greenhouse gas pollution. Biogeochemistry 150, 139–180 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-020-00691-6

- ↑ Glibert, P.M. From hogs to HABs: impacts of industrial farming in the US on nitrogen and phosphorus and greenhouse gas pollution. Biogeochemistry 150, 139–180 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-020-00691-6

- ↑ Glibert, P.M. From hogs to HABs: impacts of industrial farming in the US on nitrogen and phosphorus and greenhouse gas pollution. Biogeochemistry 150, 139–180 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-020-00691-6

- ↑ Glibert, P.M. From hogs to HABs: impacts of industrial farming in the US on nitrogen and phosphorus and greenhouse gas pollution. Biogeochemistry 150, 139–180 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-020-00691-6

- ↑ https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/44677/aquatic-dead-zones

- ↑ Rabalais, N. N., Díaz, R. J., Levin, L. A., Turner, R. E., Gilbert, D., and Zhang, J.: Dynamics and distribution of natural and human-caused hypoxia, Biogeosciences, 7, 585–619, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-7-585-2010, 2010.