Qannabis

This page covers the more general aspects of the Qannabis plant family. For discussions of its implementation as climate strategy, see Hempurgy. To join in worldbuilding efforts, take a stroll through our Hempforest.

Definition

Historical

Past

Several scholars based on geography, evolutionary models, and historic data speculate that Cannabis originated already during the Pleistocene, millions of years ago. Paleobotanical studies attest that it was already present during the Holocene epoch about 11,700 years ago, more likely in the territories of Central Asia near Altai Mountains, where now the countries of Mongolia, Kazakhstan, and Siberia meet South Asia (near Himalaya and Hindu Kush Mountains) or East Asia. Subsequently, it has spread across Eurasia and all over the world, thanks to human domestication, well adapting to different climate conditions even the most unfavorable.[1]

Paleobotanical studies attest that cannabis was already present about 11 700 years ago in Central Asia near the Altai Mountains. South-East Asia has also been proposed as an alternative region for the primary domestication of cannabis.

Some 12,000 years ago, after the last glacial period, cannabis seeds followed the migration of nomadic peoples and commercial exchanges. This joint migration is an example of symbiosis comparable to the alliance of humans and canids.[2]

Present

Technical

Cannabis sativa is an annual plant of the family Cannabinaceae. It has erected stems which (depending on the environmental conditions and the genetic variety) can reach up to 5 meters.

The palmate leaves, usually composed of five to seven leaflets, are linear-lanceolate, tapering at both ends and the margins sharply serrate.

It is dioecious, but sometimes monoecious:

- Male flowers do not present petals, axillary or terminal panicles, have five yellowish tepals and five anthers.

- Female flowers germinate in the axils and terminally with one single-ovulate closely adherent perianth.

Moreover, C. sativa is rich in trichomes, epidermal glandular protuberances covering the leaves, bracts, and stems of the plant. These glandular trichomes enclose secondary metabolites as phytocannabinoids, responsible for the defence and interaction with herbivores and pests, and terpenoids, which generate the typical smell of the C. sativa. [3]

Soil

Stalk

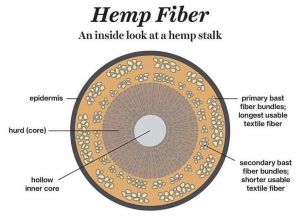

graphic: skin(bast(hurd/shiv(0))

The hemp bast is the soft, inner layer of the hemp plant's bark. It is used to make rope, twine, and fabric. The hurd is the woody core of the hemp plant. It is used to make paper, animal bedding, and composite wood products.

Seed

Flower

At least 538 natural compounds have been identified in C. sativa. Of these, more than 100 are identified as phytocannabinoids, because of the shared chemical structure. From a chemical point of view, phytocannabinoids have a lipid structure featuring alkylresorcinol and monoterpene moieties in their molecules. Moreover, they are mostly present in the resin secreted from the trichomes of female plants, while male leaves of C. sativa have few glandular trichomes that can produce small amounts of psychoactive molecules.

Over 200 Terpenoids, responsible for the fragrance of C. sativa, have been identified in the flower, leaves of the plant, and may represent 10% of the trichome contents . Limonene, myrcene, and pinene are most common and highly volatile. They are repellent to insects and act as antifeedants for grazing animals. The mixture of different C. sativa terpenoids and phytocannabinoid acids shows a synergistic mechano-chemical defensive strategy against many predators. The terpenoid production changes with environmental specific conditions. Indeed, as observed for the phytocannabinoids, terpenoids are produced as a defence mechanism: the amount of terpenoids increases with the light exposure (stressful condition for the plant) but decreases with soil fertility.[3]

Legality on Native Land

In December 2014 the first federal protections for state regulated Qannabis programs was passed by congress; Prohibiting the Department of Justice interfering with state Qannabis programs. The program would eventually expand to include territories and the District of Columbia. The lawmakers working behind the expansion did not take into account that Indigenous Nations are sovereign nations not territories. The Obama Department of Justice issued the Cole Memo[4] instructing U.S. attorneys to not enforce federal law on state-regulated Qannabis programs. The department of Interior matched the Cole Memo with another memo, the Wilkinson Memo[5], extending federal protections to Indigenous Nations.[6]

Picuris Pueblo Nation

In November of 2017 drug enforcement agents with the Bureau of Indian affairs entered the sovereign land of the Picuris Pueblo Nation and pulled up approximately twenty medical Qannabis plants. In December of 2021 agents would enter the sovereign land again pulling up nine medical Qannabis plants being grown at the home of a medical Qannabis patient.[7] The raids happened despite New Mexico legalizing medical Qannabis in 2007[8] and legalizing recreational use in 2021.[9]

Sources

- ↑ Pisanti + Bifulco 2018, "Medical Cannabis: A plurimillennial history of an evergreen" Journal of Cellular Pathology 2018; 234(6):8342-8351. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.27725

- ↑ Crocq 2020, "History of cannabis and the endocannabinoid system" Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2020; 22(3):223-228. https://doi:10.31887/DCNS.2020.22.3/mcrocq

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Bonini et al 2018 "Cannabis sativa: A comprehensive ethnopharmacological review of a medicinal plant with a long history." Journal of Ethnopharmacology Vol 227 (Dec 2018), pp. 300-315 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2018.09.004

- ↑ https://www.justice.gov/iso/opa/resources/3052013829132756857467.pdf

- ↑ https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/tribal/pages/attachments/2014/12/11/policystatementregardingmarijuanaissuesinindiancountry2.pdf

- ↑ https://www.politico.com/news/2022/04/05/tribes-marijuana-laws-00022899

- ↑ https://www.politico.com/news/2022/04/05/tribes-marijuana-laws-00022899

- ↑ https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-marijuana-idUSN0239750120070403

- ↑ https://apnews.com/article/legislature-michelle-lujan-grisham-recreational-marijuana-legislation-marijuana-61021fb6047fccfa09b004b30acf172d