Ka Pae Aina

"Ka Pae Aina (the Hawai’ian Archipelago) is made up of 137 islands, reefs and ledges stretching 2,451 kilometres southeast / northwest in the Pacific Ocean and covering a total of 16,640 square kilometres. The Kanaka Maoli, the Indigenous Peoples of Ka Pae Aina or Hawai’i, make up around 20% of the total population of 1.2 million. In 1893, the Government of Hawai’i, led by Queen Lili’uokalani, was illegally overthrown and a provisional government established without the consent of the Kanaka Maoli and in violation of international treaties and law. It was officially annexed by the United States and became the Territory of Hawaii in 1898. Hawaii acquired statehood in 1959 and became a part of the United States of America. The Kanaka Maoli continue to fight for self-determination and self-government and continue to suffer from past injustices and ongoing violations of their rights. Some members are involved in the Hawai’ian sovereignty movement, which considers the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawai’i in 1893 illegal, along with the subsequent annexation of Hawai’i by the United States. Among other things, the movement seeks free association with and/or independence from the United States."[1]

2023 Wildfire

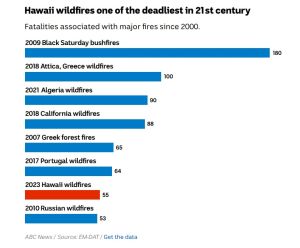

In August of 2023 a massive wildfire swept through the town of Lahaina[2][3][4][5] on the island of Maui. As of August 14, 2023 the death toll had reached 96 with around 1,000 people still missing.[6] Another fire had swept through West Maui on August 11th prompting an evacuation of the residents of Kaanapali, with a population of 1,100. In total, during the sime time frame as the Lahaina, there were six wildfires burning on the Big Island and Mauai.[7] Residents of Lahaina were not warned before the wildfires swept through the town. There were no emergency sirens and many residents questioned why there was not sufficient warning if any at all.[8] The fire was the worst in Ka Pae Aina's history and is in the top ten deadliest fires of the 21st century according to the 'International Disaster Database'.[9] The fire is the deadliest wildfire in over a century in the so-called United States.[10]

Causes

Na Wai `Eha

The Na Wai' Eha or 'The Four Great Waters' are fresh water streams that helped sustain thriving communities since time immemorial. For over a century these streams have been diverted to irrigate sugar plantations. The major water diverter is the 'Wailuku Sugar Company,' but they no longer produce sugar cane. Wailuku Sugar Company has now been selling off land to private developers and continue to divert the water to sell the private developers.

... Wailuku Sugar Company has reinvented itself as Wailuku Water Company. It maintains its water diversions to turn a profit by selling that water to the private development projects built on the former plantation lands. Wailuku hoards the “surplus” that it hopes to sell to future developments by giving it in the meantime to Hawaiian Commercial & Sugar, which uses the water as a cheap alternative to its non-potable agricultural wells, or dumps it on sandy fields it wouldn’t otherwise farm. But the water isn’t the companies’ to sell or to waste.

Water in Hawai`i is a public trust resource, protected by the Hawai`i Constitution for the benefit of all Hawai`i’s people. The state has a duty to protect and restore traditional and customary Hawaiian practices, ecological uses, recreation, scenic values, and many other public uses of flowing stream water. Protecting private water banking and profiteering is not one of the state’s responsibilities—restoring Na Wai `Eha is.[11]

Maui residents depend upon the Na Wai 'Eha stream flows to recharge the ground water supply; More than half of residents depend this ground water:

... Native stream animals, wetlands, estuaries, and nearshore fisheries need a continuous supply of fresh water in order to remain healthy and functional. Streams need flow to support swimming, fishing, nature study, and aesthetic enjoyment.

And local communities need cool, flowing stream water for traditional wetland kalo (taro) cultivation, the staple food of the traditional Native Hawaiian diet. At one time, Na Wai `Eha supported Maui’s political center and fed the largest continuous area of wetland kalo fields in the Hawaiian Islands.

When companies began diverting streamflow for their sugar crops, kalo cultivation by Native Hawaiian communities suffered. Community members continue to cultivate some kalo where they can, but the streams of Na Wai `Eha must be restored to revive this important cultural tradition to its full potential. Flowing streams will also provide habitat for native stream species and reinvigorate traditional and customary practices, including subsistence gathering.[12]

Occupation

Kaniela Ing, a seventh generation Kanaka Maoli (Native Hawaiian,) was interviewed on 'Democracy Now!' following the fires, and rhetorically asked:

But what I am wondering, personally, is, once the recovery efforts start to unfold and the cameras are gone, who’s going to be left more powerful or less powerful? Are people still going to be paying attention when the recovery work is going to last for years? And is that going to make community members stronger, or is it going to make the people who have mismanaged the land and water and created the conditions for these fires to happen even more powerful?[13]

Climate Collapse

... So there’s two facets to this. First is climate change. The National Weather Service says the cause of this fire was a downed power line, and the spread because of hurricane-force winds. And the spread was caused by dry vegetation and low humidity. Those are all functions of climate change. This isn’t disputable. This isn’t political. It, unfortunately, has become politicized, but it’s a matter of fact. Climate pollution, corporate polluters that set a blanket of pollution in the air that is overheating our planet contributed — caused the conditions that led to this fire.

In addition, there is mismanagement of land. The original “Big Five” [Castle & Cooke, Alexander & Baldwin, C. Brewer & Co., American Factors (now Amfac), and Theo H. Davies & Co.] oligarchy in Hawaii, missionary families that took over our economy and government, they continue on today as some of our largest political donors and landowners and corporations. They’ve been grabbing land and diverting water away from this area for a very long time now, for generations. And Lahaina was actually a wetland. You could take a — like, Waiola Church, you could have boats circulating the church back in the day. But, you know, because they needed water for their corporate ventures, like golf courses and hotels and monocropping, that has ended. So the natural form of Lahaina would have never caught on fire. These disasters are anything but natural.[14]

Climate collapse acts as a threat multiplier for any natural disaster that may occur exacerbating already dangerous conditions. The fire in Maui is an example of how seemingly disparate elements of weather come together to create a deadly disaster.[15] Climate collapse contributed to grasses drying out causing a deadly tinder box, a drought, multiple wind effects, and increases in size & frequency of Hurricanes:

... climate change acts as a "threat multiplier," increasing each individual risk and exacerbating them if and when they collide, said Katharine Hayhoe, an atmospheric scientist and chief scientist at The Nature Conservancy.

“Every extreme event today is occurring over a background of an altered climate,” she said.

For instance, warmer-than-usual oceans can fuel the formation of bigger and stronger hurricanes. Higher temperatures from global warming also make droughts more frequent and intense, and dry vegetation, including non-native grasses and shrubs, burn quickly and provide dangerous fuel for wildfires.

“And then on top of that — the icing on the cake or the straw on the camel’s back, so to speak — you have climate change,” Hayhoe said. “It’s a threat multiplier, an exacerbator, an amplifier.[16]

Loss of Native Vegetation

Historically fire is not believed to have played a large role in the evolution of Ka Pae Aina's islands. Fires have become more frequent on the islands in part from invasive grasses replacing native forests and other native grasses; as a result many native species are not capable of adapting or even recovering from increasing frequency and size of wildfires.[17]

... Once a fire does inevitably occur, the post-fire plant community is typically characterized by rapid non-native grass regeneration, which then predisposes these ecosystems to more frequent and higher intensity fires. This cycle of non-native grass invasion, fire and grass reinvasion (i.e. the invasive grass–widlfire cycle) is a common occurrence in tropical ecosystems that is thought to lead to large-scale land-cover change.[17]

Fire Scientist Clay Trauernicht makes the connection between the loss of native vegetation and the Lahaina wildfire on 'Democracy Now!' explaining:

...the reason that they’re having the effects they are is because of the landscape-scale changes that your prior guests were mentioning. And that’s the change in the vegetation surrounding the community in Lahaina, as well as the community Upcountry Maui, which is experiencing similar fires, and which are still burning right now. And these are changes that have affected most of the island in the state, in the sense that these change in land use over the past couple decades, the decline in agricultural production, has really resulted in the dramatic expansion of these non-native tropical grasses. And this really creates this vulnerability that we’re seeing right now and, you know, the really explosive growth in fire that we saw over the past couple days.[18]

26 percent of the Hawaiian islands are invaded by non-native grasses. When the grasses burn there is a high likely hood of them spreading to native forests and after the forests are burned the invasive grasses proliferate in the burned areas. During the wet season in Ka Pae Aina wet conditions can spur invasive grasses to grow as quickly as 6 inches a day and reach up to 10 feet tall. As these grasses dry they become tinder for wildfires.[19]

Cattle Grazing

Megathyrsus maximus [Jacq.], previously Panicum maximum and Urochloa maxima [Jacq.], an African bunchgrass, was introduced to Hawaii for cattle forage and became naturalized in the islands by 1871. As in other tropical ecosystems, M. maximus quickly became problematic because it is adapted to a wide range of ecosystems (e.g. dry to mesic) where it alters flammability by dramatically increasing fuel loads and fuel continuity. Year-round high fine fuel loads with a dense layer of standing and fallen dead biomass maintain a significant fire risk throughout the year. Because M. maximus recovers quickly following disturbance (i.e. fire, ungulate grazing, land-use change, etc.) and is competitively superior to native species, many areas of Hawaii, as well as throughout the tropics, are now dominated by this non-native invasive grass.[17]

Increasing Wildfire Prominence

Wildfires have been increasing in frequency and severity in Ka Pae Aina. in 2021 there was a 60-plus-square-mile fire on the Big Island and in 2018 there were another series of fires in Maui and Oahu that destroyed 21 buildings. These fires are greatly exacerbated by invasive grasses.[20] A study published in 2020 by the 'American Meteorological Society' concluded that 85 percent of the land burned during three of the 2018 wildfires were invasive grasses.[21]

Drought

During the time of the Lahanai wildfire more than 80 percent of Hawaii was abnormally dry with 15 percent in a moderate drought and around 3 percent in a sever drought.[20]

Hawaii has been especially dry in recent months, with 100% of the state in a drought at 2 points over the past year, and more than 95% of the state considered abnormally dry or in a drought at this time last year—well above the islands’ typical drought level during the month of August, which has ranged between 11.5% and just over 68% considered abnormally dry or in drought since 2015.[20]

Flash Droughts

Climate collapse has been making 'Flash Droughts', rapid onset drought conditions, far more regular. In Maui this was the case and one of the multiple factors which contributed to the devastating wildfire.[19]

Flash droughts are so dry and hot that the air literally sucks moisture out of the ground and plants in a vicious cycle of hotter-and-drier that often leads to wildfires. And Hawaii’s situation is a textbook case, two scientists told The Associated Press.

As of May 23, none of Maui was unusually dry; by the following week it was more than half abnormally dry. By June 13 it was two-thirds either abnormally dry or in moderate drought. And this week about 83% of the island is either abnormally dry or in moderate or severe drought, according to the U.S. drought monitor.

Maui experienced a two-category increase in drought severity in just three weeks from May to June, with that rapid intensification fitting the definition of a flash drought, said Jason Otkin, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Wisconsin, Madison.[19]

Down-Slope Wind

... it was how those strong winds interacted with Maui’s mountainous topography that created such volatile fire conditions in the town of Lahaina, she said.

The effect is known as downslope wind. As wind passes over a mountain and comes down the other side, it becomes compressed under extremely high pressure, making it both super dry and super hot, Kolden said.

“What that meant was that any place where the winds were aligned and there was this downslope wind, they had the strongest, the driest and the hottest winds associated with this larger hurricane wind event,” she said.

Wind gusts up to 67 mph were reported in some spots in Maui, enabling fires to move quickly over the landscape.[22]

Foehn Wind Effect

In studying the satellite feeds, Mr McRae says he noticed similarities to the conditions causing Australia's Black Summer bushfires in 2019-20.

He says the wildfires in Hawaii are likely being driven by a specific type of wind — called a Foehn wind — that traps the heat close to the ground.

"When you've got a hot fire, it heats a lot of air that wants to go upwards," he told the ABC.

But when there is a Foehn wind in effect, "the flames aren't rising up into the upper air and all these burning embers are bouncing around [close to the ground]."

Although it's still early days, he says, "it's the classic set-up when people start jumping into the ocean to escape fires" — something that's reportedly been happening in Hawaii.

According to Mr McRae and his UNSW colleagues' research, about 50 per cent of the fire activity north of Sydney during the Black Summer fires were due to this effect.

"It's become a big ticket item here," he said. "There are a lot of parts of the world where the dominant type of fire is changing."

Mr McRae says it's too early to tell, but this might have just started happening in Hawaii.[23]

The Big Five

The Great Hawai'i' Sugar Strike was launched against the Hawaiian Sugar Planters' Association and the “Big Five” companies in 1946. The “Big Five” were made up of a handful of corporate elite companies: Alexander & Baldwin, American Factors, Castle & Cooke, C. Brewer, and Theo. Davies. They exercised complete control over Hawai'i's sugar plantation workers and the majority of the island’s multi-ethnic workforces.

In order to combat these companies and the plantation owners who followed the industry’s minimally suitable working conditions, an activist from California, Harry Kamoku organized the first multi-racial union: the Hilo Longshoreman's Association. In 1937, this union joined the California based International Longshoreman's and Warehousemen's Union (ILWU) and created its headquarters in Hawai'i'.

Jack Hall, director of the ILWU from 1935-46, recruited people from all racial groups and organizations to compete with the industry’s tactic of keeping racial groups separate, which hindered discussion around comparing wages and creating unions between racial groups. ILWU had four goals that would lead to better wages and working conditions: they proposed worker earn 65 cents per hour, have 40-hour workweeks, have a union shop, and have the ability to convert perquisites to cash.

The union shop would require all workers to become a part of a union once hired by the plantation owners. Owners provided free perquisites, such as medical care, housing, fuel, and utilities, to workers and their families. ILWU sought to change these to a paid basis so that sugar planters could not continue to easily control the lives of their workers. The Big Five and the plantation owners did not find these demands to be fair and they refused to negotiate with the ILWU and the workers.

In response to this refusal, the sugar workers began the first industry-wide strike conducted in Hawai'i'. Under the leadership of the ILWU, about 26,000 sugar workers and their families, 76,000 people in all, began a 79-day strike on 1 September 1946 that completely shut down 33 of the 34 sugar plantations in the islands. For the safety of the workers during the strike, the ILWU negotiated with plantation owners so that no workers could be evicted from their industry-provided homes. They also ensured the plantation owners that all essential workers would remain on their jobs, such as sanitation and power workers[24]

Interracial Labor Movement

Princess Ka’iulani

As a royal woman in the late nineteenth century, Ka’iulani was subject to constant surveillance by the global press, in Hawai’i, on the U.S. continent, and across Europe. Ka’iulani was known around the world for her intelligence and attractiveness; American newspapers consistently ran stories about her—or rather, her looks. On March 2, 1893, the San Francisco Morning Call described her as a “beautiful young woman of sweet face and slender figure,” remarking on her dark skin and soft eyes, which are “common” among the Hawaiians. While this was a typical characterization of her, other descriptions seemed to be shocked by her “intelligence,” attributing her education to her royal status and her father’s Scottish bloodline, instead of a valued Kanaka characteristic. In an interview with the Morning Call shortly after Ka’iulani’s death, Colonel Macfarlane, a close family friend, described her as having the dignity of an English aristocrat and the grace of a creole. He describes her as a “pure half-caste,” explaining that her early seclusion from other Hawaiians and English schooling made her thoroughly English in her manners and ambitions, with no trace of “native superstition” left. Macfarlane attributes Ka’iulani’s civilized and dignified demeanor to her Englishness and her colonial training, in spite of her Nativeness. Although seemingly intended as a compliment, Macfarlane’s own perceptions reflect the racial logics of the time...

...As an emergent head of state, Ka’iulani carried her kuleana (responsibility) boldly, protesting the overthrow of the kingdom by writing letters to American newspapers, taking on Lorrin A. Thurston, one of the architects of the overthrow. She accused him of conspiring to keep her away from Hawai’i so that he and other annexationists could steal the throne. Ka’iulani and her contemporaries all fought to save the kingdom. They were responsible for the anti-annexation petitions that are today known as the Kūʻē Petitions. These wahine koa (women warriors) traveled from island to island and village to village collecting signatures from Kanaka Maoli (and non-Kanaka subjects of the Hawaiian Kingdom) who were opposed to annexation. Mainstream history fails to document the resistance of Kanaka Maoli, who organized 38,000 signatures opposing annexation, and that women were responsible for much of this resistance. Women like Emma Nāwahī and Abigail Kuaihelani Campbell of Aloha ʻĀina o Na Wahine (Hawaiian Women’s Patriotic League) rejected Western social conventions that said women should stay home and out of politics. They were key figures in Hawaiian resistance. The erasure of this history represents the ways in which Hawaiian women’s labor, their politically astute activism, and their loyalty to lahui is rendered invisible in history and occluded by hotels, hula competitions, and even street names. These events and signs are hauntings of what was and a future that could have been. They are mnemonic devices that remind us of the story of women’s organizing. The emphasis on Ka’iulani marks ongoing non-Hawaiian fascination with images of Hawaiian women and stories about Hawai’i, but these non-Hawaiians are not interested in Hawai’i’s complex political history.

... Rather than focusing solely on our past, as tourism constantly encourages us to do (especially when talking about the kingdom or ali'i), remembering our ali'i is part of our shared sense of self; it is how we know who we are, and it is built into every understanding of what it means to be Kanaka Maoli. We refuse to be ghosts, but we still haunt. While the outside world tells us (Hawai'i and Hawaiians) that we are just their playground, a sexy culture, a military landing, and staging site, Ka'iulani's memory haunts all of us, reminding Kanaka Maoli that we were a royal, civilized people whose love for our nation never died. The story of Princess Ka'iulani is haunted by ghosts, memory, history, fears, and desires for control over the meaning of the past and how it informs the future. The curated history packaged for tourists will not disrupt thier vacation in paradise. But as all hauntings go, the spirit of the past reminds people that something is wrong, amiss, unfinished. That unsettling feeling reminds us in the present that the past remains a terrain of contestation. The sovereignty of the Hawaiian Kingdom lives and ka lahui Hawai'i persists.[25]

Ahupua'a System

Expand this section--- alternative to private property/ capitalism/ land management-- **important**

https://www.nationofhawaii.org/ahupuaa/

https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20220818-ahupuaa-hawaiis-ancient-land-management-system

Private Property

The idea of buying and selling land didn’t really come into being in Hawaiʻi until the mid-nineteenth century. “The single most critical dismemberment of Hawaiian society,” explains Native Hawaiian historian Jonathan Kay Kamakawiwoʻole Osorio, “was the Mahele, or the division of lands and the consequent transformation of the ʻāina [land] into private property between 1845 and 1850.” Private property rights not only led to the sale of land but also changed the political balance of power in the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi, as land ownership gave non-Natives greater influence on the politics of the day. Plantations require vast acreage, and U.S. imperialism proved the way to secure that land. By 1893, Queen Liliʻuokalani was overthrown by the white oligarchy, many of whom were heavily invested in the sugar industry, with backing from James Dole’s older cousin, Sanford Dole, who became the first territorial governor when the U.S. annexed the islands in 1898.[26]

Military Occupation

Kaho'olawe Test Bombings

After the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, the United States declared martial law on Ka Pae Aina. In May of 1941, the US Army leased a small section of Kaho’olawe from cattle ranchers for $1.00 a year[27]; Kaho'olawe, an island held sacred by The Kanaka Maoli, was then confiscated and turned into a US air-force test bombing site.[28] "In ancient times, the sacred island of Kaho’olawe was, according to local tradition, the Hawaiian peoples’ center for celestial navigation, a bountiful fishing grounds, and a spot where native priests carried out cultural and religious rites. In the modern era, the 45 square-mile area has been dubbed “the most shot island in the world.”"[29]

Even before war converted Kaho’olawe into the Pacific’s target range, visitors and residents had already ensured the island was well on its way to ruin. The abasement started when goats were introduced in 1793. Already sweltering in Maui’s rain shadow, much of Kaho’olawe’s heartiest vegetation disappeared due to the animals. In 1832, the island became the home of a penal colony. By 1858, official leases to ranching companies allowed sheep, cattle, and even more goats to roam and gobble, leading to severe erosion and soil loss. Rats and feral cats followed the people and livestock, quickly overpowering the natural fauna. Non-native trees, grasses, and shrubs brought in as feed further skewed the island’s natural balance.[30]

In 1965 Operation Sailor Hats was conducted on the island and consisted of three detonations with 500 tons of TNT being detonated to simulate the blast effects of nuclear weapons on shipboard weapon systems.[31]

"We had to save the island," said activist Walter Ritte.

In 1976, Ritte and other members of the Protect Kahoolawe Ohana began a series of occupations on the island, risking arrest or death as they tried to stop the bombing. Two men, George Helm and Kimo Mitchell, were lost at sea while returning from a trip to Kahoolawe.

"It was a huge story," said Nainoa Thompson, president of the Polynesian Voyaging Society. "They would take on the whole federal government, the military, the Navy. Yikes.

"And the federal government and the Navy couldn't do anything because they are willing to give up everything. They weren't compromising. And that whole statement was revolutionary for everyone that wanted to see that there was some justice to the native people in their own homeland."

Ritte said it was not only the cries for help from the Hawaiian people that drove them back to the island, but the cries from the land.

"It was some kind of an experience, but when I was looking at this rock and the (military) helicopter went straight up and I was just fixed on that rock and then the rock became the whole island. And I felt this tingling coming into my body and … I kind of lost it, I mean, I couldn't remember too much but I knew that island was going to die," he said...

...Some traveled to Washington D.C. to meet with the president, while thousands of others wrote to local politicians and met with the media. Meanwhile, Ritte and Richard Sawyer would stay on the island for the longest occupation — 35 days..

"We had to eat coconuts from the beach and pound eels with the rock to kill the eel and eat the eel," Ritte said. "We even had to start eating baby goats and stuff just to survive."

Military personnel were sent out to search for the two — each time finding no sign of them.

"Richard and I ducked for cover … and the ground was shaking and bombs were dropping. Our wives kept telling them they're on the island, they're on the island," Ritte said. "And the senators gave the OK — it's all clear start bombing. We could've been blown up."

"It changed my whole life. From that day."[32]

Protect Kahoolawe Ohana sued the United States military after the occupation and the bombing was eventually ordered to end; In 1993 congress voted to end all military usage of the island and transfer the island back to the state of Hawaii. Despite the military being officially ordered to cease all operations on Kaho'olawe the damage had already been done and the island was littered with bomb debris and unexploded ordnance. Since the transfer, more than 9 million pounds of unexploded ordnance and other remnants have been cleared from the island. [33]

Red Hill Bulk Fuel Storage Facility

On January, 13th 2014 27,000 gallons of jet fuel leaked from the storage tanks at the US Air Force's Red Hills Fuel Storage Facility in Moanalua.[34] The storage tanks at this cite are the biggest of their kind in the so called United States and sit only 100 feet above one of Oʻahu's main aquifers. The fuel tank leaks continue to this day, in part because the storage containers are old and small holes were found and claimed as the cause of the leak,[35] additionally there has been petroleum found in water sources.[36] [37]

On May 6th, 2021 another leak occurred at the Red Hills Fuel Storage Facility releasing 19,000 gallons of JP-5 jet fuel into other storage containers causing pressure buildup in neighboring fuel lines. The spilled fuel remained in the other pipeline for six months before rupturing and spilling fuel into the tunnel system near the Red Hill drinking water system shaft.[38] Residents were still feeling side effects resulting from contaminated water a year later according to a survey conducted, but the actual number of effected residents was likely underestimated. 80% of respondents to the survey, 788 people, reported symptoms in the last 30 days such as headaches, skin irritation, fatigue and difficulty sleeping. Of those who were pregnant during the crisis, 72% experienced complications.[39] The Navy has pumped and dumped over a billion gallons of water from Oahu’s primary aquifer in an effort to clean up the fuel contamination and has assured residents that the drinking water is safe despite continued reports of people feeling side effects after ingesting water.[40]

"Though the Pentagon has committed to shutting down the Red Hill fuel tanks within two years... A report released in June 2022 states that the U.S. Navy was negligent in the maintenance of the fuel tanks, resulting in (preventable) leaks. The U.S. Navy has begun to defuel some pipelines but is proposing to have the fuel tanks closed by 2027 and to stay in place for potential use in the future."[41] [42]

Forever Chemicals

The EPA and state Health Department said in a letter to the Navy that PFAS ― known as forever chemicals ― were detected in groundwater samples on Dec. 20 and 27, 2021 relating to fuel leakages at the Red Hill military fuel storage site.[43] Hawaii News Now reported about the contamination of groundwater before the letter- [44] The reporting came after some 1,300 gallons of AFFF concentrate was spilled inside a tunnel at the Navy’s underground Red Hill fuel facility on Nov. 29 2022[45]

Aqueous film forming foam, also known as AFFF, was released on the upper end of the facility into the aboveground soil and into the underground facility, the health department said in a news release. AFFF is used to suppress fuel fires and contains chemicals known as PFAS that are linked to cancer and other health problems. PFAS chemicals are notorious environmental contaminants because they are “forever chemicals” that don’t break down in the environment.[46]

Experimental Biotechnology

Since the early 1990's over 3,300 permits have been issued for testing genetically engineered crops.[47]

Papayas

Genetically modified Papaya plants dominate the industry in Ka Pae Aina after being introduced in an attempt to combat the Papaya ringspot virus, which was decimating crops across Hawaii.[48]

Syngenta

According to Syngenta's website they "... invest and innovate to transform the way crops are grown and protected to bring about positive, lasting change in agriculture. We help farmers manage a complex set of challenges from nature and society. Our approach is to ensure that everybody wins: that farmers are prosperous, agriculture becomes more sustainable, and consumers have safe, healthy and nutritious food."[49]

Syngenta's method of achieving these, seemingly, noble goals is by wantonly spraying toxic pesticides and insecticides over crops to test their resistance to the chemicals and as a result the Ka Pae Aina's Native residents have been poisoned enmasse by these loosely regulated experiments. Residents have described the test sites as releasing large red dust clouds into the air covering their houses and cars with a thin layer of red- especially during periods of high winds. Because the island is able to grow food year round these types of experiments, involving mass chemical spraying of crops, also occur year round.[50] The mass testing of toxic chemicals has caused residents to dub Waimea, located on the island of Kauai, where much of Syngenta's spraying took place, "Poison Valley." [51]

2016 Lawsuit

In 2016 Syngenta sprayed a pesticide on one of its farms in Kekaha, Kauai, containing chlorpyrifos, over genetically modified corn crops. According to EPA regulations after spraying chlorpyrifos it is required to wait 24 hours before sending workers into the field or require workers to wear protective gear, but Syngenta did neither sending 19 workers into the contaminated fields. Syngenta allegedly did not realize what had happened and after realizing isolated and decontaminated 35 workers- the EPA deemed the decontamination efforts were insufficient. 10 of the workers were eventually sent to the hospital, due to chemical exposure, with three staying over night, which the EPA also deemed to be insufficient due to Syngenta's lack of urgency [52] [53]

In 2017 another incident occurred when Syngenta sprayed the same chemical over fields and did not properly post warning signs indicating there was poison covering the crops. Five crews containing 42 employees were potentially exposed to the toxic chemical and at least one worker displayed symptoms of pesticide poisoning. After the incidents the EPA filed a lawsuit against Syngenta on behalf of the affected workers. "The result of oversights allegedly affecting as many as 77 workers — involving multiple failures to warn, properly post signs and the like — led to a 388-count complaint. With maximum penalties as high as $19,000 per violation, Syngenta faced potentially millions of dollars in fines."[54]

Instead of the proposed 4.8 million dollars the EPA was seeking in damages, based on the 2016 incident alone, Syngenta and the EPA reached a settlement agreement of 400 thousand dollars to pay for 11 worker protection training sessions for growers and an additional 150 thousand dollar civil penalty. The agreement was about 3 percent of what the EPA originally announced it was seeking.[55]

In response, Alexis Strauss, a regional administrator of the EPA, stated: “You don’t get to settle with a company by getting the maximum amount for every violation.”[56]

Hartung Brothers Inc.

In 2017 Hartung Brothers Inc. completed an acquisition of Syngenta Seeds Hawaii Operations and acts as a contractor for all Syngenta related activites.[57] Ed Attema, Syngenta head of Global Seed Operations, Production & Supply, stated, in regards to the acquisition of their land on Oahu and Kauai, “We are extremely pleased to have this agreement with Hartung Brothers for our Hawaii sites. The goal has been to have our employee talent base and facilities maintained and to contract work with the new owner, and that will be achieved.”[58]

On the Hartung Brothers Inc. website it explains how they are continuing Syngentas legacy of dangerous experimental GMO testing/ research and development: "Our seed research and development operations in Hawaii, enables us to offer end-to-end turn-key services, including: contract R&D service to customer genetics and protocols, foundation seed production, pilot hybrids, and hybrid production, processing, warehousing, and distribution."[59]

Bayer-Monsanto

Mokulele farm

Bayer-Monsanto's Mokulele farm tests new strains of genetically modified corn seed and sprays pesticides/ insecticides on the crops.[60]

2014 Lawsuit

"In a plea agreement submitted to the Honolulu district court on November 21 [2019], Monsanto-Bayer pleaded guilty to illegally spraying one of the world’s most toxic pesticides, Methyl Parathion, in Maui in 2014, six months after the US Environmental Protection Agency banned it. In addition, the company admitted to using the pesticide in a manner that endangered the lives of the field workers who did the spraying. It was also found guilty of illegally storing, transporting and disposing of the chemical after the ban."[61]

As a result of the guilty plea Monsanto-Bayer was ordered to pay 6.2 million dollars in criminal fines and an additional 4 million in community service payments. "The proposal, however, did not impose personal fines or prison sentences on any Monsanto employees."[62]

2020 Lawsuit

Monsanto was charged with 30 environmental crimes after letting workers go into corn crops that had been sprayed with a chemical named Forfeit 280 and for illegally storing certain agriculture chemicals on Maui and Molokai. Federal law states 6 days must passed after spraying the chemical before anyone is allowed to enter the area.[63]

Waimea Valley

Waimea Valley, before industrial agriculture and mass GMO/pesticide experimentation flooded the area, was a self sustainable town where many people practiced sustainable methods of agriculture.[64]

University of Hawaii

Since 1968, the University of Hawai’i (UH) has rented Mauna Kea’s summit for a dollar per year through a sixty-five-year lease from the state of Hawai’i. Initial approval was to build one observatory, but within two decades seven telescopes had been erected and the giant twin Keck Observatory was under construction. In what is known as the Astronomy Precinct of the Mauna Kea Science Reserve, twenty-one telescopes are somehow counted as thirteen “observatories.” … [65]

Thirty Meter Telescope

… A 2005 follow-up to a 1998 legislative audit found that, for thirty years, management by UH [University of Hawai’i] was “inadequate to ensure the protection of natural resources,” controls were “late and weakly implemented,” historic preservation was “neglected,” and the “cultural value of Mauna Kea was largely unrecognized.” UH was in danger of losing allies and sought to remake itself as a reformed caretaker. Acknowledging but yet downplaying a series of well-documented failures, UH assumed a mantle of “cultural sensitivity.” It “recommitted to inclusivity” and promised “to do the TMT [Thirty Meter Telescope] the right way.” UH and astronomers now suggested they were honoring Native Hawaiian traditions of ocean voyaging, star-based navigation, exploration, and discovery. Like “ancient Hawaiians,” they suggest, “modern astronomers” also share feelings of wonder and skill in studying the heavens – like “brothers and sisters.” Not only was there an assumption that Native land should remain accessible to Western science, but even Native culture, history, and language were theirs for the taking. One thing TMT advocates fail to acknowledge, however, is the debt they owe to imperialism. Seldom do they account for the legacies of settler colonialism that rendered Native lands available to scientific tourism in the first place. Rather than turning over a new leaf, this seeming transformation is a move to settler innocence where astronomers, administrators, and TMT advocates imagine themselves as inheritors of Native traditions or heirs to Indigenous lands at the same time they cry victimhood. In the cause of Mauna a Wakea, the idealized image of a Hawaiian as hospitable or compliant is welcome, but actual Hawaiians, those who think and protest, are not.[66]

...The telescope controversy signals a new stage in the Hawaiian movement. Argued to be the next “world’s biggest telescope,” the so-called Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT) would be astronomers’ latest monument to Western scientific achievement. As the state talks of “progress” in its support for the TMT, it is borrowing from science its cultural authority as a voice of reason. The value of science to the state is the ideological substance it provides in justifying schemes to profit from land as a resource – one to be packaged, sold, and developed. In this sense, the struggle is about more than a telescope. It is about settler legitimacy, possession, and absolution from the guilt derived from accepting the spoils of U.S. imperialism in the Pacific. This struggle is about how we relate to land and water and to each other. It is about power and control.[67]

Tourism

Tourism in Ka Pae Aina is a dominant sector of the state accounting for 21 percent of its economy.[68] "In 2017 alone, according to state government data, there were over 9.4 million visitors to the Hawaiian Islands with expenditures of over $16 billion."[69] Detours: A Decolonial Guide to Hawai'i, edited by Hokulani K. Aikau and Vernadette Vicuña Gonzalez[70] is a collections of essays by various authors deconstructing the false idea of Ka Pae Aina being a pristine paradise for tourists to exploit and consume. The first two paragraphs of the introduction read:

Many people first encounter Hawai’i through their imagination. A postcard imaginary of the Hawai’ian Islands is steeped in a history of discovery, from the unfortunate Captain Cook, to the missionaries who followed, the military that rests and re-creates, and the hordes of tourists arriving with every flight. Travel writing, followed by photography and movies, have shaped the way Hawai’i is perceived. Guidebooks are one of the most popular genres depicting the islands. They offer up Hawai’i for easy consumption, tantalizingly reveal its secrets, and suggest the most efficient ways to make the most of one’s holiday. Tour guides are part of the machinery of tourism that has come to define Hawai’i. Residents and visitors alike are inundated with the notion of Hawai’i’s “aloha spirit,” which supposedly makes Hawai’i paradise on earth. Hawai’i’s economy revolves around tourism and the tropical image that beckons so many. This dominant sector of the economy has a heavy influence on the social and political values of many of Hawai’i’s residents.

We titled this book ‘’’Detours’’’ because it is meant to redirect you from the fantasy of Hawai’i as a tropical paradise toward an engagement with Hawai’i that is pono (just, fitting.) Hawai’i, like many places that have been deemed tourist destinations, is so much more than how the guidebooks depict it – a series of “must-do” and “must-see” attractions; a list of the most accommodating, affordable restaurants and hotels; beaches and forest trails waiting to be discovered; a reputation as a multicultural paradise adding color to a holiday experience; and a geography and climate marshalled for the pleasure of visitors. While this place is indeed beautiful, it is not an exotic postcard or a tropical playground with happy hosts. People here struggle with the problems brought about by colonialism, military occupation, tourism, food insecurity, high costs of living, and the effects of a changing climate. This book is a guide to Hawai’i that does not put tourist desires at the center. It will not help people find paradise. It does not offer solace in a multicultural Eden where difference is dressed in aloha shirts and grass skirts. This book is meant to unsettle and disquiet, and to disturb the “fact” of Hawai’i as a place for tourists. It is intended to guide readers toward practices that disrupt tourist paradise.[71]

Larry Ellison

In 2012 Larry Ellison purchased the island of Lanai, of Ka Pae Aina, including most businesses and housing for 300 million dollars.[72] The purchase of the island included:

... 98 percent of the island, including the two Four Seasons resorts and their championship golf courses, the more modest Hotel Lānaʻi, the majority of the luxury homes, and all of the employee cottages. In essence, most of the accommodations on the island are under his control, along with the gas station, the car rental agency, the supermarket, Lānaʻi City Grille, a solar farm, and all the buildings that house the small shops and cafes in Lānaʻi City. He owns 88,000 acres of former pineapple fields and 50 miles of beaches—but technically, in Hawai‘i, no one, with the exception of the U.S. military, is supposed to own beaches or control beach access....[73]

Ellison claims that his motives for purchasing the island and the majority of its businesses/ housing are rooted in creating a sustainable island. What this means for the Native Peoples of Ka Pae Aina and Ellison are likely not the same thing.

It is one thing to own an uninhabited island; it is a different thing altogether to purchase an island, as Ellison has, on which lives a sizable group of permanent residents with far longer connections (including genealogical ones, for many) to the land than the landlord has. For over a century, the lives and livelihoods of the residents of Lana'i have been tied to the destinies of a succession of white landowners with the resources to change not just the economy but also the geographical terrain of the island in the hope of achieving their singular vision of making the island "profitable."...[74]

Food Sovereignty

See: Food Sovereignty

Decolonization

This book is important for at least two reasons. First, it affirms that the ala loa—the long path—of decolonization is one worth following, and that anyone with a commitment to do the work can walk this path. Second, the contributors and their work remind us that we are all following in the footsteps of people who came before us and that we are moving the cause forward in diverse ways according to our individual gifts, relationships, perspectives, and efforts. This is important because just as colonization, capitalism, and heteropatriarchy continue to evolve and shape-shift, appropriating our efforts, co-opting our people, and slowly killing us, we need decolonizing practices that are creative, adaptive, innovative, and ongoing if Indigenous peoples are going to get out in front of the colonizing machines and hold firm to “the chattering winds of hope.”

We intentionally use the words decolonize and decolonial to identify the main goal of this book: to restore the ea of Hawaiʻi. Kanaka ʻŌiwi scholar and activist Noelani Goodyear-Kaʻōpua describes “ea as both a concept and a diverse set of practices. . . . Ea refers to political in dependence and is often translated as ʻsovereignty.’ It also carries the meaning of ‘life’ and ‘breath,’ among other things. . . . Ea is based on the experiences of people on the land, relationships forged through the process of remembering and caring for wahi pana, storied places . . . Ea is an active state of being . . . Ea cannot be achieved or possessed; it requires constant action day after day, generation after generation.”3 Ea is a political orientation and a set of intentional practices that must be done day after day, generation after generation. During ka wā ʻOiwi walo nō (the era that was indeed Native), ea was the way of life. Ea was for kanaka as water is for fish. It is the air we breathe.4 Today, ea must be cultivated by Kanaka and non-Kanaka alike if it is going to persist into the future.

To be sure, resistance and decolonization, the companions of ea, have been around since Europeans “discovered” lands and people on far-distant shores and exerted control over the natural and human resources they found: colonization sparked decolonization. European exploration marked the dawn of an age of imperialism and colonialism —the process of creating European settlements in colonial outposts in order to assert direct control over land, labor, markets, resources, and the flow of capital, commodities, and ideas. Settler colonialism is the particular form colonialism has taken in places such as the United States, Canada, Aotearoa/New Zealand, and Australia. Settler colonialism describes the process by which settlers came, stayed, and formed new governmental structures, laws, and ideas intended to affirm their ownership of land and labor. These global shifts also marked

the emergence of resistance to empire and colonization. Decolonization describes material practices that have arisen in response to the myriad forms imperialism and colonization have taken over five centuries. It includes, but is not limited to, the processes and practices of resistance, refusal, and dismantling of the political, economic, social, and spiritual structures constructed by colonizers.[75]

Mauna Kea

Since the first 12.5-inch telescope and state-funded six-mile road were built in 1964, Mauna Kea has become a world-class astronomical observatory hosting some of the largest instruments of science in the world. It has also become a site of conflict between Kanaka ‘Oiwi and people who want more telescopes. The battle over development on Mauna a Wakea is like the broader struggle over Hawai’i. Indeed, the protests against astronomy expansion on Mauna a Wakea are a symptom of 125 years of military occupation of Hawai’I by the United States. Hawaiians have, for just as long, fought against a settler state dependent on the excesses of tourism and a distortion of history. Today, Western astronomy’s cultural imperative to explore the universe and discover new worlds provides new justification for further land grabs. As an advocate for the protection of our ancestral homelands and our people’s future, I write about Mauna a Wakea as a symbol of our collective struggle for life, land, and independence to contribute to raising a critical consciousness about settler colonization under U.S occupation....[76]

Georgia O’Keeffe

"In 1939 Georgia O’Keeffe traveled to the Territory of Hawai‘i to fulfill a commission for the advertising agency N. W. Ayer & Son. Her expenses were covered in exchange for two paintings to be used in advertisements for the Hawaiian Pineapple Company (now Dole Food Company), an enterprise entangled with the conquest of Hawai‘i. James Dole built his pineapple empire on the dispossession and oppression of Indigenous Hawaiians by U.S. missionaries, businessmen, and politicians. O’Keeffe’s experiences in and paintings of Hawai‘i were structured by colonialism, and Dole advertisements that feature her paintings served to justify and naturalize U.S. conquest. To understand O’Keeffe’s work as participating in the highly racialized project of colonialism is to disrupt dominant histories that, often unwittingly, contribute to the ongoing disenfranchisement of Indigenous peoples. Doing so is an important step toward “decolonizing” the history of American modernism."[77]

Cited

- ↑ https://www.iwgia.org/en/usa/4222-iw-2021-hawai-i.html

- ↑ https://www.hawaiinewsnow.com/2023/08/11/maui-reports-12-additional-wildfire-fatalities-bringing-death-toll-67/

- ↑ https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2023/08/11/maui-hawaii-fire-live-updates/70573053007/

- ↑ https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/2023/08/12/maui-fire-hawaii-wildfire-death-toll-lahaina/

- ↑ https://www.mauicounty.gov/CivicAlerts.aspx?AID=12682

- ↑ https://people.com/estimated-1000-people-missing-in-hawaii-amid-wildfires-7642760

- ↑ https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/live-blog/maui-fires-live-updates-hawaii-death-toll-missing-search-rescue-rcna99570

- ↑ https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/live-blog/maui-fires-live-updates-lahaina-rcna99396

- ↑ https://www.emdat.be/

- ↑ https://www.reuters.com/world/us/maui-inferno-what-are-deadliest-wildfires-us-history-2023-08-13/

- ↑ https://earthjustice.org/feature/background-on-na-wai-eha

- ↑ https://earthjustice.org/feature/background-on-na-wai-eha

- ↑ https://www.democracynow.org/2023/8/11/maui_fires

- ↑ https://www.democracynow.org/2023/8/11/maui_fires

- ↑ https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2023/aug/11/hawaii-fires-made-more-dangerous-by-climate-crisis

- ↑ https://www.nbcnews.com/science/science-news/drought-wind-mauis-wildfires-turned-historic-tragedy-rcna99196

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Ellsworth, L. M., Litton, C. M., Dale, A. P., & Miura, T. (2014). Invasive grasses change landscape structure and fire behaviour in Hawaii. Applied Vegetation Science, 17(4), 680–689. doi:10.1111/avsc.12110

- ↑ https://www.democracynow.org/2023/8/11/hawaii_maui_clay_trauernicht_tropical_fires

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 https://apnews.com/article/hawaii-wildfires-climate-change-92c0930be7c28ec9ac71392a83c87582

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 https://www.forbes.com/sites/brianbushard/2023/08/10/whats-causing-hawaiis-deadly-wildfires-experts-point-to-flammable-grasses-drought-and-hurricane-winds/?sh=344f191a3dcb

- ↑ Nugent, A. D., R. J. Longman, C. Trauernicht, M. P. Lucas, H. F. Diaz, and T. W. Giambelluca, 2020: Fire and Rain: The Legacy of Hurricane Lane in Hawaiʻi. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc., 101, E954–E967, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-19-0104.1.

- ↑ https://www.nbcnews.com/science/science-news/drought-wind-mauis-wildfires-turned-historic-tragedy-rcna99196

- ↑ https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-08-11/why-have-the-maui-hawaii-wildfires-been-so-deadly/102718688

- ↑ https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/hawaiians-strike-against-sugar-industry-hawaii-hawaii-1946

- ↑ Stephanie Nohelani Teves, 2019. "Princess Kaʻiulani Haunts Empire in Waikīkī", Detours: A Decolonial Guide to Hawai'i, Hokulani K. Aikau, Vernadette Vicuna Gonzalez

- ↑ AIKAU, H. K., & GONZALEZ, V. V. (Eds.). (2019). Detours: A Decolonial Guide to Hawai’i. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv11smvvj; Page, 89

- ↑ https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/kahoolawe-island-us-navy

- ↑ https://www.hawaiinewsnow.com/story/37604472/the-bombing-of-kahoolawe-went-on-for-decades-clean-up-will-take-generations/

- ↑ https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/kahoolawe-island-us-navy

- ↑ https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/kahoolawe-island-us-navy

- ↑ https://www.dtra.mil/Portals/61/Documents/History/Defense%27s%20Nuclear%20Agency%201947-1997.pdf

- ↑ https://www.hawaiinewsnow.com/story/37604472/the-bombing-of-kahoolawe-went-on-for-decades-clean-up-will-take-generations/

- ↑ https://www.hawaiinewsnow.com/story/37604472/the-bombing-of-kahoolawe-went-on-for-decades-clean-up-will-take-generations/

- ↑ https://www.hawaiipublicradio.org/local-news/navy-red-hill-fuel-timeline

- ↑ https://www.staradvertiser.com/2014/06/22/breaking-news/more-tiny-holes-found-in-leaking-red-hill-fuel-storage-tank/

- ↑ https://www.civilbeat.org/beat/navy-stops-red-hill-pipeline-leak-of-fuel-and-water-that-began-saturday/

- ↑ https://www.hawaiinewsnow.com/2021/12/01/live-doh-discusses-latest-investigation-into-possible-tainted-water/

- ↑ https://www.epa.gov/red-hill/about-red-hill-fuel-releases

- ↑ https://www.civilbeat.org/2022/11/hundreds-of-red-hill-families-still-sick-a-year-later-survey-finds/

- ↑ https://www.civilbeat.org/2022/11/hundreds-of-red-hill-families-still-sick-a-year-later-survey-finds/

- ↑ https://guides.westoahu.hawaii.edu/alohaaina/redhillfueltanks

- ↑ https://www.hawaiinewsnow.com/2022/03/09/pentagon-concedes-red-hill-tanks-pose-imminent-threat-aquifer/

- ↑ https://www.hawaiinewsnow.com/2022/12/13/bws-says-navy-detected-pfas-forever-chemicals-drinking-water-pearl-harbor-base-last-year-2020/

- ↑ https://www.hawaiinewsnow.com/2022/12/10/epa-doh-letter-reveals-pfas-forever-chemicals-detected-groundwater-near-red-hill-last-december/

- ↑ https://www.epa.gov/red-hill/fire-suppressant-afff-spill

- ↑ https://www.civilbeat.org/2022/11/a-new-leak-at-red-hill-dumps-hundreds-of-gallons-of-firefighting-foam/

- ↑ https://www.poisoningparadise.com/

- ↑ https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/items/a5c57862-07b7-4dbc-ac97-8faaf15f5aaa

- ↑ https://www.syngenta.com/en/company/our-purpose-and-contribution

- ↑ https://beyondpesticides.org/dailynewsblog/2014/05/report-finds-pesticide-residues-in-hawaiis-waterways/

- ↑ https://grist.org/business-technology/gmo-companies-are-dousing-hawaiian-island-with-toxic-pesticides/

- ↑ https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2018-02/documents/fifra-09-2017-0001-syngenta_seeds_llc_amended_complaint-2018-01-12.pdf

- ↑ https://www.epa.gov/archive/epa/newsreleases/epa-reaches-agreement-syngenta-farmworker-safety-violations-kauai.html

- ↑ https://www.civilbeat.org/2018/02/epa-settles-syngenta-pesticide-claim-for-pennies-on-the-dollar/

- ↑ https://www.epa.gov/archive/epa/newsreleases/epa-reaches-agreement-syngenta-farmworker-safety-violations-kauai.html

- ↑ https://www.civilbeat.org/2018/02/epa-settles-syngenta-pesticide-claim-for-pennies-on-the-dollar/

- ↑ https://www.seedtoday.com/article/121164/hartung-brothers-inc-completes-acquisition-of-syngenta-operations-in-hawaii

- ↑ https://www.hortidaily.com/article/6034766/us-hartung-brothers-to-acquire-syngenta-operations-in-hawaii/

- ↑ https://hartungbrothers.com/source-from-us/

- ↑ https://www.earthisland.org/journal/index.php/magazine/entry/toxic-drift/

- ↑ https://www.earthisland.org/journal/index.php/articles/entry/monsanto-guilty-of-spraying-banned-pesticide-on-maui-fields/

- ↑ https://www.earthisland.org/journal/index.php/articles/entry/monsanto-guilty-of-spraying-banned-pesticide-on-maui-fields/

- ↑ https://apnews.com/article/business-environment-and-nature-crime-hawaii-honolulu-ed13f915250b1e1fbb4ffb7ed2e5ab71

- ↑ https://www.poisoningparadise.com/

- ↑ Casumbal-Salazar, Iokepa. "“Where Are Your Sacred Temples?” Notes on the Struggle for Mauna a Wākea". Detours: A Decolonial Guide to Hawai'i, edited by Hokulani K. Aikau and Vernadette Vicuña Gonzalez, New York, USA: Duke University Press, 2019, pp. 200-210. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781478007203-025

- ↑ Casumbal-Salazar, Iokepa. "“Where Are Your Sacred Temples?” Notes on the Struggle for Mauna a Wākea". Detours: A Decolonial Guide to Hawai'i, edited by Hokulani K. Aikau and Vernadette Vicuña Gonzalez, New York, USA: Duke University Press, 2019, pp. 200-210. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781478007203-025

- ↑ Casumbal-Salazar, Iokepa. "“Where Are Your Sacred Temples?” Notes on the Struggle for Mauna a Wākea". Detours: A Decolonial Guide to Hawai'i, edited by Hokulani K. Aikau and Vernadette Vicuña Gonzalez, New York, USA: Duke University Press, 2019, pp. 200-210. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781478007203-025

- ↑ https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/govbeat/wp/2013/09/27/hawaiis-14-billion-tourism-industry-back-to-pre-recession-levels/?noredirect=on

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tourism_in_Hawaii#cite_note-RR-17-1

- ↑ https://www.dukeupress.edu/detours

- ↑ AIKAU, H. K., & GONZALEZ, V. V. (Eds.). (2019). Detours: A Decolonial Guide to Hawai’i. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv11smvvj

- ↑ https://www.kcrw.com/news/shows/press-play-with-madeleine-brand/hawaii-island-sex-drinks-insurrection/larry-ellison-lanai

- ↑ AIKAU, H. K., & GONZALEZ, V. V. (Eds.). (2019). Detours: A Decolonial Guide to Hawai’i. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv11smvvj; Page, 87

- ↑ AIKAU, H. K., & GONZALEZ, V. V. (Eds.). (2019). Detours: A Decolonial Guide to Hawai’i. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv11smvvj; Page, 87

- ↑ AIKAU, H. K., & GONZALEZ, V. V. (Eds.). (2019). Detours: A Decolonial Guide to Hawai’i. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv11smvvj

- ↑ Casumbal-Salazar, Iokepa. "“Where Are Your Sacred Temples?” Notes on the Struggle for Mauna a Wākea". Detours: A Decolonial Guide to Hawai'i, edited by Hokulani K. Aikau and Vernadette Vicuña Gonzalez, New York, USA: Duke University Press, 2019, pp. 200-210. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781478007203-025

- ↑ https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/710471