Indigenous Food Sovereignty

Before colonization Indigenous Nations across Turtle Island were thriving civilizations[1] with complex societies and differing customs.[2][3][4]

In fact without the aid of The Wampanoag Nation and their established Food Sovereignty some of the first settlers would not have been able to survive the winters and would have either starved or froze to death. The Wampanoag had a deep relationship with the land and the creatures they shared it with:

“We have lived with this land for thousands of generations—fishing in the waters, planting and harvesting crops, hunting the four-legged and winged beings and giving respect and thanks for each and every thing taken for our use. We were originally taught to use many resources, remembering to use them with care, respect, and with a mind towards preserving some for the seven generations of unborn, and not to waste anything.”[5]

There were many types of agriculture, means to sustenance and land management techniques across the so called Americas.[6][7] A common myth is that Indigenous Nations were barely surviving before European colonization, but this is not accurate:

... “everyone would help themselves, eat when you are hungry, [there was] always food for everyone, and the fires never went out, the coals were always kept going… food was communal with a preference for the youth and elderly to eat first.” ...

“we need to get rid of this idea that we were barely getting by and starving. We had vast food reserves and never went hungry – there was much abundance.”[8]

Indigenous techniques of agriculture are typically rooted in a deep sense of place and understanding of the local environment- These techniques/considerations offer much guidance and a framework to transition away from the industrial agricultural system dominating the Earth today.[9] Before European colonization many Indigenous Nations were already practicing sustainable regenerative agriculture, which have influenced many sustainable agriculture techniques in the status quo (agroecology/permaculture.) [10] The reality of advanced agriculture techniques flies in the face of the myth of settlers reaching a pristine untouched land; Indigenous Nations had been stewards over Turtle Island since time immemorial.

Indigenous Nations practiced regenerative agriculture in part to ensure that soils would be capable of continued food production for the future Seven Generations, but also because of a sense of responsibility/stewardship for the environment, which is in stark contrast of European conceptions of the world which revolve around domination and 'taming of the wild.'

Forced Food Insecurity

Government policies encouraging settler colonialism in addition to land theft/ not honoring treaties decimated traditional food pathways Indigenous Nations had forged for millennia before the arrival of European settlers.[11] Continued land theft and forced removal from their homelands onto foreign reservations further deepened Indigenous Nation's food insecurity and dependence upon food from the United States government (food described as not fit for soldiers by the United States.)

The United States Federal Government provides food rations to many Nations, because of previous agreements/ treaties. The food rations are typically unhealthy and have no relationship with traditional foods: "Diabetes was rare among Native peoples before the 1940s (the Navajo language had no word for diabetes prior to European arrival, for example) but exploded in the wake of commodity distribution, strongly contributing to the obesity and diabetes epidemics that Native communities are currently fighting."[12]

1887 Dawes Act

Food insecurity among Tribal communities today cannot be divorced from their land history, as federal policy promoted settler-colonialism and land theft, which disrupted Tribal communities’ food systems. One pivotal law is the 1887 Dawes Act, under which the U.S. government appropriated — effectively stole — collectively held Native land and then parceled it back to individual Native people (“allottees”). Typically 40, 80, or 160 acres in area, these parcels were held in trust by the federal government on behalf of allotees for 25 years, during which they were not subject to taxation. Allotees could manage the land but could not lease or sell it without government consent. Under the Dawes Act, after 25 years elapsed, allotees would own the land “fee simple,” meaning they would have full ownership and the ability to develop and manage the land as they wished. The land would also become subject to taxation at this time.

This policy was conceived of as a “civilizing” boon to Indian Country. Native peoples would engage in land ownership patterns like white Americans. They would enter the mainstream economy and become “self-sufficient,” by Euro-American standards. They would shift from traditional agricultural practices, adopting Euro-American planting methods and cultivating cash crops for sale. By assimilating into the dominant culture, proponents of the policy argued, Native peoples could secure their futures.[13]

Subsequent government policies continued to chip away at native lands- From the 1880s to 1934, allotment policy transferred 90 million acres of land from Native to non-Native ownership- the size of Montana. Through these policies food sovereignty for Native Nations is near impossible, because much Native land is controlled by the United States Federal Government and usage of the land must be approved by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA.) This has resulted in dependency upon government rations and is a continuation of the same genocidal tactics used in the past by the United States government.

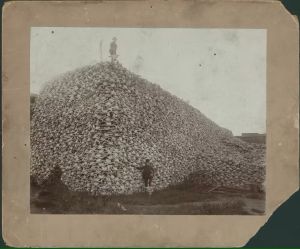

Buffalo Genocide

The Oceti Sakowin had a profound relationship with the Buffalo, so much so they considered themselves to be the Pte Oyate (Buffalo Nation:)

It all started in the 19th century when herds of 4 million American bison lived in the Great Plains and provided significant resources for the people that thrived there – such as food, medicine, clothing, shelter, tools, utensils, decoration and playthings. The buffalo was so valuable that the people of the Great Sioux called themselves Pte Oyate (Buffalo Nation) and stories of creation emerged detailing the buffalo using its nose to create a human from a pile of mud.[14]

North American Buffalo populations are estimated to have been in the 30-50 millions before European contact.[15] Generals William T. Sherman and Philip Sheridan spearheaded the military tactic of en masse slaughter of the buffalo in an attempt to "civilize" Indigenous Nations across the plains: "On 26 June 1869, the prestigious Army-Navy Journal reported that 'General Sherman remarked, in conversation the other day, that the quickest way to compel the Indians to settle down to civilized life was to send ten regiments of soldiers to the plains, with orders to shoot buffaloes until they became too scarce to support the redskins.'"[16]

Soon, it became the norm for Sherman and Sheridan to provide opportunities for the rich and influential to travel West and hunt Buffalo with U.S. Cavalry guns alongside prominent generals like General William F. Cody (Buffalo Bill Cody), who claimed to kill 4,000 Buffalo himself. "In fact, the Springfield army rifle was initially the favorite weapon of the hide hunters. The party killed over six hundred Buffalo on the hunt, keeping only the tongues and the choice cuts, but leaving the rest of the carcasses to rot on the plains."[17]

In a fifty-five-year period, 1830-1885, soldiers, hunters, and settlers killed more than 40 million Buffalo.

For millennia to follow, the tribes moved wherever the buffalo migrated. People among the tribes were well fed and no one ever got sick. That was until the Europeans colonized the Lakota territory and destroyed the culture that surrounded the buffalo. The mercenaries slaughtered millions of buffalo and the self-sufficient nature of the tribes ceased .After several years, the people were introduced to processed and canned carbohydrates, fats, salts, sugars, and preservatives. “Our warriorhood was lost when we accepted the food”. And, not only was the warriorhood lost, but public health issues began to arise such as heart disease, high blood pressure, obesity – and they still remain today.[18]

The genocide of the Buffalo completely ruptured the means to sustenance of the Oceti Sakowin, and altered their way of life permanently. The decimation of the buffalo is only but one example of the ways the United States government plotted and executed plans to disrupt Indigenous Nations sustainable symbiotic relationship with the land and all creatures they shared it with.[19]

Sources

- ↑ https://fncaringsociety.com/sites/default/files/Indigenous%20Contributions%20to%20North%20America%20and%20the%20World.pdf

- ↑ Clement, R. M., & Horn, S. P. (2001). Pre-Columbian land-use history in Costa Rica: a 3000-year record of forest clearance, agriculture and fires from Laguna Zoncho. The Holocene, 11(4), 419–426.

- ↑ Graeber, D., & Wengrow, D. (2021). The dawn of everything: a new history of humanity. First American edition. New York, Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- ↑ Keeler, K. (2022). Before colonization (BC) and after decolonization (AD): The Early Anthropocene, the Biblical Fall, and relational pasts, presents, and futures. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, 5(3), 1341–1360. https://doi.org/10.1177/25148486211033087

- ↑ https://www.nlm.nih.gov/nativevoices/timeline/200.html

- ↑ https://nfu.org/2020/10/12/the-indigenous-origins-of-regenerative-agriculture/

- ↑ https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/the-historical-determinants-of-food-insecurity-in-native-communities

- ↑ https://branchoutnow.org/growing-sovereignty-turtle-island-and-the-future-of-food/#comments

- ↑ Bethany Elliott, Deepthi Jayatilaka, Contessa Brown, Leslie Varley, Kitty K. Corbett, "“We Are Not Being Heard”: Aboriginal Perspectives on Traditional Foods Access and Food Security", Journal of Environmental and Public Health, vol. 2012, Article ID 130945, 9 pages, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/130945

- ↑ https://nfu.org/2020/10/12/the-indigenous-origins-of-regenerative-agriculture/

- ↑ https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/the-historical-determinants-of-food-insecurity-in-native-communities

- ↑ https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/the-historical-determinants-of-food-insecurity-in-native-communities

- ↑ https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/the-historical-determinants-of-food-insecurity-in-native-communities

- ↑ https://www.cwis.org/2020/07/buffalo-are-the-backbone-of-lakota-food-sovereignty/

- ↑ Dunbar-Ortiz, R. (2015). An indigenous peoples' history of the United States. Boston, Beacon Press.

- ↑ https://blog.nativehope.org/how-the-destruction-of-the-buffalo-impacted-native-americans

- ↑ https://blog.nativehope.org/how-the-destruction-of-the-buffalo-impacted-native-americans

- ↑ https://www.cwis.org/2020/07/buffalo-are-the-backbone-of-lakota-food-sovereignty/

- ↑ https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2016/05/the-buffalo-killers/482349/