Pte Oyate

Regenerative Grazing

More than five thousand years ago, Indigenous nations of the Great Plains of Turtle Island observed that the fires started by lightning spurred new growth of fresh green grass.[1]

As buffalo love to feast on the nutritious shoots which sprout from recently burned areas, these fires would draw massive herds of bison from hundreds, even thousands of miles away.[2] The importance of these fires for buffalo hunters earned them the name, the Red Buffalo. By mimicking these natural fires through controlled burning, the Tribes cultivated grasslands of fresh green growth to attract buffalo herds and reduce the need for extensive tracking and hunting.

Through this grasslands stewardship, Native peoples "amplified the climate signal in prairie fire patterns" correlated with wet seasons by making the most of rain-fed growth to fuel new fires.[3] This improved the biodiversity of prairie grasslands by creating greater between-patch diversity, which is especially important for small animals.[4]

As grasses burned to cultivate new growth, the Tribes also gradually built up layers of rich charcoal residue in prairie soils with all the benefits that follow. A research collaboration between the Blackfeet Tribal Historic Preservation Office and Southern Methodist University produced unequivocal evidence of these historic practices, as "all of the charcoal layers that were dated perfectly aligned with the time that Natives used drivelines."[5] [6] The results of their study showed the historical depth and indigenuity of traditional bison-hunting and controlled burning practices, with the generation of biochar serving as a lasting signature in the soil indicating when and where these practices were adopted.

Tȟatȟáŋka Genocide

See: Red Meat Republic; Oceti Sakowin; Indigenous Food Sovereignty; Traditional Ecological Knowledge

It all started in the 19th century when herds of 4 million American bison lived in the Great Plains and provided significant resources for the people that thrived there – such as food, medicine, clothing, shelter, tools, utensils, decoration and playthings. The buffalo was so valuable that the people of the Great Sioux called themselves Pte Oyate (Buffalo Nation) and stories of creation emerged detailing the buffalo using its nose to create a human from a pile of mud.[7]

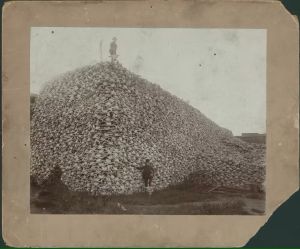

North American Buffalo populations are estimated to have been in the 30-50 millions before European contact.[8] Generals William T. Sherman and Philip Sheridan spearheaded the military tactic of en masse slaughter of the buffalo in an attempt to "civilize" Indigenous Nations across the plains: "On 26 June 1869, the prestigious Army-Navy Journal reported that 'General Sherman remarked, in conversation the other day, that the quickest way to compel the Indians to settle down to civilized life was to send ten regiments of soldiers to the plains, with orders to shoot buffaloes until they became too scarce to support the redskins.'"[9]

Soon, it became the norm for Sherman and Sheridan to provide opportunities for the rich and influential to travel West and hunt Buffalo with U.S. Cavalry guns alongside prominent generals like General William F. Cody (Buffalo Bill Cody), who claimed to kill 4,000 Buffalo himself. "In fact, the Springfield army rifle was initially the favorite weapon of the hide hunters. The party killed over six hundred Buffalo on the hunt, keeping only the tongues and the choice cuts, but leaving the rest of the carcasses to rot on the plains."[10]

In a fifty-five-year period, 1830-1885, soldiers, hunters, and settlers killed more than 40 million Buffalo.

For millennia to follow, the tribes moved wherever the buffalo migrated. People among the tribes were well fed and no one ever got sick. That was until the Europeans colonized the Lakota territory and destroyed the culture that surrounded the buffalo. The mercenaries slaughtered millions of buffalo and the self-sufficient nature of the tribes ceased .After several years, the people were introduced to processed and canned carbohydrates, fats, salts, sugars, and preservatives. “Our warriorhood was lost when we accepted the food”. And, not only was the warriorhood lost, but public health issues began to arise such as heart disease, high blood pressure, obesity – and they still remain today.[11]

The genocide of the Buffalo completely ruptured the means to sustenance of the Oceti Sakowin, and altered their way of life permanently. The decimation of the buffalo is only but one example of the ways the United States government plotted and executed plans to disrupt Indigenous Nations sustainable symbiotic relationship with the land and all creatures they shared it with.

Sources

- ↑ https://www.nps.gov/tapr/learn/nature/fire-regime.htm

- ↑ http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2018/07/17/1805259115

- ↑ https://news.arizona.edu/story/native-bison-hunters-amplified-climate-impacts-prairie-fires

- ↑ https://arstechnica.com/science/2018/07/native-americans-managed-the-prairie-for-better-bison-hunts/

- ↑ https://www.futurity.org/native-americans-fire-bison-hunts/

- ↑ https://wildlife.org/native-americans-used-fire-to-hunt-bison/

- ↑ https://www.cwis.org/2020/07/buffalo-are-the-backbone-of-lakota-food-sovereignty/

- ↑ Dunbar-Ortiz, R. (2015). An indigenous peoples' history of the United States. Boston, Beacon Press.

- ↑ https://blog.nativehope.org/how-the-destruction-of-the-buffalo-impacted-native-americans

- ↑ https://blog.nativehope.org/how-the-destruction-of-the-buffalo-impacted-native-americans

- ↑ https://www.cwis.org/2020/07/buffalo-are-the-backbone-of-lakota-food-sovereignty/