Traditional Ecological Knowledge

Summary

Traditional Ecological Knowledge has been employed by Indigenous Nations since time immemorial and provides a framework necessary to transition away from capitalism and industrial agriculture towards true Food Sovereignty. Winona LaDuke explains this concept:

"Minobimaatisiiwin," or the "good life," is the basic objective of the Anishinabeg and Cree people who have historically, and to this day, occupied a great portion of the north-central region of the North American continent. An alternative interpretation of the word is "continuous rebirth." This is how we traditionally understand the world and how indigenous societies have come to live within natural law. Two tenets are essential to this paradigm: cyclical thinking and reciprocal relations and responsibilities to the Earth and creation. Cyclical thinking, common to most indigenous or land-based cultures and value systems, is an understanding that the world (time, and all parts of the natural order-including the moon, the tides, women, lives, seasons, or age) flows in cycles. Within this understanding is a clear sense of birth and rebirth and a knowledge that what one does today will affect one in the future, on the return. A second concept, reciprocal relations, defines responsibilities and ways of relating between humans and the ecosystem. Simply stated, the resources of the economic system, whether they be wild rice or deer, are recognized as animate and, as such, gifts from the Creator. Within that context, one could not take life without a reciprocal offering, usually tobacco or some other recognition of the Anishinabeg's reliance on the Creator. There must always be this reciprocity. Additionally, assumed in the "code of ethics" is an understanding that "you take only what you need, and you leave the rest."[1]

Intellectual Colonization

See also: Knowledge commons

The disappearance of local knowledge through its interaction with the dominant western knowledge takes place at many levels, through many steps. First, local knowledge is made to disappear by simply not seeing it, by negating its very existence. This is very easy in the distant gaze of the globalizing dominant system. The western systems of knowledge have generally been viewed as universal. However, the dominant system is also a local system, with its social basis in a particular culture, class and gender. It is not universal in an epistemological sense. It is merely the globalized version of a very local and parochial tradition. Emerging from a dominating and colonizing culture, modern knowledge systems are themselves colonizing.[2]

... The first level of violence unleashed on local systems of knowledge is to not see them as knowledge. This invisibility is the first reason why local systems collapse without trial and test when confronted with the knowledge of the dominant west. The distance itself removes local systems from perception. When local knowledge does appear in the field of the globalizing vision, it is made to disappear by denying it the status of a systematic knowledge, and assigning it the adjectives 'primitive' and 'unscientific'. Correspondingly, the western system is assumed to be uniquely 'scientific' and universal. The prefix 'scientific' for the modern systems, and 'unscientific' for the traditional knowledge systems has, however, less to do with knowledge and more to do with power. The models of modern science which have encouraged these perceptions were derived less from familiarity with actual scientific practice, and more from familiarity with idealized versions of which gave science a special epistemological status. Positivism, verificationism, falsificationism were all based on the assumption that unlike traditional, local beliefs of the world, which are socially constructed, modern scientific knowledge was thought to be determined without social mediation. Scientists, in accordance with an abstract scientific method, were viewed as putting forward statements corresponding to the realities of a directly observable world. The theoretical concepts in their discourse were in principle seen as reducible to directly verifiable observational claims. New trends in the philosophy and sociology of science challenged the positivist assumptions, but did not challenge the assumed superiority of western systems. Thus, Kuhn, who has shown that science is not nearly as open as is popularly thought, and is the result of the commitment of a specialist community of scientists to presupposed metaphors and paradigms which determine the meaning of constituent terms and concepts, still holds that modern 'paradigmatic' knowledge, is superior to pre-paradigmatic knowledge which represents a kind of primitive state of knowing.[3]

Land

Native peoples throughout the Western Hemisphere have their own creation narratives about their origins, how their ancestors came to the land as place, and how places are imbued with relationships between other than human beings and beings that became human. The original stories of how Native people came to the land are told through emergence from lower worlds into new worlds or through relationships between humans and holy beings from the Sky and the Earth. Today, this knowledge of our origins, of how to live properly, lies within our respective epistemologies and continues to be conveyed not only through ceremonies and prayer but also through acts of resistance to ongoing Native dispossession.

Since their first appearances in what they called the "New World," waves of European settlers, and then Americans, have been devoted to wresting land and its resources from Native peoples to sustain settler life. Patrick Wolfe argues that "Land is life-- or, at least, land is necessary for life. Thus, contests for land can be --indeed, often are-- contests for life." Targeted for elimination because of their status as the original peoples who lived on and with the land, Native people were eliminated as "Indians," while enslaved Africans were targeted for elimination for their labor. As Deborah Bird Rose points out, all Native people had to do to be in the way of settler colonization was to stay home.

The shift in the way land is conceived of, even by Native peoples, is through capitalism, which regards land as property. Capitalism organized around the private ownership of the means of production (land, resources, capital) and the private control of the wealth produced by wage laborers became the means through which Native peoples were dispossessed of approximately 97 percent of land in the current United States. By the late nineteenth century and into the early twentieth century, Native people had been removed onto small tracts of land deemed wastelands by settlers. The 97 percent of remaining lands outside of these "reservations" were developed into bordertowns, which carried with them all the legal, social, and spatial fictions that made these lands alien and hostile to Indians who happened to wander "off the reservation."[4]

Indigenous Food Sovereignty

Legacies of Indigenous Food Sovereignty offer many pathways to achieve food sovereignty for everyone on earth in a sustainable manner taking into account local environments and the affects of food production on said environments.[5]

Before colonization Indigenous Nations across Turtle Island were thriving civilizations[6] with complex societies and differing customs.[7][8][9]

In fact without the aid of The Wampanoag Nation some of the first settlers would not have been able to survive the winters and would have either starved or froze to death. The Wampanoag had a deep relationship with the land and the creatures they shared it with:

“We have lived with this land for thousands of generations—fishing in the waters, planting and harvesting crops, hunting the four-legged and winged beings and giving respect and thanks for each and every thing taken for our use. We were originally taught to use many resources, remembering to use them with care, respect, and with a mind towards preserving some for the seven generations of unborn, and not to waste anything.”[10]

There were many types of agriculture, means to sustenance and land management techniques across the so called Americas.[11][12] A common myth is that Indigenous Nations were barely surviving before European colonization and that Indigenous Nations lived within an untouched undisturbed landscape [13], but this is not accurate:

... “everyone would help themselves, eat when you are hungry, [there was] always food for everyone, and the fires never went out, the coals were always kept going… food was communal with a preference for the youth and elderly to eat first.” ...

“we need to get rid of this idea that we were barely getting by and starving. We had vast food reserves and never went hungry – there was much abundance.”[14]

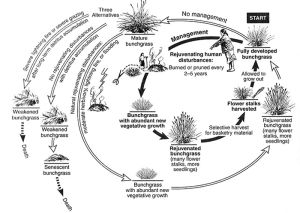

Indigenous techniques of agriculture are typically rooted in a deep sense of place and understanding of the local environment- These techniques/considerations offer much guidance and a framework to transition away from the industrial agricultural system dominating the Earth today (Traditional Ecological Knowledge.)[15] Before European colonization many Indigenous Nations were already practicing sustainable regenerative agriculture, which have influenced many sustainable agriculture techniques in the status quo (agroecology/permaculture.) [16] The reality of advanced agriculture techniques flies in the face of the myth of settlers reaching a pristine untouched land; Indigenous Nations had been stewards over Turtle Island since time immemorial.

Indigenous Nations practiced regenerative agriculture in part to ensure that soils would be capable of continued food production for the future Seven Generations, but also because of a sense of responsibility/stewardship for the environment, which is in stark contrast of European conceptions of the world which revolve around domination and 'taming of the wild.'

Klinic Garden

The Klinic Garden is a permaculture 'U-Pick' community garden in Winnipeg, Manitoba in so called Canada, which utilizes Traditional Ecological Knowledge. The garden is led by Audrey Logan (many people call her ‘Auntie,') and she emphasizes a return to Indigenous place based gardening. The garden is open to the general public to pick any food or medicine freely; Auntie holds group gardening days typically once a week during the growing season, which allows the general public to learn about Indigenous permaculture while contributing to the garden- in this way the garden also serves as a knowledge commons.

Her teachings emphasize that many plants the general public consider weeds have medicinal value (for example thistle is good for liver cleansing, but is often considered a weed.)

Blood Knowledge

"Blood Knowledge" is another concept Auntie discusses through her teachings; Blood Knowledge is knowledge passed down to children through their mothers in the womb. Auntie emphasizes that everyone has knowledge about the Earth, plants, and ecology, but it has to be tapped into through experience.

Blood knowledge is a path towards true food sovereignty through the recognition that we are all potential stewards of the earth and can all contribute to the production of local healthy food. Auntie explains the concept of blood knowledge in her zine:

I want to make sure to claim the knowledge of what I learned on my own as being my own knowledge— to say that I didn’t have to live with her in the bush, to know all this stuff that’s already in my blood. So blood knowledge, as we now know, the DNA of our grandmothers are in us when our mothers carry us, and everyone has it, it’s in our DNA. So to acknowledge that instead of— she shared with me some stories, and I gathered some too, by following the old trade route trails unknowingly.

We have a lot of young kids, they have it in their genes, their blood, but if they don’t acknowledge it and if they think that they can’t get it because they haven’t gotten it through their ancestors that they could never meet because of a system of separation— that would be wrong. But they can actually hear their ancestors who are there with them, their voices— if they learn to listen. There are times when auntie speaks, when I hear her, and i’m like ‘whoah!’ And when I was younger that was called crazy. But now we know it’s not craziness, it’s connection.[17]

The Lesson of the Squirrel

In the time of the great learning when the plants and animals were teaching the humans how to live with nature, each had a gift to give them: the great Bear taught about medicines and even the Squirrel had a lesson to teach them. This is that lesson.

Since during the snow time, fresh foods were not to be found, even when the humans traveled to warm places, but when the ice came they needed to store foods that were easy to carry and would not go bad. The squirrel showed the way to dry the foods by making it into smaller pieces and drying the pieces in the sun up on branches. The humans saw how the items dried and would not go bad, up in the branches where the wind blew and the sun cleaned the goods well.

These items can still be found along branches today as squirrel still dries their goods to store for winter in their nests. Following these teachings the peoples were able to preserve their foods for trade and turned into many foods and flours for winter use. Water ceremony was done when rehydrating the foods, as water returned life to the dried goods so many could be fed.

These goods can still be found in caches across Turtle Island in bogs and in-ground graineries as well buried well into the earth as pemmican. These tools for storage and food preservation can be revitalized for future food security using old knowledge with new tools. - Audrey Logan[18]

Sources

- ↑ http://www.uky.edu/~rsand1/china2017/library/NOTES/LaDuke%20-%20Traditional%20Ecological%20Knowledge%20-%20Notes.pdf

- ↑ Shiva, V. (1993). Monocultures of the Mind—Understanding the Threats to Biological and Cultural Diversity. Indian Journal of Public Administration, 39(3), 237–248. https://doi.org/10.1177/0019556119930304

- ↑ Shiva, V. (1993). Monocultures of the Mind—Understanding the Threats to Biological and Cultural Diversity. Indian Journal of Public Administration, 39(3), 237–248. https://doi.org/10.1177/0019556119930304

- ↑ Estes, N., Benallie, B., Denetdale, J., Cody, R., Correia, D., & Yazzie, M. K. (2021). Red nation rising: From bordertown violence to native liberation; Page 120-121

- ↑ Bethany Elliott, Deepthi Jayatilaka, Contessa Brown, Leslie Varley, Kitty K. Corbett, "“We Are Not Being Heard”: Aboriginal Perspectives on Traditional Foods Access and Food Security", Journal of Environmental and Public Health, vol. 2012, Article ID 130945, 9 pages, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/130945

- ↑ https://fncaringsociety.com/sites/default/files/Indigenous%20Contributions%20to%20North%20America%20and%20the%20World.pdf

- ↑ Clement, R. M., & Horn, S. P. (2001). Pre-Columbian land-use history in Costa Rica: a 3000-year record of forest clearance, agriculture and fires from Laguna Zoncho. The Holocene, 11(4), 419–426.

- ↑ Graeber, D., & Wengrow, D. (2021). The dawn of everything: a new history of humanity. First American edition. New York, Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- ↑ Keeler, K. (2022). Before colonization (BC) and after decolonization (AD): The Early Anthropocene, the Biblical Fall, and relational pasts, presents, and futures. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, 5(3), 1341–1360. https://doi.org/10.1177/25148486211033087

- ↑ https://www.nlm.nih.gov/nativevoices/timeline/200.html

- ↑ https://nfu.org/2020/10/12/the-indigenous-origins-of-regenerative-agriculture/

- ↑ https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/the-historical-determinants-of-food-insecurity-in-native-communities

- ↑ https://jan.ucc.nau.edu/~alcoze/for398/class/pristinemyth.html

- ↑ https://branchoutnow.org/growing-sovereignty-turtle-island-and-the-future-of-food/#comments

- ↑ Bethany Elliott, Deepthi Jayatilaka, Contessa Brown, Leslie Varley, Kitty K. Corbett, "“We Are Not Being Heard”: Aboriginal Perspectives on Traditional Foods Access and Food Security", Journal of Environmental and Public Health, vol. 2012, Article ID 130945, 9 pages, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/130945

- ↑ https://nfu.org/2020/10/12/the-indigenous-origins-of-regenerative-agriculture/

- ↑ http://www.nmfccc.ca/uploads/4/4/1/7/44170639/dehydration_nations_zine.pdf

- ↑ http://www.nmfccc.ca/uploads/4/4/1/7/44170639/dehydration_nations_zine.pdf