Nutrient pollution

In 2009, ecologists determined that along with climate collapse and biodiversity loss, the nutrient pollution of nitrogen and phosphorus was the third of nine planetary boundaries to be crossed by 2009 due to the massive global use of synthetic fertilizers.[1]

Nutrient pollution is one of the most widespread, costly and challenging environmental problems, caused by excess nitrogen and phosphorus in the air and water:

Too much nitrogen and phosphorus in the water causes algae to grow faster than ecosystems can handle. Significant increases in algae harm water quality, food resources and habitats, and decrease the oxygen that fish and other aquatic life need to survive. Large growths of algae are called algal blooms and they can severely reduce or eliminate oxygen in the water, leading to illnesses in fish and the death of large numbers of fish. Some algal blooms are harmful to humans because they produce elevated toxins and bacterial growth that can make people sick if they come into contact with polluted water, consume tainted fish or shellfish, or drink contaminated water.

Nutrient pollution in ground water - which millions of people... use as their drinking water source - can be harmful, even at low levels. Infants are vulnerable to a nitrogen-based compound called nitrates in drinking water. Excess nitrogen in the atmosphere can produce pollutants such as ammonia and ozone, which can impair our ability to breathe, limit visibility and alter plant growth. When excess nitrogen comes back to earth from the atmosphere, it can harm the health of forests, soils and waterways. [2]

Nitrogen Pollution

Sources

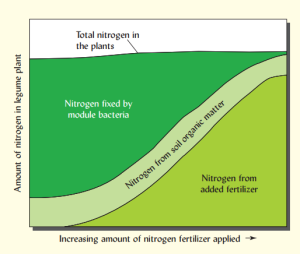

The introduction of nitrogen fertilizers in industrial farming catalyzed a dramatic shift in soil agroecosystems worldwide from organic to inorganic nitrogen. Unlike organic nitrogen, most inorganic nitrogen is easily soluble in water and easily lost to from soils through leaching and volatilization.[3]

Impacts

Human Health

The inorganic nitrogen pollution of ground and surface waters is known to induce a variety of adverse effects on human health:

- Ingested nitrites and nitrates from polluted drinking waters can induce methemoglobinemia in humans, particularly in young infants, by blocking the oxygen-carrying capacity of hemoglobin. Ingested nitrites and nitrates also have a potential role in developing cancers of the digestive tract through their contribution to the formation of nitrosamines.

- In addition, some scientific evidences suggest that ingested nitrites and nitrates might result in mutagenicity, teratogenicity and birth defects, contribute to the risks of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and bladder and ovarian cancers, play a role in the etiology of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and in the development of thyroid hypertrophy, or cause spontaneous abortions and respiratory tract infections.

- Indirect health hazards can occur as a consequence of algal toxins, causing nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, pneumonia, gastroenteritis, hepatoenteritis, muscular cramps, and several poisoning syndromes (paralytic shellfish poisoning, neurotoxic shellfish poisoning, amnesic shellfish poisoning). Other indirect health hazards can also come from the potential relationship between inorganic nitrogen pollution and human infectious diseases (malaria, cholera).[4]

Remedies

Biochar

Due to its fine pore structure and adsorptive capacity, biochar can efficiently adsorb and remove excess inorganic nitrogen and phosphorous from soil, water, and/or waste to control environmental pollution.[5][6]

Ammonium (NH4+): Biochar has been successfully used for ammonium nitrogen adsorption - a major source of water eutrophication and pollution - from wastewater/poultry waste.[7]

Nitrous oxide (N2O): Studies have also found magnetized biochar to be particularly effective in removing excess inorganic nitrogen from soils, preventing the emissions of nitrous oxide, a major greenhouse gas and source of lethal air pollution.[8]

Mycelium

The science behind Mycelium as a mechanism for environmental restoration has not been researched in an extensive manner, likely because of Mycophobia, and has to be deployed with different climate regions in mind,[9] but this provides new possibilities of reversing the destructive effects of climate collapse.

Mycorestoration is the use of fungi to repair or restore the weakened immune systems of environments. Whether habitats have been damaged by human activity or natural disaster, saprophytic, endophytic, mycorrhizal, and in some cases parasitic fungi can aid recovery. As generations of mycelia cycle through a habitat, soil depth and moisture increase, enhancing the carrying capacity of the environment and the diversity of its members. [10]

Mycofiltration

Mycofiltration is the process of using Mycelium as a membrane to filter out microorganisms, pollutants, and silt.[11]

Habitats infused with mycelium reduce downstream particulate flow, mitigate erosion, filter out bacteria and protozoa, and modulate water flow through the soil. More than a mile of threadlike mycelial cells can infuse a gram of soil. These fine filaments function as a cellular net that catches particles and, in some cases, digests them. as the substrate debris is digested, microcavities form and fill with air or water, providing buoyant, aerobic infrastructures with vast surface areas. Water runnoff, rich in organic debris, percolates through the cellular mesh and is cleansed. When water is not flowing, the mycelium channels moisture from afar through its advancing fingerlike cells. [12]

Paul Stamets created a method of utilizing Mycelium to filter downstream water flows/ other sources of water; Using the Mycelium to filter out disease, fecal matter, and other contaminates. The method involves inoculating wood chips or straw bales with Mycelium and placing them around water sources or downstream from contaminated water sources; Choosing best suited strains of mycelium, is necessary, to target specific pathogen carrying insects, like mosquitos, or other contaminates: Staph, coliform, E-coli, and protozoa. [13]

Factory Farms

Factory Farms produce mass animal waste in high concentrations and contain toxic organisms/ disease including Pfiesteria, Listeria, Streptococcus, Escherichia coli, amoebic parasites, and other viruses.[14] [15] [16] A clear example of the threat factory farm waste production poses was when

hurricane Floyd hit North Carolina in 1999, the monsoon like rains caused dikes to burst and manure ponds to overflow, flooding thousands of acres with animal feces and causing incalculable health problems both on and off the farms. Residents in Charlotte were rudely awakened to the enormity of the problems by the fouling on their doorsteps. Filth filled the streets and flooded basements. The collateral damage included contaminated wells, fisheries, and crops. Many diseases spread, including ones pathologists are still at a loss to identify...[17]

Factory Farm waste production also pose risks to Indigenous communities. On the Santee Sioux Reservation cattle ranches produce waste, containing fecal coliform bacteria, which accumulate in septic ponds and leaches into the communities water source. The contaminates from the ranches have made the water undrinkable on the reservation. [18]

Mycelium offers unique solutions to water contamination:

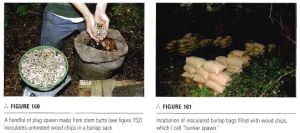

A variety of forms of mycelial mats can prevent downstream pollution. I am keen on using bunker spawn-mycelium in burlap sacks- to build mycelial buffers to capture microbes and nutrients...[19]

Installing a Mycofilter

Paul Stamets explains how easily a mycofiltration system can be installed to help filter contaminates on farmland:

A gently sloped area below a feeding lot or manure pond, where effluent from the lot or pond continually seeps through, is an ideal site to install a mycofilter, essentially a myceliated organic drain field. For the bottom layer, scatter sawdust or wood chips to a depth of 3 to 4 inches. For the first of 2 layers of spawn, on top of the sawdust or wood chips, spread inoculated sawdust by hand or by silage spreader; use 1/4 pound inoculated sawdust per square foot of the site. Next, add a layer of corncobs 4 inches deep, and follow with a second layer of spawn. because high winds and harsh sun can dry out mycofiltration beds, cover the site with waste cardboard before adding the last layer of straw. The finish layer of straw should be 4 to 6 inches deep to provide shade, aeration, and moisture to layers below. (If natural rains do not provide sufficient moisture, sprinklers can be set up for the first few weeks until the site becomes charged with mycelia.) The surface area of the mycofilter should be at least several times larger than the surface area of the manure pond of feeding lot, depending upon depths, slope, and flows.

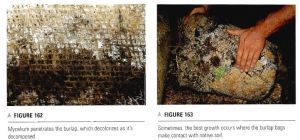

Mycofilters are best built in the early spring. Once established, the mycofilter will mature in a few months and remain viable for years, provided that fresh organic debris is periodically added to the top layer and covered with more straw. For some, the best time for this may be after the fall harvests, when agricultural debris is plentiful. After some time, red worms will arrive and transform the mycelium, cardboard, and debris into rich soil. every 2 to 3 years, the newly emerging material can be scooped up using a front loader tractor and used elsewhere as soil; the timing of this cycle will vary. (Incidentally, gourmet mushrooms may form after rains depending upon temperatures. These mushrooms "reseed" the beds, provided there is enough food.)...

... I encourage farmers to try this method. The amount of time to install a mycofilter is minimal, only a couple hours. Spawn will probably be your biggest expense, but once established and cared for, the mycelium can regenerate itself until the debris base has been reduced to soil. As these areas mature, they usually become covered with native grasses, which also play remediative roles. A universe of compatible organisms shares this habitat, with mushroom mycelia reigning as the pioneering organisms.[20]

Burlap Bunker Spawn

Paul Stamets created a method of Mycofiltration utilizing Burlap bags filled with mycelium spawn and other organic materials such as wood chips. The burlap sacks can then be placed between different environments and aid in the filtering of contaminates and other small organic matter. The burlap sacks also aid in the prevention of erosion.

Immediately upon construction, these spawn bags filter biological or chemical wastes and prevent downstream contamination due to the uncolonized wood chips' extensive surface areas and absorptive abilities. As the mycelium grows, its net-like cells increasingly trap silt and bacteria, and the "sweat" of the mycelium denatures many toxins, both chemical and biological. Upon colonization, a burlap bag of spawn (now weighing 30 to 60 pounds) becomes a mycofiltration vessel that can also be put to work for habitat restoration or can be staged for further expansion of mycelium into more wood chip-filled burlap sacks.[21]

Phytoremediation

Qannabis

https://sci-hub.ru/https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12010-011-9382-0#page-2

Sunflowers

Cattails

Legumes

Sources

- ↑ https://commondreams.org/reaching-1-5c-global-heating

- ↑ https://www.epa.gov/nutrientpollution/issue

- ↑ https://www.pearsonhighered.com/assets/samplechapter/0/1/3/3/0133254488.pdf

- ↑ https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0160412006000602

- ↑ https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S095965262030620X

- ↑ https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0048969718344796

- ↑ https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Arvind_Singh56/post/What_is_remove_biochar_in_wastewater_treatment/attachment/59fb0fda4cde26d68ce667f6/AS%3A556225152262144%401509625818342/download/Ammoniumnitrogenremovalfromwastewaterbybiocharadsorption.pdf

- ↑ https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048969721065189

- ↑ https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4441/10/9/1226/htm

- ↑ Paul Stamets, Mycelium Running, Page 55

- ↑ https://assets.fungiperfecti.net/pdf/articles/Fungi_Perfecti_Phase_I_Report.pdf

- ↑ Paul Stamets, Mycelium Running, Page 58

- ↑ https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0925857414002250

- ↑ https://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/doi/pdf/10.1289/ehp.02110445

- ↑ Paul Stamets, Mycelium Running, Page 63

- ↑ https://branchoutnow.org/coronavirus-and-the-climate-a-singular-crisis/

- ↑ Paul Stamets, Mycelium Running, Page 63-64

- ↑ https://branchoutnow.org/growing-sovereignty-part-2-regenerating-sacred-water/

- ↑ Paul Stamets, Mycelium Running, Page 64

- ↑ Paul Stamets, Mycelium Running, Page 68

- ↑ Paul Stamets, Mycelium Running, Page 151