Forestgarden

Summary

Hempforestry

Turtle Island

As across almost all of the so-called United States the original settlers viewed the land as a wild untouched landscape absent of human intervention or cultivation. As time has gone on the western scientific communities are now realizing vast amounts of land across Turtle Island were managed and tended to including many plants considered "wild."[1]

Fist Nations in the North West

Many Nations in the North West of Turtle Island (Cascadia bioregion), such as the Tsm'syen and Coast Salish First Nations, have cultivated forest gardens for thousands of years.[2]The two nations listed above would clear spots next to native coniferous forests and plant perennial species and shrubs including: Crabapple, Wild Cherry, Plum, Soapberry, Wild ginger, Rice Roots, and medicinal herbs. The Nations would collect and transplant the plants while utilizing many techniques to keep the forest garden healthy such as pruning, fertilizing, coppicing, and controlled burns.[3]

Colorado Plateau

https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2025047118#sec-2

Hazelnut in Motion

There is a fleeting ethnographic record of hazelnut in so-called British Columbia, however shell fragments can be found archaeologically throughout the province. Linguistic evidence also supports the hypothesis that long distance transplanting of hazelnut, from the Salish region to the Ts'msyen, Gitxsan and Wet'suwet’en regions resulted in ecologically disjunct populations (e.g., in Hazelton BC, hence the name). Hazelnut was traditionally managed by fire and has numerous uses for people including for food (nut), for fuel (oily shells), it was an important medicine, the root produced an intense blue dye, and young switches were used for weaving and construction. ...[4]

Beaked hazelnut and the closely related American hazelnut (C. americana Walt.) are valued as food and medicinal plants for Indigenous peoples across North America and were used by Algonquin, Cree, Mi’kmaq, and Maliseet peoples, and by many groups of British Columbia, including Straits Salish, Halq’eméylem, Squamish, and Nuu-chah-nulth on the Coast, and Nlaka’pamux, Stl’atl’imx (Lillooet), Syilx (Okanagan-Colville), Secwepemc (Shuswap), Ktunaxa (Kootenay) in the BC Interior, and the Nisga’a and Gitxsan in the north, as well as by virtually all Indigenous peoples of Western Washington.[1]

Residential schools and ongoing colonialism have disrupted and in some cases erased deep place-based agriculture practices and for hazelnut the same is true.[1]

Squirrels

Squirrels depending on the nation are considered 'pesky' or 'helpful.' During interviews for a study[5] one of the interviewees, Elder Wal’ceckwu (Marion Dixon) from the Nlaka’pamux Nation, explained:

...to get them away you pick a whole bunch, the left-overs from last year that are not in the wrappers [involucres] anymore. We take them and we a dig a little trench far away from the trees where we had our bushes and then, we put them over there so the squirrels are all busy over there while we’re [picking]...[1]

This practice is a clear example of Traditional Ecological Knowledge through observation a symbiotic solution to squirrels taking hazelnuts is created and deployed.

Other nations view the squirrels as helpers:

In northern BC, some Gitxsan people had their own means for dealing with squirrels. Sim’oogit (Chief) T’enim Gyet (Art Matthews) remembers:

"...the squirrels help us…we don’t pick [the hazelnut], we cheat. We wait for the squirrels to clean and cache them so we don’t have to."[1]

Hazelnut Benefits

Hazelnuts are a high source of protein and are rich in unsaturated fats. They are a significant source of thiamine and vitamin B6 and other B vitamins. They can be eaten raw and stored for years without spoiling. Like Marion, Gitxsan Elders in northern BC remember hazelnut as a Christmas food, no doubt because nuts would keep for months when fresh food was scarce. Nuts were collected en masse and either left to dry as is (involucres can rot off the shells without turning the nut) or de-husked and processed all at once. Wintu people in California used willow switches to beat the involucres off the kernel. Marion recalls the hard work involved in collecting and processing nuts:

"When they’re ready, we pick a whole bunch of them and we’d put them in a basket or a box or whatever we had. And we get them dry. And we would sit there for days, and days, and days, cause we used to have bags and boxes and baskets of them, and then one day when its raining or snowing outside, I had my own little hammer and I’d sit there and break them, pick shells off them, and put them in the thing [a storage basket] and then my grandmother would prepare them… but it took days and days and days to pick them, never mind opening them and days and days to preserve them [when made into an oil], but then we could use them as we want to."[1]

Lasting Legacy of Indigenous Forest Management

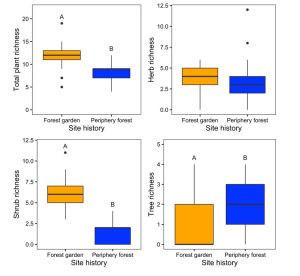

Our findings highlight that historical Indigenous land-use legacies can support long-persisting (e.g., 150+ years) high functional and taxonomic plant diversity relative to less intensively utilized or managed landscapes nearby. Notably, this contrasts with most studies of land-use legacies of human impact which often find negative effects from human influences (e.g., industrial land-use). The taxonomic diversity of forest gardens in our study region is similar to that in biodiversity studies of Indigenous village sites and forest gardens in other parts of the world, including the Amazonian neotropics, eastern Mexico, and northwestern Belize, where people increased the diversity of desired food plants or overall landscape (beta) diversity. This research builds on an increasing awareness among scientists that biodiverse ecosystems globally have been formed and maintained by Indigenous peoples. There is therefore a greater need to understand the role of Indigenous management practices, including their impacts and effects, and to comprehend the many variables that support the resilience and other functions of managed forest systems.[7]

Cited

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Armstrong, C. G., Dixon, W. M., & Turner, N. J. (2018). Management and Traditional Production of Beaked Hazelnut (k’áp’xw-az’, Corylus cornuta; Betulaceae) in British Columbia. Human Ecology. doi:10.1007/s10745-018-0015-x

- ↑ Leopold EB, Boyd R. 1999. An Ecological History of Old Prairie Areas in Southwestern Washington. Pages 139–163 in Boyd R eds. Indians, Fire and the Land in the Pacific Northwest. Oregon State University Press

- ↑ https://arstechnica.com/science/2021/05/indigenous-forest-gardens-remain-productive-and-diverse-for-over-a-century/

- ↑ https://www.chelseygeralda.com/traditional-hazelnut-management

- ↑ https://www.chelseygeralda.com/traditional-hazelnut-management

- ↑ https://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol26/iss2/art6/

- ↑ https://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol26/iss2/art6/#discussion14