Food Sovereignty

Although it was first developed to challenge the neoliberal globalisation being promoted by the World Trade Organization (WTO), the influence of the concept of food sovereignty has grown because it offers a different way of thinking about how the world food system can be organised; it offers an alternative. As developed initially by Via Campesina and further elaborated at the 2007 Nyéléni Forum for Food Sovereignty, food sovereignty is based on the right of peoples and countries to define their own agricultural and food policy and has five interlinked and inseparable components:

(1) A focus on food for people: food sovereignty puts the right to sufficient, healthy and culturally appropriate food for all individuals, peoples and communities at the centre of food, agriculture, livestock and fisheries policies, and rejects the proposition that food is just another commodity.

(2) The valuing of food providers: food sovereignty values and supports the contributions, and respects the rights, of women and men who grow, harvest and process food and rejects those policies, actions and programmes that undervalue them and threaten their livelihoods.

(3) Localisation of food systems: food sovereignty puts food providers and food consumers at the centre of decision making on food issues; protects providers from the dumping of food in local markets; protects consumers from poor quality and unhealthy food, including food tainted with transgenic organisms; and rejects governance structures that depend on inequitable international trade and give power to corporations. It places control over territory, land, grazing, water, seeds, livestock and fish populations in the hands of local food providers and respects their rights to use and share them in socially and environmentally sustainable ways; it promotes positive interaction between food providers in different territories and from different sectors, which helps resolve conflicts; and rejects the privatisation of natural resources through laws, commercial contracts and intellectual property rights regimes.

(4) The building of knowledge and skills: food sovereignty builds on the skills and local knowledge of food providers and their local organisations that conserve, develop and manage localised food production and harvesting systems, developing appropriate research systems to support this, and rejects technologies that undermine these.

(5) Working with nature: food sovereignty uses the contributions of nature in diverse, low external-input agroecological production and harvesting methods that maximise the contribution of ecosystems and improve resilience. It rejects methods that harm ecosystem functions, and which depend on energy-intensive monocultures and livestock factories and other industrialised production methods. [1] [2]

Commons Transition

A commons transition is a multi-faceted strategy to transition away from capitalism and industrial agriculture, including food, seed, and knowledge commons. Many organizations and groups of people have already begun constructing these commons to begin the transition away from the capitalist market-relations which view everything as a potential product to abstract and commodify, including food, water, seed and land.

United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

La Vía Campesina

"La Via Campesina is a transnational movement that represents the grievances and demands of farmers from around the world whose lives have been disrupted by globalization. This movement and the 200 million small-scale farmers around the world it has mobilized are a powerful demonstration of the fact that not everyone feels that they have been served well by economic globalization."[3]

La Vía Campesina, a network of 182 peasant organizations that now brings together over 200 million peasants across 81 countries and five continents, has been at the centre of the emergence of food sovereignty. As a network that was transnational from its inception, La Vía Campesina brings together movements that are inspired by a range of practices and ideological perspectives: liberation theology and education, indigenous modes of conflict resolution, deep ecology, feminist praxis, agrarian Marxism, anarchist organizing principles, and more liberal approaches to reform and advocacy, to name a few. Despite this diversity, La Vía Campesina has overcome the fragmentation so common amongst social movements.[4]

Despite La Vía Campesina being arguably the largest social movement in the world discussions about the organization is rarely if ever mentioned in textbooks or talked about by mainstream corporate media:

"One of the reasons textbooks fail to include discussions of La Vía Campesina — and other social movements, for that matter — is because the publishers presume that change comes from the top. Textbooks teach students to look to Great Individuals, governments, corporations, multilateral organizations, the United Nations. According to the official stories offered in textbooks, power flows downhill, from the commanding heights. Another source of La Vía Campesina’s invisibility is textbooks’ core narrative — that humanity is in the midst of a pageant of progress, powered by science, technology, and capitalism. Peasants, by contrast, represent backwardness, pockets of ancient history waiting around in the countryside for the beneficent arrival of the modern world."[5]

Just Transition

"We must build visionary economy that is very different than the one we now are in. This requires stopping the bad while at the same time as building the new. We must change the rules to redistribute resources and power to local communities. Just transition initiatives are shifting from dirty energy to energy democracy, from funding highways to expanding public transit, from incinerators and landfills to zero waste, from industrial food systems to food sovereignty, from gentrification to community land rights, from military violence to peaceful resolution, and from rampant destructive development to ecosystem restoration. Core to a just transition is deep democracy in which workers and communities have control over the decisions that affect their daily lives.

To liberate the soil and to liberate our souls we must decolonize our imaginations, remember our way forward and divorce ourselves from the comforts of empire. We must trust that deep in our cultures and ancestries is the diverse wisdom we need to navigate our way towards a world where we live in just relationships with each other and with the earth."[6]

Dr. Vandana Shiva outlines nine steps necessary for a just transition away from the status quo production of food as a commodity via chemical intensive Industrial Agriculture. The steps are:

The first transition is from fiction to reality: Moving away from the idea of corporations being people and recognizing there are real people everywhere that are facing nutritional crisis and there are people that can grow food everywhere. "Whereas the rise of industrial agriculture was based on the removal of people from the land, the emergence of the new agriculture paradigm is based on returning to the dirt, to the Earth, and to the soil: in cities and in schools, on terraces and on walls. There is no person who cannot grow food, and part of being fully human is reconnecting to the Earth and its communities."[7] Farming and Gardening can become revolutions everywhere as people begin to create real food systems made to protect the Earth and People.

The second transition is from mechanistic, reductionist science to an agroecological science based on relationships and interconnectedness: "It is the recognition that soil, seed, water, farmers, and our bodies are intelligent beings, not dead matter or machines... The old universities teaching chemical warfare as agricultural expertise are being replaced by farms servings as schools, where the knowledge of real farming to produce real food is growing. A transition away from the rule of corporations and profits is also a knowledge transition toward the emerging scientific paradigm of agroecology"[8] This new paradigm requires a knowledge commons where ideas, methods, and techniques can be openly accessed and shared. As we grow this knowledge commons the interconnectedness needed to proliferate agroecology will expand.

The third transition is from seed as the "intellectual property" of corporations to seed as living, diverse, and evolving: toward seed as the commons that is the source of food and the source of life: "The creation of community seed banks and seed libraries is part of the movements for seed freedom that are resisting the imposition of unscientific and unjust seed laws based on uniformity. Also part of this resistance are the scientific movements innovating with participatory and evolutionary breeding, which are offering successful and superior alternatives to industrial breeding."[9]

The fourth transition is from chemical intensification to biodiversity intensification and ecological intensification, and from monocultures to diversity: This involves removing chemicals and toxins as the main input into agriculture to chemical-free, agroecological systems. "This transition must also move away from the fiction of "high yield" to the reality of diverse systems outputs, including quantity, quality, taste, health, and nutrition. Not only are biodiverse agricultural systems more productive and resilient, biodiverse food systems are the best insurance against diseases linked to nutritional deficiencies..."[10]

The fifth transition is from pseudoproductivity to real productivity: This involves the decommodification of food and analyzing the cost of social, health, and ecological costs of chemical-, capital-, and fossil-fuel-intensive industrial agriculture, as well as the benefits of ecological agriculture for public health, social cohesion, and ecological sustainability. "... A real productivity calculus recognizes farmers' rights. In an ecological and living world, farmers are not just producers of food; they are conservators and builders of biodiversity and a stable climate, they are providers of health, and they are custodians of our diverse and collective cultures."[11] Agroecological food sovereignty projects around the world are working on creating this framework path towards transitioning away from industrial agriculture.

The sixth transition is from fake food to real food, from food that destroys our health to food that nourishes our bodies and minds: "This is also a transition from food as a commodity produced for profits to food as the most important source of health and well-being. The entire food and agricultural system treats food as a commodity to be produced, processesd, and traded solely to maximize corporate profits. The highest use value of food is in providing health and nourishment, and the primary contribution of food is to public health, not corporate profits. Commodities are based on quantity alone, irrespective of whether they are nutritionally empty or full of toxins and poisons. Food as a tradable commodity loses its use value of nourishment."[12]

The seventh transition is from the obsession with "big" to a nurturing of "small," from the global to the local: "Large-scale, long-distance food chains in an industrialized, globalized food system must become a small-scale, short-distance food web based on the ecological enlightenment that no place is too small to produce food. Everyone is an eater, and everyone has the right to healthy, safe food with the smallest ecological footprint. Everyone can also be a grower of food, which means that food can and must be grown everywhere." [13] A common argument for industrial agriculture is that large scale production is needed to feed people living in large cities. Dr.Shiva addresses this concern three fold:

1) "... large-scale farms are not producing food; they are producing commodities. Commodities do not feed people."

2) "... every city should have its own "foodshed" that supplies most of its food needs in the same way that cities have "watersheds" that supply water. Larger cities can have larger foodsheds. Planning for food needs, as well as integrating the city and the countryside through good food, should be part of Urban Planning.

3) ... "the new food and agricultural movement is exploding in cities. Urban communities are reclaiming the food system through urban gardens, community gardens, school gardens, and gardens on terraces and balconies and walls. No place is too small to nourish a plant that can nourish us."[14]

The eighth transition is from false, manipulated, and fictitious prices based on the Law of Exploitation to real and just prices based on the Law of Return: "In rich countries, citizens are questioning "cheap" food and what an over consumption of this food means for people's health. In poor countries, there are riots and protests and changes in regimes because of rising prices of food linked to free market polices. The Egyptian "Arab Spring," for example, started because of the rising prices of bread. Both the "cheap" food in rich countries and the rising costs of food in poor countries are based on a food system that puts profits about the rights of people to healthy, safe, and affordable food. This is based on the manipulation of prices by corporate giants and financial institutions through subsidies in rich countries, financial speculation, and betting on agriculture. Fair trade initiatives, on the other hand, allow farmers to get a fair and just return for their contributions to health and planetary care."

Dr. Vandana Shiva continues:

"The price of anything should reflect its true cost and true benefits: the high costs of ecological degradation and damage to people's health in the case of chemical-intensive industrial agriculture, and the positive contributions of ecological agriculture to rejuvenating the soil, considering biodiversity and water, mitigating climate change, and providing healthy, nutritious food." [15]

The ninth transition is from the false idea of competition to the reality of cooperation: "The entire edifice of industrial production, free trade, and globalization is based on competition as a virtue, as an essential human trait. Plants are put into competition with one another and with insects, including pollinators. Farmers are pitted against one another and against consumers, and every country is in competition with every other country through chasing investment performance and through trade wars. Competition creates a downward spiral from the perspective of the planet and people, and an upward spike for corporate profits. But the ultimate consequence of competition is collapse."

Dr. Vandana Shiva continues:

"The reality of the web of life is cooperation: from the tiniest cell and microorganism to the largest mammal. Cooperation between diverse species increases food production and controls pests and weeds. Cooperation between people creates communities and living economics that maximize human welfare, including, livelihoods, and minimze industry's profits. Cooperative systems are based on the Law of Return. They create sustainability, justice, and peace. In times of collapse, cooperation is a survival imperative."[16]

Food Commons

Knowledge Commons

A major challenge facing the climate movement is the knowledge-action gap. It would be a mistake to separate from knowledge commons practical knowledge, especially knowledge embodied in practice. Taken together, such collective action, or mass climate action, is the practical realization of climate knowledge commons relative to their essential purpose.

In Red Alert, Dr Wildcat describes how Indigenous ingenuity or indigenuity addresses this dilemma:

The ability to solve pressing life issues facing humankind now by situating our solutions in Earth-based local Indigenous deep spatial knowledges of tribal peoples - constitutes a practical merger of knowing with doing. Their lifeways embody knowing as doing... an ability to work with what they have available and the wisdom to ensure, such as they can, that they can continue doing it.

Conversely, what "Western" society lacks but so desperately needs is "practical knowledge about living well brought about by a lifetime of attentiveness to something other than our own human-produced culture."[17]

Ultimately, this approach aligns with adopting the most advanced complexity models of experimental science concerning the current situation of global burning or climate collapse:

By doing so, we might move away from thinking about a single solution for the problem we face and toward thinking about our participating in an emerging world where we do not wring our hands and fail to act, but act even in little ways, in personal choices, to contribute to emerging systems - in other words, societal properties - that might slow the accelerating decline in the diversity of life we are now witnessing.[18]

Placed Based Knowledge

Under a food sovereignty framework having a deep understanding and relationship with local environments is tantamount to building a knowledge commons and transmitting the knowledge to our neighbors and unto future generations. Under the current paradigm of industrialized food production a mechanical 'one size fits all' method is employed across the planet ignoring the native species and techniques that have/should be employed under specific localized conditions. This mechanical lens has detrimental effects on the planet and are not nearly as productive as working with native species within a deep agroecological place-based framework.[19] Traditional Ecological Knowledge has been employed by Indigenous Nations since time immemorial and provides this framework necessary to transition away from capitalism and industrial agriculture. Winona LaDuke explains this concept:

"Minobimaatisiiwin," or the "good life," is the basic objective of the Anishinabeg and Cree people who have historically, and to this day, occupied a great portion of the north-central region of the North American continent. An alternative interpretation of the word is "continuous rebirth." This is how we traditionally understand the world and how indigenous societies have come to live within natural law. Two tenets are essential to this paradigm: cyclical thinking and reciprocal relations and responsibilities to the Earth and creation. Cyclical thinking, common to most indigenous or land-based cultures and value systems, is an understanding that the world (time, and all parts of the natural order-including the moon, the tides, women, lives, seasons, or age) flows in cycles. Within this understanding is a clear sense of birth and rebirth and a knowledge that what one does today will affect one in the future, on the return. A second concept, reciprocal relations, defines responsibilities and ways of relating between humans and the ecosystem. Simply stated, the resources of the economic system, whether they be wild rice or deer, are recognized as animate and, as such, gifts from the Creator. Within that context, one could not take life without a reciprocal offering, usually tobacco or some other recognition of the Anishinabeg's reliance on the Creator. There must always be this reciprocity. Additionally, assumed in the "code of ethics" is an understanding that "you take only what you need, and you leave the rest."[20]

Blood Knowledge

Blood Knowledge is a concept Audrey Logan teaches at her permaculture based Klinic Garden, and it is the idea that everyone has the knowledge to grow food within their DNA and it has been passed down over many generations. One just has to access this knowledge through action, which simply means growing food. Reconnecting with the ancient knowledge ingrained into everyone's DNA is an important aspect of a commons transition and important to building a knowledge commons.

Blood knowledge is a path towards true food sovereignty through the recognition that we are all potential stewards of the earth and can all contribute to the production of local healthy food. Auntie explains the concept of blood knowledge in her zine:

I want to make sure to claim the knowledge of what I learned on my own as being my own knowledge... So blood knowledge, as we now know, the DNA of our grandmothers are in us when our mothers carry us, and everyone has it, it’s in our DNA...

We have a lot of young kids, they have it in their genes, their blood, but if they don’t acknowledge it and if they think that they can’t get it because they haven’t gotten it through their ancestors that they could never meet because of a system of separation— that would be wrong. But they can actually hear their ancestors who are there with them, their voices— if they learn to listen. There are times when auntie speaks, when I hear her, and i’m like ‘whoah!’ And when I was younger that was called crazy. But now we know it’s not craziness, it’s connection.[21]

Seed Commons

Research published by the International Journal of the Commons identified four criteria that characterize diverse seed commons[22][23]:

(1) Collective responsibility: by supporting the right to use, multiply, share, and develop seeds freely, seed commons involve diverse participants working together in strengthening and protecting agro-biodiversity

(2) Protection from enclosure: safeguarding against legal and bio-technological enclosures, such as private intellectual property rights (patents on varieties) and the increasing use of seeds with bio-technological restrictions prohibiting their reproduction

(3) Decentralized management: with collectively devised rules, norms, and shared practices for the management of seeds agreed upon collectively at the communal level, decentral sub-structures can also hold independent decision-making power to support (bio)regional adaptation and local place-based knowledge

(4) Sharing of knowledge: encompassing both the sharing of formal knowledge with regard to all steps of the breeding and cultivation process, and the sharing of practical knowledge - specifically practical skills in breeding, seed multiplication and plant cultivation

From the principle of seed freedom to practices of saving seed and building a food community, Dr. Vandana Shiva outlines the revolutionary potential of the seed commons:

Let us reclaim our Seed Freedom. Seed Freedom is freedom to live with other beings who have a right to live, thrive and flourish. Saving seed has been our highest duty in the past, and must become our first duty in the present and future. From the duty to save seeds and biodiversity flow our rights to life and livelihood, food and health. From our duty to defend the freedom of seed to evolve, multiply and be shared flows our seed freedom and food freedom. Save your seeds, in a pot in your windowsill, in your garden, in a community seed bank or seed library, on living farmers. Reclaiming our seed commons is reclaiming the future of humans and all species.

Food begins as seed. Grow nutrition, Grow health. Grow real living food from real living seed. In your window, your balcony, your terrace, your garden. Create a food community so you know your food, you know the community that grew it. Growing and Eating real food for health is a revolution each of us can start. Each of us must start.[24]

Seed Freedom

Dr.Vandana Shiva elaborates on what seed freedom looks like:

We use the term "seed freedom" to talk about the right of the seed as a living, self-organized system that can evolve freely without the threat of extinction, genetic contamination, or termination through technologies designed to make seeds sterile. Seed freedom is the freedom of bees to pollinate freely, without threat of extinction due to poisons. Seed freedom is the freedom of the web of life to weave itself in integrity and resilience, fostering interconnectedness and well-being for all. Seed freedom is the right of farmers to save, exchange, breed, and sell farmers' varities-- seeds that have been evolved over milennia-- without interference by the state or by corporations. Seed freedom is the freedom of eaters to have access to food grown from seeds bred for diversity, taste, flavor, quality, and nutrtion[25]

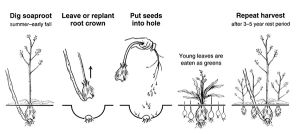

Living Seed Banks

The Klinic Garden is a prime example of a living seed bank- Where not all of the plants are harvested, but rather are allowed to grow to seed. Allowing plants to grow until they seed enables the plants to naturally self-seed themselves and naturally reproduce more plants.

Localization

The production of healthy, sustainable food by local farmers and workers is fundamental to transition away from globalized neoliberal industrial agriculture.[26] Within the broader framework of food sovereignty, localized food production is a key part of this movement's recipe challenging the dominant position of massive industrial ag corporations in the global food economy.[27]

As localization and its connection to food sovereignty are not static, but dynamic, it is important to determine if local food producers are contributing to a broader movement of food sovereignty. Small farm projects are often viewed as inherently antithetical to industrialized agriculture/capitalism, but small scale farmers can also employ similar methods of production as industrial agriculture. Beyond simply producing food locally it's key to note that:

Local food initiatives established with agroecological production methods fall more fully within the food sovereignty framework. Agroecology is based on enhancing small-scale farm productivity while conserving ecological resources through engagement in deeply rooted traditional practices and scientific knowledge of ecological processes. Rosset et al summarise agroecology as a set of principles that include soil conservation and soil building, recycling of nutrients, poly-cropping and biodiversity preservation, and the use of biological mechanisms for pest control. While agroecology practice is spreading through food sovereignty networks, questions remain about whether enough food can be produced, at affordable prices, to feed everyone. [28]

Localized food production, theoretically, decreases the distance food must travel to reach consumers. The decrease of distance does not necessarily end the commodification of food, but it does present the potential to end the abstraction of food into uniform mass produced commodities, which have no tangible connections between the producer and consumer.[29][30] Dr. Vandana Shiva discusses the abstraction of food within a capitalist society versus local food producers focusing on food sovereignty:

There are two kinds of markets. Markets embedded in nature and society are places of exchange, of meeting, of culture. Some are simultaneously cultural festivals and spaces for economic transactions, with real people buying and selling real things they have produced or directly need. Such markets are diverse and direct. They serve people, and are shaped by people.

The market shaped by capital, excludes people as producers. Cultural spaces of exchange are replaced by invisible processes. People's needs are substituted for by greed, profit, and consumerism. The market becomes the mystification of processes of crude capital accumulation, the mask behind which those wielding corporate power hide.

It is this disembodied, decontextualized market which destroys the environment and peoples' lives.[31]

Another challenge undermining the sovereignty of localized food production is the dispossession of farmers from their land[32] - today, a result of neoliberal capitalism and its leg of industrialized agriculture. This dispossession happens to small scale sustainable farmers and farmers trapped within the industrial agricultural business, which makes it difficult to exit due to costly inputs such as fertilizer and expensive large scale farm equipment necessary to plant, grow and harvest large monocultures:[33]

...Dispossession not only occurs to those caught struggling against the imposition of cheap imports flooding their national and local markets, it also happens to those who engage and participate in the same industrial food system that is eventually responsible for their dispossession. The dispossessed may be ‘adversely incorporated’ into the global food system, where they are marginalised and exploited,79 for example as migrant labourers on highly industrialised, single commodity-driven farms or as contract farmers integrated into corporate production systems. Participation is often forced by the search for higher yields to offset low prices or the consolidation of processers who prefer to contract production on their terms or by the difficulty of unhooking from the industrial system once you are connected to it through inputs and other means.[34]

Metabolic Rift

Historians have argued that the first instances of agricultural domestication, allegedly around 10,000 years ago, triggered an irreversible trend of human domination over nature.[35] This historical analysis does not take into account multiple sites of agricultural domestication across the so called Americas dating before colonization and its genocidal destruction came its shores.[36] Ignoring these pre-colonial sites of agriculture does not consider how Capitalism affected agricultural production and assumes that the process of domestication within itself led to the alienation of nature from humanity. Karl Marx created the idea of the metabolic rift and it explains:

...the concept of a socio-ecological exchange or metabolism as a dynamic and interdependent process linking society to nature through labour: members of society appropriate the materials of nature through labour, in the process transforming the environment and simultaneously their own (human) nature. The socio-ecological metabolism in agriculture is maintained over time and space through the recycling of nutrients. Formerly small-scale, local agricultural initiatives took nutrients from the soil in the form of food, fodder, and fibre, later replenishing soil fertility with wastes to ensure continued productivity.... ....This theoretically sustainable, metabolic relationship between society and nature prior to the advent of capitalism was broken by the creation of labour markets and the commodification of nature, and of land in particular. The widening separation of rural producers from urban consumers disrupted traditional nutrient cycling, causing extensive soil depletion and an increasing dependence on imported fertilizers...[37]

As capitalism expanded, the relationship between humans, production, and nature transformed as well, creating more and more distance between consumers and producers. Through this distance, ecological symbiosis was replaced with market relations resulting in commodification of the land, which over time would transform into monocultured industrialized agriculture. Capitalist expansion ruptured a sustainable metabolic rift,

... which resulted in unforeseen, if not entirely unintended, consequences. Water pollution, deforestation, and over time, food crises were all characteristics of transformed land and labour markets. Subsequent social and economic disruptions associated with waves of capitalist expansion and the Industrial Revolution further reorganised the landscape of production and engendered systemic cycles of agroecological transformation (Foster 1999, 2000, Moore 2000).[38]

Industrialized agriculture required a decrease in seed varieties and streamlined production to maximize commodity profits.[39] The homogenization and scaling down of genetic diversity facilitated and required increased inputs of chemical fertilizers to replenish depleted soil, which has led to water pollution, desertification, and soil degradation.[40][41] The decrease in genetic diversity caused crops to become less resistant to pests, predators, and disease.[42] All of these factors have led to the globalized food system becoming far less resilient to disturbances, which are becoming more frequent as industrial agriculture continues to massively contribute to climate collapse and ecocide.[43] [44]

Reestablishing a symbiotic metabolic rift between humanity and nature requires recognizing they are both inextricably linked.[45] Understanding the metabolic rift in conjunction with localized food production within a food sovereignty framework helps provide a path forward away from industrialized agriculture toward food justice and true food sovereignty.

Agroecology

Agroecology is the application of ecological concepts, the study of relationships between plants, animals, people, and their environment - and the balance between these relationships and principles in farming.[46] "The term “agroecology” was first used in 1928 by a Russian agronomist, Basil M. Bensin (1881–1973), to designate an approach to agronomy that draws on ecological knowledge by considering living organisms as a “system” of interacting and dynamic communities"[47] Agroecological and permaculture techniques have long been established by Indigenous Nations across Turtle Island and across the world as a whole before colonization. The reinvigoration of interest into sustainable methods of agriculture are simply a continuation of Indigenous techniques.

In the context of food sovereignty and localization utilizing agroecology is key[48] [49] to transitioning away from and repairing the destructive effects[50] of industrial agriculture.[51] Agroecology is gaining momentum across the globe, in part, because of the Green Revolution's impacts on the environment and its inability to sustainably provide food for the world:

From the agricultural model promoted by the green revolution to that of agroecology, people are moving from a prescriptive “top-down” logic of technical change, based on the implementation of standardized technical packages, to an innovation logic supported by a network of various stakeholders, including the farmers themselves, based on the analysis of local contexts and needs, and the development of the most appropriate biological, technical and institutional solutions on a territorial scale.[52]

Deep Agroecology

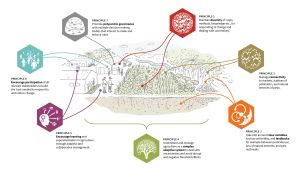

Is a method of agroecology that is more than just a sustainable method of growing food, but rather a comprehensive framework for implementing agroecological concepts in a way that does not simply reproduce the same capitalist market-relations present in the status quo:

Deep agroecology promotes participatory research, responsible consumerism, mutualist financing of agriculture that involves consumers, and finally a reform of public agricultural policies, particularly in terms of taxation, market regulation, autonomy and the empowerment of local communities. More than an ecological adjustment of farming practices, it is a major component of food sovereignty, which considers the enhancement of agro-biodiversity as the entry point for redesigning systems that ensure farmers’ autonomy and food sovereignty. This food sovereignty expresses the needs and aspirations of farmers and local communities. It refers to the right of people to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, as well as their right to define their own agricultural and food systems. This implies the autonomy of seeds, which are the first link in the food chain.[53]

Deep Agroecology more closely resembles methods of agriculture employed by Indigenous Nations prior to European colonization, because it is a framework that views the world as a whole and recognizes the inter-connection of all beings on Earth- Human or otherwise.

Small Farm Food Production

Around 70% of the world is fed by small-scale farmers and other peasants.[54] The International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) estimated that small producers provide 80% of food in large parts of the developing world. [55] A paper published by the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) in 2021 made the claim that small farms only feed about one third of the world’s population.[56] In response:

Eight organisations with long experience working on food and farming issues, including ETC Group and GRAIN, have now written to FAO Director General QU Dongyu, sharply criticizing the UN food agency for spreading confusing data. The open letter calls upon FAO to examine its methodology, clarify itself and to reaffirm that peasants (including small farmers, artisanal fishers, pastoralists, hunters and gatherers, and urban producers) not only provide more food with fewer resources but are the primary source of nourishment for at least 70% of the world population.[57]

Dr.Vandana Shiva speaks on the myth of small farms and small scale-farmers having lower rates of production:

We have seen, small, biodiverse farms are more ecologically efficient than large industrial monocultures. When one recognizes that small farms across the world produce greater and more diverse outputs of nutritious crops, it becomes clear that industrial breeding has actually reduced food security. Industrial farming has created hunger and poverty; yet large industrial farms are justified as necessary in order to produce more food....

...Small farms produce more food than large industrial farms because small-scale farmers give more care to the soil, plants, and animals, and they intensify biodiversity, not external chemical inputs. As farms increase in size, they replace labor with fossil fuels for farm machinery, the caring work of farmers with toxic chemicals, and the intelligence of nature and farmers with careless technologies.

...What is growing on large farms is not food; it is commodities. For example, only 10 percent of the corn and soy taking over world agriculture is eaten. Ninety percent goes to drive cars as biofuel, or to feed animals being tortured in factory farms.[58]

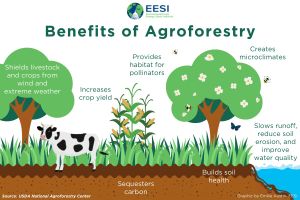

Agroforestry

Agroforestry is a land management technique, thousands of years old,[59] utilizing the symbiotic relationship between trees and food crops. Agroforestry began to be recognized and incorporated into national research and development agendas in many developing countries during the 1980s and 1990s.[60] Trees can provide vital habitats for wildlife-housing natural predators of commons pests, thus reducing the need for pesticides.[61] Trees can also help reduce soil erosion, and can help absorb polluted water, so it doesn't reach rivers, streams, or our oceans.[62] [63] Agroforestry can aid in carbon sequestration through above & below ground biomass and can aid in enhancing soil productivity through biological nitrogen fixation, efficient nutrient cycling, and deep capture of nutrients. [64] Other types of agroforestry include hedgerows and buffer strips, forest farming - cultivation within a forest environment, and home gardens for agroforestry on small scales in mixed or urban settings. Studies on the efficacy of Agroforestry are limited, so more research is needed to provide farmers, and other individuals, with the necessary knowledge to adopt said techniques to their specific weather regions.[65]

Silvo-pastoral agroforestry

Is an agroforesty technique involving animals grazing underneath trees which provides nutrients for the soil and shelter for the animals.

Silvo-arable agroforestry

Crops are grown underneath trees where the roots of the trees are deeper than the crop plants.

Indigenous nations pre-colonization practiced both of the aforementioned methods of agroforestry.[66]

Indigenous Food Sovereignty

Legacies of Indigenous Food Sovereignty offer many pathways to achieve food sovereignty for everyone on earth in a sustainable manner taking into account local environments and the affects of food production on said environments.[67]

Before colonization Indigenous Nations across Turtle Island were thriving civilizations[68] with complex societies and differing customs.[69][70][71]

In fact without the aid of The Wampanoag Nation some of the first settlers would not have been able to survive the winters and would have either starved or froze to death. The Wampanoag had a deep relationship with the land and the creatures they shared it with:

“We have lived with this land for thousands of generations—fishing in the waters, planting and harvesting crops, hunting the four-legged and winged beings and giving respect and thanks for each and every thing taken for our use. We were originally taught to use many resources, remembering to use them with care, respect, and with a mind towards preserving some for the seven generations of unborn, and not to waste anything.”[72]

There were many types of agriculture, means to sustenance and land management techniques across the so called Americas.[73][74] A common myth is that Indigenous Nations were barely surviving before European colonization and that Indigenous Nations lived within an untouched undisturbed landscape [75], but this is not accurate:

... “everyone would help themselves, eat when you are hungry, [there was] always food for everyone, and the fires never went out, the coals were always kept going… food was communal with a preference for the youth and elderly to eat first.” ...

“we need to get rid of this idea that we were barely getting by and starving. We had vast food reserves and never went hungry – there was much abundance.”[76]

Indigenous techniques of agriculture are typically rooted in a deep sense of place and understanding of the local environment- These techniques/considerations offer much guidance and a framework to transition away from the industrial agricultural system dominating the Earth today.[77] Before European colonization many Indigenous Nations were already practicing sustainable regenerative agriculture, which have influenced many sustainable agriculture techniques in the status quo (agroecology/permaculture.) [78] The reality of advanced agriculture techniques flies in the face of the myth of settlers reaching a pristine untouched land; Indigenous Nations had been stewards over Turtle Island since time immemorial.

Indigenous Nations practiced regenerative agriculture in part to ensure that soils would be capable of continued food production for the future Seven Generations, but also because of a sense of responsibility/stewardship for the environment, which is in stark contrast of European conceptions of the world which revolve around domination and 'taming of the wild.'

Forced Food Insecurity

First Nations and Indigenous Communities across Turtle Island suffer from food insecurity. In so-called Canada, 48% of First Nation Households[79] have difficulty putting enough food on the table. In the so-called U.S., 1 in 4 Native households are food insecure.[80] In so-called Mexico, 28 million people suffer from food insecurity, and 2.9 million of these persons are from largely Indigenous municipalities.[81] Worldwide, 795 million people suffer from hunger and food insecurity.[82]

Government policies encouraging settler colonialism in addition to land theft/ not honoring treaties decimated traditional food pathways Indigenous Nations had forged for millennia before the arrival of European settlers.[83] Continued land theft and forced removal from their homelands onto foreign reservations further deepened Indigenous Nation's food insecurity and dependence upon food from the United States government (food described as not fit for soldiers by the United States.)

In this process of colonialism, and later marginalization, indigenous nations become peripheral to the colonial economy and eventually are involved in a set of relations characterized by dependency. As Latin American scholar Theotono Dos Santos notes: "By dependence we mean a situation in which the economy of certain countries is conditioned by the development and expansion of another economy to which the former is subjected.' These circumstances-and indeed, the forced underdevelopment of sustainable indigenous economic systems for the purpose of colonial exploitation of land and resources-are an essential backdrop for any discussion of existing environmental circumstances in the North American community and of any discussion of sustainable development in a North American context. Perhaps most alarming is the understanding that even today this process continues, because a vast portion of the remaining natural resources on the North American continent are still under native lands or, as in the case of the disposal of toxic wastes on Indian reservations, the residual structures of colonialism make native communities focal points for dumping the excrement of industrial society.[84]

The United States Federal Government provides food rations to many Nations, because of previous agreements/ treaties. The food rations are typically unhealthy and have no relationship with traditional foods: "Diabetes was rare among Native peoples before the 1940s (the Navajo language had no word for diabetes prior to European arrival, for example) but exploded in the wake of commodity distribution, strongly contributing to the obesity and diabetes epidemics that Native communities are currently fighting."[85]

1887 Dawes Act

Food insecurity among Tribal communities today cannot be divorced from their land history, as federal policy promoted settler-colonialism and land theft, which disrupted Tribal communities’ food systems. One pivotal law is the 1887 Dawes Act, under which the U.S. government appropriated — effectively stole — collectively held Native land and then parceled it back to individual Native people (“allottees”). Typically 40, 80, or 160 acres in area, these parcels were held in trust by the federal government on behalf of allotees for 25 years, during which they were not subject to taxation. Allotees could manage the land but could not lease or sell it without government consent. Under the Dawes Act, after 25 years elapsed, allotees would own the land “fee simple,” meaning they would have full ownership and the ability to develop and manage the land as they wished. The land would also become subject to taxation at this time.

This policy was conceived of as a “civilizing” boon to Indian Country. Native peoples would engage in land ownership patterns like white Americans. They would enter the mainstream economy and become “self-sufficient,” by Euro-American standards. They would shift from traditional agricultural practices, adopting Euro-American planting methods and cultivating cash crops for sale. By assimilating into the dominant culture, proponents of the policy argued, Native peoples could secure their futures.[86]

Subsequent government policies continued to chip away at native lands- From the 1880s to 1934, allotment policy transferred 90 million acres of land from Native to non-Native ownership- the size of Montana. Through these policies food sovereignty for Native Nations is near impossible, because much Native land is controlled by the United States Federal Government and usage of the land must be approved by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA.) This has resulted in dependency upon government rations and is a continuation of the same genocidal tactics used in the past by the United States government.

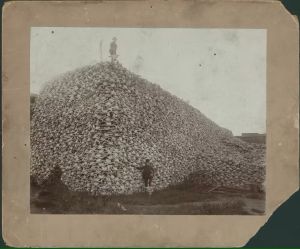

Buffalo Genocide

It all started in the 19th century when herds of 4 million American bison lived in the Great Plains and provided significant resources for the people that thrived there – such as food, medicine, clothing, shelter, tools, utensils, decoration and playthings. The buffalo was so valuable that the people of the Great Sioux called themselves Pte Oyate (Buffalo Nation) and stories of creation emerged detailing the buffalo using its nose to create a human from a pile of mud.[87]

North American Buffalo populations are estimated to have been in the 30-50 millions before European contact.[88] Generals William T. Sherman and Philip Sheridan spearheaded the military tactic of en masse slaughter of the buffalo in an attempt to "civilize" Indigenous Nations across the plains: "On 26 June 1869, the prestigious Army-Navy Journal reported that 'General Sherman remarked, in conversation the other day, that the quickest way to compel the Indians to settle down to civilized life was to send ten regiments of soldiers to the plains, with orders to shoot buffaloes until they became too scarce to support the redskins.'"[89]

Soon, it became the norm for Sherman and Sheridan to provide opportunities for the rich and influential to travel West and hunt Buffalo with U.S. Cavalry guns alongside prominent generals like General William F. Cody (Buffalo Bill Cody), who claimed to kill 4,000 Buffalo himself. "In fact, the Springfield army rifle was initially the favorite weapon of the hide hunters. The party killed over six hundred Buffalo on the hunt, keeping only the tongues and the choice cuts, but leaving the rest of the carcasses to rot on the plains."[90]

In a fifty-five-year period, 1830-1885, soldiers, hunters, and settlers killed more than 40 million Buffalo.

For millennia to follow, the tribes moved wherever the buffalo migrated. People among the tribes were well fed and no one ever got sick. That was until the Europeans colonized the Lakota territory and destroyed the culture that surrounded the buffalo. The mercenaries slaughtered millions of buffalo and the self-sufficient nature of the tribes ceased .After several years, the people were introduced to processed and canned carbohydrates, fats, salts, sugars, and preservatives. “Our warriorhood was lost when we accepted the food”. And, not only was the warriorhood lost, but public health issues began to arise such as heart disease, high blood pressure, obesity – and they still remain today.[91]

The genocide of the Buffalo completely ruptured the means to sustenance of the Oceti Sakowin, and altered their way of life permanently. The decimation of the buffalo is only but one example of the ways the United States government plotted and executed plans to disrupt Indigenous Nations sustainable symbiotic relationship with the land and all creatures they shared it with.[92]

Hua Parakore

Hua parakore is a kaupapa Māori (Indigenous) system and framework for growing kai (product and food) developed by Te Waka Kai Ora (National Maori Organics Authority).[93]

... with the Hua Parakore we're actually about building communities, and building communities which are resilient, which are transformational. And so when this farm received its full Hua Parakore verficiation we had a hui [gathering] of about 60 to 70 people up here. It was really kind of almost gaining collective consent. You know, we walked around the farm, we had people from the Maori organics group with us who asked questions in relation to the kaupapa [values.] Then we had other Maori people there steeped in matauranga Maori [Maori knowledge] and te reo [maori language] who were also, too, asking us questions. And so in lots of ways it's a learning framework, we get to ask these questions and we get to respond but then other people who have come to that hui, or that final verification, get to add their whakaaro, or their thoughts as well. It takes a full three years to become Hua Parakore verified and it's a community process, you know, we're bringing people along with us, we're strengthening our own knowledge systems, we're building our own ways and understandings of how to be growers within our own cultural practices, to tell our own kaupapa Maori [Maori values] stories in Aotearoa.[94]

Pine Ridge Reservation

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uZk8j1Lhi6I

Inter-National Food Sovereignty Movements

In response to neoliberal globalization a large diverse network of Inter-National Food Sovereignty Movements has emerged:

Diverse peasant, fisherfolk, indigenous and pastoralist associations have risen up to enact and demand food sovereignty: ‘the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems’. Food sovereignty calls for the food system, currently dominated by large corporations and international trade organizations, to be placed under the control of small- scale producers, gatherers and consumers. It also calls for modes of production that neither despoil nor enclose land from which rural peoples live. In developing the idea of food sovereignty, diverse activists have created, from different and potentially conflicting worldviews and interests, a convergent politics aimed at autonomy, democratic control, and social and ecological justice.

From an initial ‘social base in the peasantry of the Global South and the small-scale, family farm sector of the Global North’, food sovereignty has spread far and wide , informing and being informed by activists around the world including indigenous, pastoralist, fisherfolk and environmental movements, the World March of Women, and consumer and migrant agricultural worker movements in the United States and in Europe. Food sovereignty is now entering mainstream discourse, offering a rival to the common sense according to which mass production and industrial agriculture is key to feeding the world.

... The growth of the food sovereignty movement, the convergence of feminist, environmentalist, peasant, pastoralist, indigenous and fisherfolk movements on food sovereignty, and food sovereignty’s challenge to and transformation of global discourses suggests that activists are forming a counter-hegemonic movement, challenging and providing an alternative to a common sense of mass production and trade. Whilst the hegemony of a market-based, agro-industry dominated food system remains, a rival is emerging.[95]

Pluriversality

Horizontal VS Vertical Organizing

Urban & Rural Food Sovereignty

Proponents of industrial agriculture argue that high intensive chemical input farming is necessary to produce enough food for people living in large cities. This argument ignores that much food produced by industrial agriculture is not used to feed people, but cattle, and other purposes such as biofuels.[96] Beyond industrial food crop's destinations a complete reworking of urban planning and how we produce food in favor of a food sovereignty/ agroecology framework would take large cities into account and would be apt in adapting to feeding large population centers locally.[97] Clearly, this is not a transition that would happen over night, nor should it be taken lightly, but by shrugging off the entire idea in favor of a system that barely functions in the status quo is severely limiting to new visions and possibilities of reworking the food system we have today.

Within an agroecological framework a complete rethinking of rural and urban relations would be integral to ensuring a just transition is achieved[98]. As the whole point of a food sovereignty framework is to provide healthy sustainable food to the masses a just transition is tantamount; This means involving rural/ agrarian farmers in city planning and decision making will be important in achieving food sovereignty as a whole and aiding in the transition away from industrial food crops.

Solely focusing on a reworking of the urban/ rural relationship would not be sufficient, and a broader radical transition away from capitalist market-relations/ neoliberalism would be necessary to prevent the reproduction of relationships that are already occurring in the status quo and are contributing to food insecurity and farmer displacement:

...the radical transformations needed to bring forward agroecological transitions not only need to build alternatives that support agroecological farmers and communities, but also to actively dismantle disempowering and oppressive processes, disabling arrangements and unjust systems. If we look at the urbanism side of these processes, this means not only creating isolated, ad-hoc progressive initiatives... but to systematically break speculative land markets, halt the logics of substitution that are at the roots of the commodification of food, place urban soil care centrally within land policies, nourish the commoning of urban resources in ways that allow communities to exercise control of their social reproduction, and more generally enable the full politicization of biopolitical relations across the spectrum, moving away from technical and functionalist approaches solely focussed on food. [99]

Traditional Ecological Knowledge will be a necessary epistemological lens to adopt alongside the aforementioned frameworks and methods of agriculture production.

Fruit Trees

Planting food crops such as fruit trees should be part of urban planning and should be implemented in most cities with consideration for what type of fruit trees grow best in the region. Fruit trees especially in an urban setting have multiple benefits including easy access to fresh healthy food, potential education about growing food, and a gained sense of stewardship for the environment.[100]

Growing fruit trees in densely populated urban environments can also serve as a method of blurring the lines between urban and rural populations. Fruit trees have the potential to be a major source of nourishment for large populations enhancing food security and sovereignty by supplementing food stock reserves, which should be established in all major metropolitan areas with locally produced food. Utilizing fruit trees shows how food can be grown in urban environments and not just rural areas exposing how capitalist market-relations have created fissures between these two populations putting them at odds with one another to the detriment of both.[101]

Klinic Garden

The Klinic Garden is a permaculture 'U-Pick' community garden in Winnipeg, Manitoba in so called Canada. The garden is led by Audrey Logan (many people call her ‘Auntie,') and she emphasizes a return to Indigenous place based gardening. The garden is open to the general public to pick any food or medicine freely; Auntie holds group gardening days typically once a week during the growing season, which allows the general public to learn about Indigenous permaculture while contributing to the garden- in this way the garden also serves as a knowledge commons.

Her teachings emphasize that many plants the general public consider weeds have medicinal value (for example thistle is good for liver cleansing, but is often considered a weed.) "Blood Knowledge" is another concept Auntie discusses through her teachings; Blood Knowledge is knowledge passed down to children through their mothers in the womb. Auntie emphasizes that everyone has knowledge about the Earth, plants, and ecology, but it has to be tapped into through experience.

Community Gardens

There are large disparities in access to healthy and affordable food depending upon one's race where one lives and how much money is made.[102] "...There is significant variation in food access across neighborhood types tied to larger systems; namely spatial racism and discrimination, creating barriers to healthy eating for lower-income residents and people living in predominantly African American neighborhoods."[103] Access to healthy and nutritious food should never be restricted and should be readily available. Community gardens are an excellent way to bridge this gap and aid in the transition away from industrial agriculture, which unevenly distributes food.[104] [105] Growing community gardens, fruit trees, backyard gardens, food grown on decks etc will create a mosaic of food stores everywhere. Combine these food sources with traditional Indigenous techniques of food preservation such as dehydrating foods and neighborhoods will be capable of creating their own caches filled with nutritious locally grown food.

Restricted vs Unrestricted Gardens

The Klinic Garden mentioned above is a great example of an unrestricted community garden. The food and medicines are freely available for anyone passing by and the knowledge transference that is available during the growing season is a demonstration of the active benefits that are readily available for community members when gardens are erected with knowledge and food being shared with one another.

Urban-Rural Rift

Capitalism and market-based relations/ production of food has created a dichotomy between so called urban and rural areas; Essentially pitting these two populations against one another. Rupturing this dichotomy and integrating the two populations together is a necessary step in establishing food sovereignty and particularly important during the transition away from capitalism:[106]

Abolition of the antithesis between town and country is not merely possible. It has become a direct necessity of industrial production itself, just as it has become a necessity of agricultural production and, besides, of public health. The present poisoning of the air, water and land can be put an end to only by the fusion of town and country; and only such fusion will change the situation of the masses now languishing in the towns, and enable their excrement to be used for the production of plants instead of for the production of disease. (Marx & Engels, 1978, p. 723)

In this same tradition, mending ecological rift via the recycling of organic waste is central to UA [Urban Agriculture] across the globe. This concept of returning nutrients to agricultural soils in the form of urban waste is vital to overcoming the “antithesis between town and country” and is fundamental to a “restitutive” agriculture. While few urban planners and mainstream development practitioners likely look towards Marx and Engels for inspiration, these obscure passages describing metabolic rift are particularly prescient, relevant not only to the development of sustainable agriculture, but also to urban waste management and the impending environmental crises of mega-urbanization. [107]

Counter-Sovereignty

The Washington Consensus

“The immediate objects are the total destruction and devastation of their settlements… It will be essential to ruin their crops now in the ground and prevent their planting more… Our future security will be in their inability to injure us, the distance to which they are driven, and in their terror.”

-Orders by U.S. General George Washington, planning war crimes against the Haudenosaunee in 1779 (La Duke 2005: 154)

"Control oil, you control nations; control food and you control the people."

-U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, 1974 (National Security Study Memorandum 200: Implications of Worldwide Population Growth for U.S. Security and Overseas Interest)

English Imperialism

Sources

- ↑ A. Haroon Akram-Lodhi, "Accelerating towards food sovereignty", Third World Quarterly, 2015 Vol. 36, No. 3, 563–583, https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2015.1002989

- ↑ International Planning Committee for Food Sovereignty, “Définition de la souveraineté alimentaire.”

- ↑ https://tcleadership.org/la-via-campesina/

- ↑ Dunford, R. (2020). Converging on food sovereignty: transnational peasant activism, pluriversality and counter-hegemony. Globalizations, 1–15. doi:10.1080/14747731.2020.17224

- ↑ https://www.zinnedproject.org/materials/food-farming-and-justice-a-role-play-on-la-via-campesina/

- ↑ https://climatejusticealliance.org/just-transition/

- ↑ Dr.Vandana Shiva, Who Really Feeds the World:The Failures of Agribusiness and the Promise of Agroecology, Page:127

- ↑ Dr.Vandana Shiva, Who Really Feeds the World:The Failures of Agribusiness and the Promise of Agroecology,Page:127

- ↑ Dr.Vandana Shiva, Who Really Feeds the World:The Failures of Agribusiness and the Promise of Agroecology,Page:128

- ↑ Dr.Vandana Shiva, Who Really Feeds the World:The Failures of Agribusiness and the Promise of Agroecology,Page:128

- ↑ Dr.Vandana Shiva, Who Really Feeds the World:The Failures of Agribusiness and the Promise of Agroecology,Page:128-129

- ↑ Dr.Vandana Shiva, Who Really Feeds the World:The Failures of Agribusiness and the Promise of Agroecology, Page: 129

- ↑ Dr.Vandana Shiva, Who Really Feeds the World:The Failures of Agribusiness and the Promise of Agroecology, Page: 130

- ↑ Dr.Vandana Shiva, Who Really Feeds the World:The Failures of Agribusiness and the Promise of Agroecology, Page: 131

- ↑ Dr.Vandana Shiva, Who Really Feeds the World:The Failures of Agribusiness and the Promise of Agroecology, Page: 131-132

- ↑ Dr.Vandana Shiva, Who Really Feeds the World:The Failures of Agribusiness and the Promise of Agroecology, Page: 132-133

- ↑ Daniel R Wildcat, Red Alert: Saving the Planet with Indigenous Knowledge, 2009, p. 48

- ↑ Daniel R Wildcat, Red Alert: Saving the Planet with Indigenous Knowledge, 2009, p. 54

- ↑ Shelef O, Weisberg PJ, Provenza FD. The Value of Native Plants and Local Production in an Era of Global Agriculture. Front Plant Sci. 2017 Dec 5;8:2069. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.02069. PMID: 29259614; PMCID: PMC5723411.

- ↑ http://www.uky.edu/~rsand1/china2017/library/NOTES/LaDuke%20-%20Traditional%20Ecological%20Knowledge%20-%20Notes.pdf

- ↑ http://www.nmfccc.ca/uploads/4/4/1/7/44170639/dehydration_nations_zine.pdf

- ↑ https://www.thecommonsjournal.org/article/10.5334/ijc.1043/

- ↑ https://wiki.p2pfoundation.net/Seed_Commons

- ↑ https://www.navdanya.org/bija-refelections/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/reclaim-the-seed-8th-april.pdf

- ↑ Dr.Vandana Shiva, Who Really Feeds the World?: The Failures of Agribusiness and the Promise of Agroecology, Page 79-80

- ↑ https://www.theguardian.com/news/2019/jan/28/can-we-ditch-intensive-farming-and-still-feed-the-world

- ↑ Martha Jane Robbins (2015) Exploring the ‘localisation’ dimension of food sovereignty, Third World Quarterly, 36:3, 449-468, DOI: 10.1080/01436597.2015.1024966

- ↑ Martha Jane Robbins (2015) Exploring the ‘localisation’ dimension of food sovereignty, Third World Quarterly, 36:3, 449-468, DOI: 10.1080/01436597.2015.1024966

- ↑ Martha Jane Robbins (2015) Exploring the ‘localisation’ dimension of food sovereignty, Third World Quarterly, 36:3, 449-468, DOI: 10.1080/01436597.2015.1024966

- ↑ Downey, G. (2011). Alienation and Food. Philologia, 3(1). DOI: http://doi.org/10.21061/ph.v3i1.100

- ↑ Dr.Vandana Shiva, Earth Democracy: Justice, Sustainability, and peace, Page 16

- ↑ https://wfpc.sanford.duke.edu/north-carolina/durham-food-history/the-plight-of-farmers-the-tools-of-dispossession-1900-1950/

- ↑ https://time.com/5736789/small-american-farmers-debt-crisis-extinction/

- ↑ Martha Jane Robbins (2015) Exploring the ‘localisation’ dimension of food sovereignty, Third World Quarterly, 36:3, 449-468, DOI: 10.1080/01436597.2015.1024966

- ↑ Graeber, D., & Wengrow, D. (2021). The dawn of everything: a new history of humanity. First American edition. New York, Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- ↑ Keeler, K. (2022). Before colonization (BC) and after decolonization (AD): The Early Anthropocene, the Biblical Fall, and relational pasts, presents, and futures. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, 5(3), 1341–1360. https://doi.org/10.1177/25148486211033087

- ↑ Hannah Wittman (2009): Reworking the metabolic rift: La Vía Campesina, agrarian citizenship, and food sovereignty, The Journal of Peasant Studies, 36:4, 805-826

- ↑ Wittman, H. (2009). Reworking the metabolic rift: La Vía Campesina, agrarian citizenship, and food sovereignty. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 36(4), 805–826.

- ↑ https://www.foodsystemprimer.org/food-production/industrialization-of-agriculture/

- ↑ https://www.nrdc.org/stories/industrial-agricultural-pollution-101

- ↑ Horrigan, L., Lawrence, R. S., & Walker, P. (2002). How sustainable agriculture can address the environmental and human health harms of industrial agriculture. Environmental Health Perspectives, 110(5), 445–456. doi:10.1289/ehp.02110445

- ↑ Jonathan Storkey, Toby J.A. Bruce, Vanessa E. McMillan, Paul Neve, Chapter 12 - The Future of Sustainable Crop Protection Relies on Increased Diversity of Cropping Systems and Landscapes, Editor(s): Gilles Lemaire, Paulo César De Faccio Carvalho, Scott Kronberg, Sylvie Recous, Agroecosystem Diversity, Academic Press, 2019, Pages 199-209, ISBN 9780128110508, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-811050-8.00012-1.

- ↑ Hannah Wittman (2009): Reworking the metabolic rift: La Vía Campesina, agrarian citizenship, and food sovereignty, The Journal of Peasant Studies, 36:4, 805-826

- ↑ https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/nov/03/big-agriculture-climate-crisis-cop27

- ↑ Salmón, E. (2000). Kincentric Ecology: Indigenous Perceptions of the Human-Nature Relationship. Ecological Applications, 10(5), 1327–1332. https://doi.org/10.2307/2641288

- ↑ https://www.soilassociation.org/causes-campaigns/a-ten-year-transition-to-agroecology/what-is-agroecology/

- ↑ Sociotechnical Context and Agroecological Transition for Smallholder Farms in Benin and Burkina Faso Parfait K. Tapsoba , Augustin K. N. Aoudji, Madeleine Kabore, Marie-Paule Kestemont, Christian Legay and Enoch G. Achigan-Dako

- ↑ https://www.organicwithoutboundaries.bio/2018/08/08/agroecological-farmers-rethink/

- ↑ Dr. Vandana Shiva, 'Who Really Feeds the World:The Failures of Agribusiness and the Promise of Agroecology Page:62

- ↑ https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/10-things-you-should-know-about-industrial-farming

- ↑ Botelho, M. I. V., Cardoso, I. M., & Otsuki, K. (2015). “I made a pact with God, with nature, and with myself”: exploring deep agroecology. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 40(2), 116–131. doi:10.1080/21683565.2015.11157

- ↑ Sociotechnical Context and Agroecological Transition for Smallholder Farms in Benin and Burkina Faso Parfait K. Tapsoba , Augustin K. N. Aoudji, Madeleine Kabore, Marie-Paule Kestemont, Christian Legay and Enoch G. Achigan-Dako

- ↑ ↑ Tapsoba, P.K.; Aoudji, A.K.N.; Kabore, M.; Kestemont, M.-P.; Legay, C.; Achigan-Dako, E.G. Sociotechnical Context and Agroecological Transition for Smallholder Farms in Benin and Burkina Faso. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1447. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy10091447

- ↑ https://www.globalagriculture.org/whats-new/news/en/34543.html

- ↑ https://www.ifad.org/en/crops

- ↑ https://www.fao.org/family-farming/detail/en/c/1398060/

- ↑ https://www.globalagriculture.org/whats-new/news/en/34543.html

- ↑ Dr. Vandana Shiva, 'Who Really Feeds the World:The Failures of Agribusiness and the Promise of Agroecology Page:56&60

- ↑ https://www.soilassociation.org/causes-campaigns/agroforestry/agroforestry-what-are-the-benefits/

- ↑ Nair, P.K.R. (2011), Agroforestry Systems and Environmental Quality: Introduction. J. Environ. Qual., 40: 784-790. https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2011.0076

- ↑ https://www.soilassociation.org/causes-campaigns/agroforestry/what-is-agroforestry/

- ↑ https://www.soilassociation.org/causes-campaigns/agroforestry/agroforestry-what-are-the-benefits/

- ↑ Zhu, X., Liu, W., Chen, J. et al. Reductions in water, soil and nutrient losses and pesticide pollution in agroforestry practices: a review of evidence and processes. Plant Soil 453, 45–86 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-019-04377-3

- ↑ Nair, P.K.R. (2011), Agroforestry Systems and Environmental Quality: Introduction. J. Environ. Qual., 40: 784-790. https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2011.0076

- ↑ Zhu, X., Liu, W., Chen, J. et al. Reductions in water, soil and nutrient losses and pesticide pollution in agroforestry practices: a review of evidence and processes. Plant Soil 453, 45–86 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-019-04377-3

- ↑ https://nfu.org/2020/10/12/the-indigenous-origins-of-regenerative-agriculture/

- ↑ Bethany Elliott, Deepthi Jayatilaka, Contessa Brown, Leslie Varley, Kitty K. Corbett, "“We Are Not Being Heard”: Aboriginal Perspectives on Traditional Foods Access and Food Security", Journal of Environmental and Public Health, vol. 2012, Article ID 130945, 9 pages, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/130945

- ↑ https://fncaringsociety.com/sites/default/files/Indigenous%20Contributions%20to%20North%20America%20and%20the%20World.pdf

- ↑ Clement, R. M., & Horn, S. P. (2001). Pre-Columbian land-use history in Costa Rica: a 3000-year record of forest clearance, agriculture and fires from Laguna Zoncho. The Holocene, 11(4), 419–426.

- ↑ Graeber, D., & Wengrow, D. (2021). The dawn of everything: a new history of humanity. First American edition. New York, Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- ↑ Keeler, K. (2022). Before colonization (BC) and after decolonization (AD): The Early Anthropocene, the Biblical Fall, and relational pasts, presents, and futures. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, 5(3), 1341–1360. https://doi.org/10.1177/25148486211033087

- ↑ https://www.nlm.nih.gov/nativevoices/timeline/200.html

- ↑ https://nfu.org/2020/10/12/the-indigenous-origins-of-regenerative-agriculture/

- ↑ https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/the-historical-determinants-of-food-insecurity-in-native-communities

- ↑ https://jan.ucc.nau.edu/~alcoze/for398/class/pristinemyth.html

- ↑ https://branchoutnow.org/growing-sovereignty-turtle-island-and-the-future-of-food/#comments

- ↑ Bethany Elliott, Deepthi Jayatilaka, Contessa Brown, Leslie Varley, Kitty K. Corbett, "“We Are Not Being Heard”: Aboriginal Perspectives on Traditional Foods Access and Food Security", Journal of Environmental and Public Health, vol. 2012, Article ID 130945, 9 pages, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/130945

- ↑ https://nfu.org/2020/10/12/the-indigenous-origins-of-regenerative-agriculture/

- ↑ https://globalnews.ca/news/6136161/first-nations-food-insecurity-study/

- ↑ https://www.firstnations.org/wp-content/uploads/publication-attachments/8%20Fact%20Sheet%20Food%20Deserts%2C%20Food%20Insecurity%20and%20Poverty%20in%20Native%20Communities%20FNDI.pdf

- ↑ https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/10/2/473/htm

- ↑ https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/10/2/473/htm

- ↑ https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/the-historical-determinants-of-food-insecurity-in-native-communities

- ↑ http://www.uky.edu/~rsand1/china2017/library/NOTES/LaDuke%20-%20Traditional%20Ecological%20Knowledge%20-%20Notes.pdf

- ↑ https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/the-historical-determinants-of-food-insecurity-in-native-communities

- ↑ https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/the-historical-determinants-of-food-insecurity-in-native-communities

- ↑ https://www.cwis.org/2020/07/buffalo-are-the-backbone-of-lakota-food-sovereignty/

- ↑ Dunbar-Ortiz, R. (2015). An indigenous peoples' history of the United States. Boston, Beacon Press.

- ↑ https://blog.nativehope.org/how-the-destruction-of-the-buffalo-impacted-native-americans

- ↑ https://blog.nativehope.org/how-the-destruction-of-the-buffalo-impacted-native-americans

- ↑ https://www.cwis.org/2020/07/buffalo-are-the-backbone-of-lakota-food-sovereignty/

- ↑ https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2016/05/the-buffalo-killers/482349/

- ↑ https://jessicahutchings.org/what-is-hua-parakore/

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x3qMIFQLK8c

- ↑ Dunford, R. (2020). Converging on food sovereignty: transnational peasant activism, pluriversality and counter-hegemony. Globalizations, 1–15. doi:10.1080/14747731.2020.17224

- ↑ https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/10-things-you-should-know-about-industrial-farming

- ↑ Ebenso B, Otu A, Giusti A, Cousin P, Adetimirin V, Razafindralambo H, Effa E, Gkisakis V, Thiare O, Levavasseur V, Kouhounde S, Adeoti K, Rahim A, Mounir M. Nature-Based One Health Approaches to Urban Agriculture Can Deliver Food and Nutrition Security. Front Nutr. 2022 Mar 11;9:773746. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.773746. PMID: 35360699; PMCID: PMC8963785.

- ↑ LERNER, A. M., & EAKIN, H. (2011). An obsolete dichotomy? Rethinking the rural-urban interface in terms of food security and production in the global south. The Geographical Journal, 177(4), 311–320. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41475774

- ↑ Chiara Tornaghi & Michiel Dehaene (2020) The prefigurative power of urban political agroecology: rethinking the urbanisms of agroecological transitions for food system transformation, Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 44:5, 594-610, DOI: 10.1080/21683565.2019.1680593

- ↑ Juliette Colinas, Paula Bush, Kevin Manaugh, The socio-environmental impacts of public urban fruit trees: A Montreal case-study, Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, Volume 45, 2019, 126132, ISSN 1618-8667, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2018.05.002.

- ↑ McClintock, Nathan, "Why Farm the City? Theorizing Urban Agriculture through a Lens of Metabolic Rift" (2010). Urban Studies and Planning Faculty Publications and Presentations. 91. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/usp_fac/91

- ↑ Moore LV, Diez Roux AV, Nettleton JA, Jacobs DR Jr. Associations of the local food environment with diet quality--a comparison of assessments based on surveys and geographic information systems: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Am J Epidemiol. 2008 Apr 15;167(8):917-24. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm394. Epub 2008 Feb 27. PMID: 18304960; PMCID: PMC2587217.

- ↑ Colson-Fearon B, Versey HS. Urban Agriculture as a Means to Food Sovereignty? A Case Study of Baltimore City Residents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Oct 5;19(19):12752. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191912752. PMID: 36232052; PMCID: PMC9566707.

- ↑ Elmes, M. B. (2018). Economic Inequality, Food Insecurity, and the Erosion of Equality of Capabilities in the United States. Business & Society, 57(6), 1045–1074. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650316676238

- ↑ Ebenso B, Otu A, Giusti A, Cousin P, Adetimirin V, Razafindralambo H, Effa E, Gkisakis V, Thiare O, Levavasseur V, Kouhounde S, Adeoti K, Rahim A, Mounir M. Nature-Based One Health Approaches to Urban Agriculture Can Deliver Food and Nutrition Security. Front Nutr. 2022 Mar 11;9:773746. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.773746. PMID: 35360699; PMCID: PMC8963785.

- ↑ McClintock, Nathan, "Why Farm the City? Theorizing Urban Agriculture through a Lens of Metabolic Rift" (2010). Urban Studies and Planning Faculty Publications and Presentations. 91. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/usp_fac/91

- ↑ McClintock, Nathan, "Why Farm the City? Theorizing Urban Agriculture through a Lens of Metabolic Rift" (2010). Urban Studies and Planning Faculty Publications and Presentations. 91. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/usp_fac/91